Kent Hehr is in his campaign office on a sweltering May Saturday, getting ready to go door knocking. Hehr is the federal Liberal candidate for Calgary-Centre, currently held by Conservative Joan Crockatt. The election is five months away but Hehr and his campaign team are busy.

“This is starting to be an exercise in futility,” says Vincent St. Pierre, Hehr’s executive assistant. St. Pierre is kneeling on the floor, trying to replace the batteries on Hehr’s wheelchair, stuffing them into the undercarriage after cutting off their oversized plastic handles with a butter knife. Changing the batteries is usually a 20-minute process, but today it’s taken almost an hour.

Hehr’s partner, Deanna, hands the candidate a slice of pizza and refills his travel mug with water. She tells St. Pierre to abandon the new batteries and put in the old ones. He does, but they won’t connect.

The stress in the room is palpable. Hehr closes his eyes and rests his hands on his chest. He’s gone into a meditative state, a slight grin on his face. In the midst of the fight with the battery, in a hot office thick with the smell of pepperoni, it’s an act of impressive grace.

What Kent Hehr is trying to do in Calgary-Centre is make history. No federal Liberal has won a seat in Calgary since Pat Mahoney did in 1968, the year Trudeaumania swept the nation. Since then, for nearly five decades, Calgary has been a stout, exclusively conservative bastion—but Hehr thinks he can break through those walls. In 2008 and 2012 he ran successfully for the provincial Liberals in Calgary-Buffalo, which lies within the federal riding of Calgary-Centre. Whether or not there’s a national mania for another Trudeau (Justin), Hehr is a strong candidate. Early polls have him as the favourite.

No federal Liberal has won a seat in Calgary since Pat Mahoney did in 1968, the year Trudeaumania swept the nation.

The battery problem solved, Hehr and five volunteers arrive in prosperous Scarboro, a place that looks a bit like Hobbiton if owned by investment bankers. Each volunteer takes a handful of brochures and prepares to track voter data on tablets. Communications lead Jody MacPherson will take photos of voters in conversation with the candidate for use on social media (with voters’ consent). As the gang heads out, Hehr gives the volunteers their opening lines (“Hi, I’m volunteering for Kent Hehr…”), too quickly for anyone to memorize. He doesn’t seem concerned; just eager to get territory covered before his wheelchair runs out of juice.

Their starting point is near where Hehr’s old provincial turf borders new territory. Facing up the hill, he says, “It’s not that different. Wealth isn’t always the determinant of how someone votes.”

This is an important matter for Hehr as he campaigns because, though his old riding of Calgary-Buffalo lies within Calgary-Centre, the parts of the federal riding that are outside his old provincial constituency are significantly wealthier. Such neighbourhoods include Scarboro, Elbow Park, Britannia, Bel-Aire and Mount Royal, some of Calgary’s most well-heeled addresses. The 2011 National Household Survey shows Calgary-Centre to have an average family income of $171,228 compared to Calgary-Buffalo at $106,609.

Wealth might not be the only determining factor in how someone votes, but the fact is that Hehr is taking his federal campaign into territory with different lifestyles and concerns than he was used to in provincial politics. Some of the issues he and his party are advocating in 2015—a new federal health accord, the first since 2004, and added funding for the Canada Pension Plan—are appealing to riding residents. Others are a harder sell. For example, Hehr is floating the concept of a guaranteed annual income, an idea “whose time has come,” he says. The Liberals would also jettison the Harper government’s income splitting policy, which benefits many affluent families.

Hehr often says the “bread and butter” of being a politician is talking to people. His speech is considered and cadenced, and it speeds up when something catches his interest. At one of the doors, a septuagenarian tells Hehr he likes him but it’s just too bad he’s a Liberal. Hehr replies that early media buzz says he’ll probably be in Ottawa come October: “That and a buck-fifty might get me a cup of coffee.” He adds that the gentleman should visit him in Ottawa if he wins. As Hehr jets to the next house on the block, he says, “He likes me but he’s not gonna vote for me. It’s like they say in multilevel marketing: Some will, some won’t, so what.”

When Hehr is not door-knocking, he often travels the public areas of his riding. After nine years in provincial politics, he is a fixture. People might find him chatting outside the crowded Ship and Anchor pub on busy 17th Avenue or visiting with grocery shoppers in Co-op or Safeway. At his main watering hole, The Blind Monk on 12th Avenue, Hehr enjoys debating his conservative buddies, the “ol’ Kool-Aid drinkers,” as he calls them.

“Have some beers and swap some lies. It’s not the worst thing in the world,” he says.

Earlier in May, Hehr paid a visit to a Grade 3 class in Varsity Acres, in northwest Calgary, far outside his riding. “All political parties believe in building roads,” he told the slightly mystified children. “After that, we run into some differences.” Hehr was talking to the students about democracy and community, but digressed to some of the secrets of political popularity. “You’re successful in politics if you get 37 to 38 per cent of the vote.” This drew confused looks from the kids. “We Liberals haven’t been in power in Alberta for 94 years, so you can’t blame us for anything.”

Naturally, the Varsity Acres kids got around to asking why he was in a wheelchair. Hehr did not tell them he had been shot. He said only that he had a spinal cord injury and it was a “traumatic experience.” He described how, at age 21, he found himself paralyzed and in the hospital for nine months. He lived on Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) for nine years. Eventually, he went to law school and became a politician. “People have a right to be curious,” he said as we left the school. “I rarely ever think about the night I was shot, or the person who shot me.”

Hehr’s father Richard’s memories of that night are vivid. His son was out with friends along Calgary’s notorious downtown party strip, Electric Avenue. At 3:30 a.m., on October 3, 1991, there was a knock on Richard’s door. He remembers the moment this way: “A policeman tells you your son is in the hospital. He was shot in the neck.” A random act of violence. In the hospital, the first thing Hehr said to his parents was, “Mom and dad, I’m paralyzed and I wish I was dead.”

Later, after tests confirmed his condition—he would live but likely remain paralyzed—Hehr told his parents, “I guess we better get on with it.”

Hehr is described medically as a C5 quadriplegic. He can feel his upper chest and above, and has no difficulty breathing. He has the use of his biceps but not his triceps, and retains most of the use of his hands.

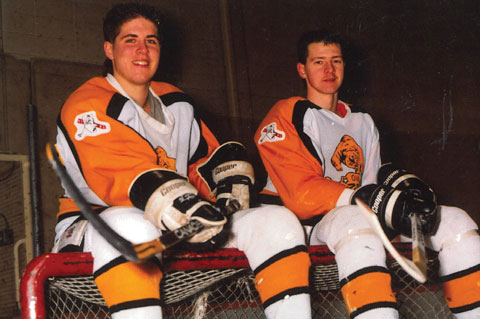

Young Kent Hehr was a “brash, cocky, outgoing and smart” hockey player. (Kent Hehr)

“You lose a sense of yourself when it happens,” he says. “At the time, I worked at Safeway, was on the college hockey team, went to classes. All of a sudden I’m asking, ‘Who am I?’ It took me 10 years to feel comfortable in my skin again.”

The portrait that emerges of Hehr before the shooting is of an opinionated and gifted hockey player who liked to drink beer and chase women.

“I often rebelled against authority, whether coaches or in the classroom,” he says. As a Triple-A Midget defenceman, Hehr had a reputation for being difficult. After getting bumped from the Lloydminster Bobcats, he called up Don Phelps, who was then coach of the Calgary Canucks, looking for a roster spot.

Phelps remembers him well. “He was brash, cocky, outgoing and smart. Kent pushed boundaries but he knew what he could get away with. He was smart enough to pick his battles wisely. I was glad I brought him on the team. He was a skilled defenceman and my best player.”

The transition after the shooting was harsh. “I got old when I was young,” Hehr says. “It was very important to me to put on a brave face, to move forward. It was difficult, but projecting that became a way of living.” The most difficult moment was returning to his studies at the University of Calgary. “I used to manage those halls as a hockey player. Now I had to do it as a C5 quadriplegic.”

Hehr says he owes much of his success to his sister, Kristie Smith, who helped him adjust to his new life. This took a large personal toll on her. “She was under a huge amount of stress and ended up flunking out of school,” he says. But her encouragement got him back to university after he’d spent nearly a year in hospital. Her pursuit of a law degree inspired Hehr to follow suit. She currently practises pipeline law with TransCanada.

After completing his law degree at the University of Calgary in 2001, Hehr spent seven years at Fraser Milner Casgrain. The firm’s offices were located in his future riding of Calgary-Buffalo. Though he says he was an “average” lawyer, he enjoyed practising law, and it gave him invaluable skills in building and dissecting arguments regarding legislation.

The aid Hehr received from the healthcare system and AISH were essential to his recovery and career progress. This fuelled in him a desire to protect and improve the resources that were available to people with disabilities. He became involved with community organizations including the United Way and the Canadian Paraplegic Association. “That crystallized for me that I wanted to get into politics,” he says.

Five or six years after the shooting, police told Hehr they had arrested someone who, as part of a plea deal, could name the person who’d shot him. By then he felt he had started to move on with his life, and the revelation brought little relief. “The trial dragged all of that up again,” he says. “I understand why women who are victims of rape sometimes don’t want a trial. My life wasn’t going to change one iota whether they jailed someone or not.”

While he was an MLA, Hehr raised at least one disability issue in the Legislature each year. But he also made a conscious decision not to dwell on disability in the House. “I think if I went at it ad nauseam, it would turn people off,” he says. “What I love most is being able to share my life with the public. I relish that. I was always the kid in the elevator who wanted to talk to that other person.”

On May 21, Kent Hehr turns the opening of his campaign office into a festive occasion. The room is packed with long-time supporters and newbies, and Hehr could not be happier. He rockets around the room, shaking hands and directing staff and never seeming to forget a face or a name. He asks the crowd to be quiet and to gather around him. When he has their attention, he lowers his voice. “At the end of the day, we’re gonna win,” he tells them. He wants to go to Ottawa to show that Calgary isn’t the conservative “wasteland” it’s purported to be. Ironically, this comment comes two weeks after Rachel Notley’s provincial election win. He jokes: “She [Notley] may have done that for me.”

Hehr’s love of politics goes back to his family. Political discussions were a regular feature of family chat. Hehr says that as a kid he “openly identified as a Liberal,” the voting preference of his parents. The basis of his belief was that liberalism meant everyone, whether rich or poor, should have equal opportunity. “Growing up, I never missed a meal and my parents got me involved in everything,” says Hehr. “I assumed everyone had it similar to me.”

He began to lean toward provincial politics during his years as a working lawyer. “I’ve always believed that government matters, and I didn’t think the PCs had governed well since 1993.” Hehr struck up a friendship with Alberta Liberal leader Kevin Taft, who asked him to run for the party in Calgary-Buffalo. Hehr accepted and won the nomination in 2006. As for his chances in the ensuing 2008 election race, he says he wasn’t that concerned. “I thought the worst that can happen is I return to law. Now politics is my life.”

Hehr is discussing his federal chances, two weeks after the NDP’s provincial win. He jokes: “[Notley] may have done that for me.”

Looking back, Taft says Hehr’s combination of life experience and legal training made him stand out, as well as his fearlessness in confronting controversial issues. “In the Legislature he was an absolute champion of public education and healthcare,” Taft says. “He knows his principles and he stands by them.”

Naturally, the two men spent time campaigning together. “People connect with Kent instantly,” Taft says. “When you mainstreet with Kent or go campaigning in his neighbourhoods, it’s like being in a moving festival. There’s noise, people, laughter, crowds. Kent loves people and people love Kent. But what I saw in Kent as I spent more time with him behind the scenes was the man behind the image. When you watch him in different settings over a period of months and years, you realize he has outsized fortitude and courage. People say that still waters run deep; in Kent’s case, flowing waters run deep too.”

Hehr cites several achievements in his seven years as MLA for Calgary-Buffalo. As justice critic, he pressured the government to increase police presence in downtown Calgary to tackle gun violence. He is proud of the day-to-day work he did as an MLA, hearing the concerns of homeless constituents and helping low-income seniors acquire hearing aids and dental surgery. Hehr says he began to argue long before anyone else did that Alberta’s fiscal problems weren’t about high expenses but about low revenue. He lists his 2014 legislative motion in support of Gay–Straight Alliances as among his proudest moments. “It was good public policy, helping LGBTQ youth,” he says. Even the Tories couldn’t ignore it forever. He also believes the Wildrose refusal to back the eventual bill to support GSAs was one of the key factors that kept them from winning the 2015 election.

With federal Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, 2013. (Kent Hehr)

But being in the Liberal opposition for seven years, vastly outnumbered by the PC majority, inevitably wore on him. Hehr says it was not anything in particular that made him choose to move on to federal politics, but that the time was right for a “career transition.”

“Alberta is a very progressive place,” says Hehr. “I feel it in every fibre of my being.” The provincial NDP’s victory in May does suggest that Alberta is ripe for change. It helps Hehr that Calgary-Centre’s MP, Joan Crockatt, who is running for re-election, won less than convincingly in the 2012 by-election (37 per cent of the popular vote) and has not shone in Parliament.

In the run-up to October’s federal election, Hehr may have recent history on his side. Crockatt won the by-election because of a vote-split on the left, with the Liberal candidate, Harvey Locke, receiving 33 per cent of the vote. Calgary Ward 8 councillor Evan Woolley sees the opposition vote in Calgary-Centre “naturally” going to Hehr this time. “Calgarians are shedding that conservative skin,” says Woolley. “You can still be progressive, centrist, but not necessarily a left-winger.” Woolley sees in Hehr the kind of populist appeal that Ralph Klein enjoyed: the ability to chat with anyone; the kind of guy you would like to have a beer with.

Author Chris Turner, who garnered nearly 26 per cent of the 2012 Calgary-Centre vote as the Green Party candidate, also likes Hehr’s chances. “I think the thing we demonstrated in 2012 was that people were willing to vote for someone other than a Conservative. …Kent has proven to be a spectacularly talented retail politician—a guy who gets to know everyone in his riding and goes to lots of events. He’s a hard-working MLA. When people are voting, they’re not voting for a Liberal candidate per se, they’re voting for him.”

One of Kent Hehr’s occasional sideline gigs is officiating at weddings. On another brilliant day in May, he greets a bride and groom at Calgary’s Canada Olympic Park. He opens the service by saying, “I’m not a preacher or a rabbi, merely an unemployed politician. There’s a lot of them in Alberta these days.”

Bryn Evans is a journalist and arts critic based in Calgary. He was a long-time writer and editor for Fast Forward Weekly.