The memoir, by its nature, is a story about becoming, an account of how someone starts in one place and ends up in another. It is a form that seems to emerge from some deep-seated impulse. As Edmonton’s Adriana Davies puts it, “It would seem that the act of remembering is essential to the human condition.”

The problem of writing a memoir is space: the knowledge that if you squander words on one subject, you are going to have to skimp on another. And, obviously, the more accomplishments there are to be reported, the harder the task is going to be.

Davies is a woman of enormous accomplishment. Born in Italy and migrating with her family to Edmonton at age 7, she remembers herself as a child who loved to learn. This bent would later lead to a BA and MA from the University of Alberta and a Ph.D. from King’s College University in London. Interesting jobs followed: researching for an encyclopedia of antiques and for a directory of national biography, the latter at London’s National Portrait Gallery, where she was surprised to find early glass negatives being stored in old tea chests, sometimes with tea leaves still in the bottom.

When she returned to Canada, she worked on Mel Hurtig’s Canadian Encyclopedia. Other highlights of her career have included writing or editing books on such subjects as Alberta in the First World War and a history of Italians in Alberta. She has worked with museums, curated exhibits and written and performed her own poetry. A lot to cover in a single volume, and this memoir does, in fact, feel a little abbreviated. At times it falls into summary, which deals efficiently with a surplus of material but keeps the reader at a distance and uninvolved.

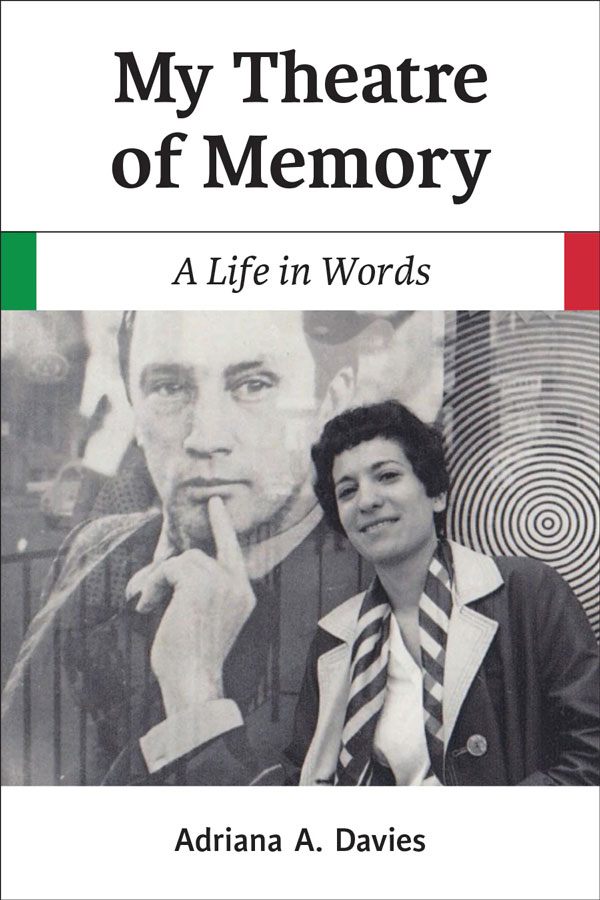

One of the more affecting sections of Davies’s book shows what she can do when she allows herself the necessary space. It deals with a visit to Edmonton by Montreal poet and troubadour Leonard Cohen when Davies was still at the U of A. Davies had met Cohen at one of his readings. At a second event, when Cohen both read and sang, she sensed that he was performing just for her. She told him so at a party later, and he confirmed that this was so. He also told her that she had beautiful eyes. When they parted ways, Cohen gave Davies a miniature rosary, a memento he said he had kept with him always.

I was not surprised, nearly a lifetime later, to find a photograph of that rosary in Davies’s memoir. Its presence there, it seemed to me, said something about one reason that people feel the urge to review their lives on paper. It is, I would submit, the impulse to declare, with the poet of old: “Time, you thief, who love to get/ Sweets into your list, put that in!”

Merna Summers is an Edmonton writer.

_______________________________________