Reinie Jobin, a stocky 68-year-old with porcupine- quill hair, drives along a rutted road beside the community of Little Buffalo. He stops at regular intervals to point out oil and gas wells, pipelines and work camps. What was once pristine forest, where Jobin’s people—the Lubicon Cree—hunted and trapped, is now a busy industrial zone. “They stole this country off us,” he says. “You be an Indian for a day and see it first-hand.”

More than a century after the federal government started signing treaties with Aboriginals in northern Alberta, the Lubicon still don’t have a land claim settlement. The last round of talks broke off in 2003. Meanwhile, the provincial government continues to grant oil and gas companies permission to extract resources from the 10,000 square kilometres of wetlands, muskeg, spruce, pine, poplar and birch that the Lubicon claim as their traditional territory. Now the Lubicon face the next wave of development: oil sands activity.

Jobin, a Lubicon elder, has become an unofficial tour guide for the reporters and human rights activists who regularly come to see his people’s plight first-hand. As we drive into Little Buffalo, it is clear that the oil and gas development happening right outside the community is not benefiting the Lubicon, even as it enriches corporations and governments. Little Buffalo is dirt poor and has almost no infrastructure—only a school, a tiny nursing station and a water station where community members fill large barrels to take home. With no running water in their homes, residents use outhouses and regularly drive an hour each way to and from Peace River to buy bottled water. Little Buffalo has no gas station, convenience store, grocery store, seniors centre or community hall, despite having a population of around 500. All the roads are gravel. Most houses are old and rundown, and many are extremely overcrowded.

Despite these conditions, Jobin says, community members fight to preserve their traditional way of life. It’s mid-September when I visit, and many Lubicon are out hunting moose, a staple of their traditional diet. A family cuts up moose meat outside their house. Elsewhere, the meat dries in smoke shacks. In one yard, a hunter has posed a moose head on top of her ATV.

The Lubicon plight began in 1899, when treaty commissioners, signing up Aboriginal people under Treaty 8, missed the Lubicon. Land claims negotiations didn’t begin until the 1980s, even though the Lubicon had asked for the creation of a reserve in 1939. Meanwhile, the provincial government granted numerous mineral leases within traditional Lubicon territory. The Lubicon tried to get a court injunction to stop the oil and gas development in 1982, but failed.

Unlike many other First nations in Canada, the Lubicon managed to continue living a traditional lifestyle, relying on hunting and trapping for their livelihood, until fairly recently. It was only in 1979 that the first road was built into their traditional territory to give companies access to the vast oil and gas reserves in the area. Soon afterward, most Lubicon members, no longer able to support themselves off the land, became welfare recipients.

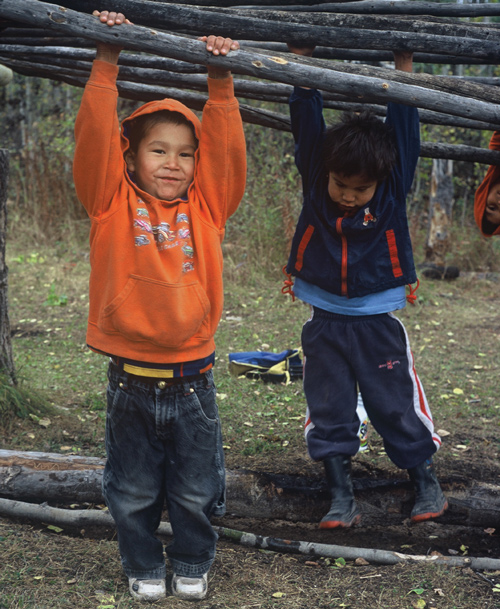

A rack for drying moose meat doubles as a makeshift playground. (Lori Willocks)

Over the many decades that this saga has been playing out, the federal and provincial governments have employed some questionable tactics. An Indian Affairs official arbitrarily cut 75 names from a Lubicon membership list in 1942, meaning those members would no longer have any Aboriginal rights. In the early 1980s the provincial government tried to turn Little Buffalo into a provincial hamlet, which would have made it ineligible for reserve status. In 1991, in order to reduce Lubicon membership, the federal government created the Woodland Cree Band and tried to entice Lubicon members to join with promises of money and homes with running water.

According to Jobin, alcohol and drugs became a problem in the community only after the first road was built. He adds that the Lubicon didn’t have to deal with pollution before then, and no one had to live on welfare. The industrial activity around Little Buffalo reminds him of white settlers killing off the buffalo. “It’s genocide,” he says. “All the Lubicon are trying to do is preserve their way of life.”

The Lubicon are particularly worried about oil sands activity because it has proven to be much more environmentally destructive than conventional oil and gas development. So far, it has been confined mostly to the Athabasca oil sands north of Fort McMurray. But the Peace River area is garnering an increased amount of interest from companies anxious to extract as much bitumen as they can, as fast as they can. Currently, the Lubicon are most concerned about an oil sands project being planned by Signet Energy and Deep Well Oil & Gas.

The 10,000-square-kilometre area the Lubicon claim as theirs is deemed provincial Crown land by the provincial and federal governments. However, both governments have agreed to set aside 247 square kilometres for an eventual reserve, pending an agreement. One chunk of that reserve land is at Haig Lake, one of the Lubicon’s traditional communities, right next to the proposed Signet project. Signet has already drilled three test wells in the area; the company states on its website that the project will require that 350 to 500 wells be drilled to recover the estimated 1.2 billion barrels of bitumen beneath the ground.

The Lubicon first became concerned when members saw representatives of Deep Well clearing land and building access roads in the Haig Lake area. At that time, the company didn’t have approval from the Alberta Energy & Utilities Board to do so. Since then, Surge Global Energy, the parent company of Signet Energy, has signed an agreement with the Lubicon promising it won’t proceed with oil sands development near Haig Lake without Lubicon approval. Leigh Cassidy, executive chairman and CEO of Signet, declined to be interviewed about the company’s plans.

Meanwhile, the Lubicon are trying to keep track of what other oil sands projects could be in the works. In June the provincial government sold oil sands leases on 50,000 hectares of Lubicon-claimed territory. Shell Canada and Penn West Energy Trust are already operating in the Peace River area and have announced they plan to expand their oil sands activity. Other companies have large leases nearby. Both Penn West and Shell are considering building oil sands upgraders in the Peace River area—a strong indication that activity in the area will be rapidly increasing.

This threatens further destruction of the boreal forest. Elder Joe Laboucan fondly recalls a time when he could trap lynx, fishers, muskrats, beaver, squirrels and martens. His trapline, 22 kilometres east of Little Buffalo, is now surrounded by industrial development. “It used to be nice and peaceful in those days. You didn’t hear nothing. Now it’s a big difference,” he says, adding that he’s caught “hardly anything” in the last two winters. He also remembers drinking water from lakes, rivers and creeks. Lubicon no longer drink water from their own land, out of fear it’s contaminated. “In the old days we’d go hunting and camping and get water any place,” he says. “We don’t do that anymore.”

It’s obvious when you meet Bernard Ominayak, the Lubicon chief since 1978, that he retains a strong distrust and anger toward both governments. On an overcast fall afternoon, he sits behind his desk in the tiny Lubicon Lake Indian Nation band office, surrounded by binders, rolled-up maps and boxes of files. His long, grey hair is pulled back into a ponytail and he’s clad in jeans and a striped blue shirt. He is soft-spoken. He appears tired but still defiant.

Displayed prominently on the wall is a plaque from his membership, which reads, “For Chief Ominayak, for never failing to provide leadership no matter how rough things get, and especially for always thinking of the children and grandchildren first.” Photos of elders line his office walls. “They’re all gone now,” he says sadly.

“We don’t know what’s coming,” he says when asked about potential oil sands development, “The biggest fear that we have in the tar sands projects is water. Are they going to be injecting steam? They seem to think that water is a cheap and accessible resource.”

Ominayak is also worried about the potential health impact of pollution associated with oil sands projects. Asthma and skin rashes have already become more commonplace. The community has been plagued by stillbirths. At the local cemetery—full of colourful little houses instead of tombstones—lie the graves of some of the stillborn children. The crowded living conditions also take a toll. Twenty-six members of the community are taking medication for tuberculosis. Ominayak says industrial development near the reserve has already had a “drastic” impact on the Lubicon. “Our people are forced into a situation that is not by choice. We want to try and live a life that our people are accustomed to as much as possible, but there are other interests that are overtaking things. And the governments are sitting back and not willing, not prepared, to do anything.”

He becomes visibly angry when asked why a settlement hasn’t been reached after more than two decades. “We’re not prepared to get on our hands and knees and beg to either government. They may feel they can just throw a bone to us and we’ll grab it. I think we’re beyond those days where they can come to the Indians and give them, they used to call it beads and trinkets…. We’re beyond that point. We’re human just as much as everybody else. We may be brown, but still. There’s still racism and people look down on our native peoples a lot, but we’ve got every right to be treated equally and fairly.”

Ominayak believes the government attitude is that the Lubicon “are in the way of development. There’s no interest whatsoever by the Alberta government or industry to start sharing the resource to meet the needs of the native people that they’re stealing off. They’re outright stealing is what’s happening.”

As I interview community members, it becomes apparent that most still support their chief even though the claims process has dragged on for decades. Laboucan says he is behind the chief “through thick and thin. I think he’s doing a good job. He’s trying to get the best for his people. He won’t give in.”

But some residents question why negotiations are dragging on so long. Veronica Whitehead has lived in Little Buffalo most of her life, but she’s a member of the Whitefish Lake First Nation and isn’t eligible to vote in Lubicon elections. She believes the Lubicon should take what the governments are offering. Her grandmother, who was a Lubicon member, recently died of tuberculosis. Whitehead says her grandmother’s house leaked and had mould in it. “I think we’re the only people left in Alberta or Canada that don’t have indoor plumbing,” she says. “Does it make any sense?”

A major bone of contention is whether Treaty 8 covers the Lubicon. The governments say it does, but the Lubicon argue that no representative of their band ever signed the treaty, and therefore they have Aboriginal title to the 10,000 square kilometres.

Alan Maitland, the provincial negotiator for the Lubicon file, says the treaty commissioners recognized in 1899 that they hadn’t signed up all the Aboriginals who would fall under Treaty 8. They estimated they’d missed 500. But, he says, as a matter of law the Aboriginal title of every First Nation person living in the area was extinguished when the treaty came into effect. He says the province has successfully negotiated land claims settlements with other First Nations that were excluded from Treaty 8 but have agreed to be bound by it. “We’re just not having any luck with the Lubicon,” he says.

According to Maitland, the Lubicon are entitled only to the 247 square kilometres of reserve land that the three parties have agreed to, and they don’t have ownership rights over their traditional territory. “We disagree fundamentally that it’s their land,” he says. “The resources belong to Alberta.”

Elder Reinie Jobin in front of his Little Buffalo home. (Lori Willocks)

He says the Lubicon do have the right to hunt, fish and trap in their traditional territory, and that the government has committed to consulting with First Nations about oil sands activity on that land. So far, he says, the Lubicon have refused to consult.

“If they were like other First Nations in the area—who have had reserves created for them, had infrastructure provided, had compensation money provided for them and are now thriving, are now doing very well and managing their own affairs and having oil companies coming into their reserve and doing business with them—my guess is the Lubicon would be quite far ahead and they would be doing very well.” Bands such as the Woodland Cree and Loon Lake First Nations benefited from new community infrastructure, including schools, administration offices and health centres. But the Lubicon, Maitland says, currently “languish” because they weren’t willing to sign.

“I can assure you that certainly my knowledge is we’ve done everything we can from a provincial point of view to try and bring some settlement to bear,” he says. “This is not blank-cheque city. It’s not ‘We want a settlement and here’s the chequebook.’ We can try and make a good settlement for a First Nation, but it’s got to have some relevance to everything else we’ve done in the province. We have tried to do that, and we have had great success with everybody except the Lubicon.”

Glen Luff, a spokesperson for Indian & Northern Affairs Canada, has a similar position. “We feel that we’ve made a very reasonable offer that’s in line with other land claims,” he says. “We would say that our compensation is fair.” He says the federal government has offered to enter into talks with the Lubicon on a self-government framework agreement, which would then lead to a final self-government agreement. However, the Lubicon “are demanding that Canada recognize they have existing rights to self-government as part of a land claims settlement agreement.” The federal government says that specific Aboriginal rights for individual First Nations have to be proven in court. Otherwise, self-government rights must be negotiated between the two levels of government and the Aboriginal group. Luff says the federal government has offered to go back to the table but the Lubicon have refused.

Kevin Thomas is a land claims negotiator for the Lubicon. Though not Aboriginal himself, he got involved with the Lubicon claim while he was still in high school, circulating a petition and writing letters because he was “shocked that this kind of injustice was allowed to exist in our country.” The Lubicon hired him to represent them in 1998. According to Thomas, approximately $13- to $14-billion in resource revenue has come out of traditional Lubicon territory over the years. Meanwhile, in the last round of negotiations, he says, the federal government offered $20-million in compensation and the province offered $2-million. “That’s not to say that the Lubicon are going to hold out for $13- or $14-billion,” says Thomas, “but they at least need to have something that gives them a decent income with which to be self-sufficient.”

As for self-government, Thomas says the Lubicon are being forbidden to negotiate for it until they surrender their inherent rights. “If you sign off on all your rights before you’ve been able to negotiate self-government, all that you’re going to get back from the government is what they’re willing to give you,” Thomas says. “That’s not a good way to go into negotiations.”

Lubicon supporters often point to the continued lack of running water and sewage systems as the strongest evidence of neglectful treatment by government.

In March 2006, Indian & Northern Affairs Minister Jim Prentice promised he would work to ensure safe water conditions on first nations reserves. In a March 27, 2006, letter to Prentice, Ominiyak pointed out that the Lubicon have to drive 100 kilometres to buy bottled drinking water and some elders need to be helped to their outhouses, especially in winter. He also claimed all traditional sources of drinking water had been contaminated by “resource exploitation activity.”

According to Thomas, the Lubicon submitted a proposal in July 2005 for the federal government to provide running water and sewage systems for 10 Lubicon elders. As of November 2006, the federal government had offered $250,000 to provide water and sewers in the 10 houses, but the funding would cover only the installation of sinks, toilets and water and sewage tanks. It would not include funding for delivery of water or disposal of sewage. The Lubicon want their own water treatment plant and sewage lagoon built in the community, but the federal government has offered no funding for that.

However, a federal official involved in land claims negotiations has a different perspective. He claims that, during the last round of negotiations, the federal government offered to provide a water truck and to have homes retrofitted with water tanks in advance of a final settlement, but that the Lubicon rejected the offer.

“They’ve decided strategically that they have a far more effective case in the public eye—with reporters like you and lots of other Canadians and particularly people overseas—on the basis that they live in Third World conditions with no running water or sewer. frankly that is by choice,” says the official, who has requested anonymity. “The part that’s dishonest is to go out and say that the Government of Canada wants it this way, that they’re in Third World conditions and the federal and provincial government won’t do anything about it.”

Chief Ominayak could not be reached for comment, but Thomas expresses outrage at the allegation, saying he is “shocked by the pettiness and the dirty tactics of the federal side… That kind of thing almost doesn’t deserve a response because it’s so horrifically wrong and it’s just astounding that they’d sink to that level. The real facts are no, they haven’t made any such offer of putting in water with no strings attached.”

Thomas says such an allegation is indicative of why there’s no settlement in place. “I find it frustrating to hear this kind of attack. These people have met the chief, sat across the table from him, and to sling that kind of mud at him when they know better tells you why there’s no settlement yet of the Lubicon.”

Because there’s no documentation of what exactly was said during land claims negotiations, the truth is impossible to verify.

Meanwhile, the federal governement continues to receive a black eye internationally for the unresolved land claim. In May, a united nations committee urged the federal government to resume negotiations and “conduct effective consultation with the band prior to licences being granted for use of land the Lubicon claim to own.” The united nations first criticized the Canadian government over the Lubicon situation in 1990, when the Human Rights Committee concluded that Lubicon rights were being violated by “historical inequities” as well as “more recent developments.” Amnesty International has also frequently criticized the federal government for failing to resolve the claim. In 1984, the World Council of Churches wrote a letter to then prime Minister Pierre Trudeau stating that industrial development on Lubicon land “could have genocidal consequences.”

Craig Benjamin, an indigenous-rights campaigner for Amnesty International Canada, says part of the problem is the way Canada handles land claims. “I think there is a deep structural problem in the way disputes like this get resolved. Governments take on the role of fighting against the indigenous people, of trying to undermine their claim, dispute their claim, trying to minimize the extent of settlement… they really don’t know how to respond or how to deal with a community that says, ‘We won’t accept a diminishment of our rights.’”

Despite the fact that the Lubicon have received widespread national and international support, it’s a different story in Alberta, where people aren’t at all concerned, says provincial negotiator Maitland. “I think if you check with politicians that get letters, they may get two or three from Hamilton or places like that, but it is not a major issue in Alberta—or, I would even go so far as to say, in Canadian society.”

This angers Reinie Jobin. “democracy is being very abused,” he says. “When somebody’s human rights are being violated, so are yours. The Canadian public should realize that and start doing something about it.” As for the Lubicon, they’ll continue their struggle. “We’re not going to quit,” Jobin insists. “It’s a fight for the survival of our people.”

Amy Steele is a staff writer for Calgary’s Fast Forward Weekly and a previous contributor to Alberta Views.