Poleconomy, a 1980s family board game billed as “The Game of Canada,” has you move plastic beaver tokens, buy real-life companies and try to amass the most money. Occasionally you get elected prime minister and can set interest rates and corporate taxes—raising them through the roof, obviously, if your opponents are vulnerable. You can be easily ruined; the competition is cutthroat; the power of being PM is exhilarating. I loved the game. So too, apparently, did a young Brad Wall. By comparison Monopoly is as insipid as Candyland.

One of the spaces your beaver token can land on in Poleconomy—one of the entities for sale—is the Fraser Institute. The four-decade-old think tank is officially non-ideological; its mantra “If it matters, measure it” might as well be a dressmaker’s. But fans and critics alike know the Fraser Institute to be our country’s fiercest champion of the free market and small government. Such an advocacy group is a perfect match for a game in which government’s main role is to punish the rich. In actual fact, the Institute bankrolled Poleconomy, with founder Michael Walker selling board-square naming rights to Canadian companies in the early 1980s, raising a million dollars, and producing thousands of copies of the game.

Poleconomy is vintage Fraser Institute. The well-funded think tank ($10.7-million in revenue in 2015) relentlessly pushes its message—whether overtly, through its dozens of annual research reports, or covertly, as in a libertarian recruitment tool marketed to families as “The Game of Canada.” The Institute’s fellows and alumni (Tom Flanagan, Danielle Smith, Ezra Levant etc.) are frequent pundits. The think tank has placed columnists across the Postmedia newspaper chain; currently three at my hometown Calgary Herald alone. But what Fraser really craves is mainstream news coverage. In 2015 the think tank told donors it received 28,338 mentions in news stories—or nearly 80 every day—and estimated the equivalent ad value at $16-million. Its self-promoting gimmicks (Tax Freedom Day; annual school rankings) are often reported as news.

Whatever news coverage the Fraser enjoys owes largely to how it engages with media. Case in point: Last winter an email landed in media inboxes across the country with an invitation to “Economics for Journalists.” For years the Institute has hosted these annual three-day seminars in Toronto and Vancouver. Hundreds of Canadian journalists have attended the “graduate seminar-style program.” For years I’ve deleted the email in the same way I would ignore an offer to study comparative political theory with Tom Mulcair.

But I lingered on the invite this year. Was the Fraser Institute in fact trying to propagandize rooms full of (one would hope) professional skeptics? What media did attend, and how did they respond? Surely a research institute staffed by self-respecting adults—even a “research institute” driven by ideology rather than the pursuit of truth—couldn’t in good faith promise “a forum of learning, questioning and critical analysis” and then subject attendees to little more than a marathon game of Poleconomy.

The Institute has evidently dropped the “vinegar” of shame for the “honey” of re-education.

Skepticism serves journalists well, but its distant cousin, Cynicism, shuts down chances to more deeply understand issues. Here was an invitation to learn—a little about economics perhaps, but definitely something about the Fraser Institute’s relationship with media.

I applied. To my surprise I was accepted.

The opening night of “Economics for Journalists,” May 2016 edition, was a suit-and-tie affair in a private room at a French restaurant in downtown Toronto. Some 25 journalists from across the country made small talk and awkward jokes about the “economics of journalism” (i.e., dire). We were youngish and mostly from TV, radio and smaller newspapers.

Over a dessert of chocolate mounds we were introduced to our hosts: Fraser Institute executive VP Jason Clemens, two staff members, and the weekend’s presenters—two economics professors from Wisconsin and one from McGill University.

We’re so happy you’re here! Mark Schug, one of the Wisconsinites, told us by way of introduction. We have so much respect for journalists. You gave up so much of your time.

It’s no big secret that many on the far right, from Donald Trump to campus conservatives, view the media with a special contempt that the far left saves for fracking lobbyists and mud-boggers. Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek—father of neoliberalism, and inspiration for both Stephen Harper’s MA thesis and the Fraser Institute’s creation in 1974—wrote in his essay “The Intellectuals and Socialism” that media are part of a dangerous professional class of “secondhand dealers in ideas,” who “need not possess special knowledge of anything in particular, nor need… even be particularly intelligent.” Former Fraser fellows Lydia Miljan and Barry Cooper, in Hidden Agendas: How Journalists Influence the News, updated Hayek’s thesis, dubbing journalists “narcissistic personalities” with naked left-wing leanings. The Institute also used to publish a National Media Archive, a regular report on Canadian media bias.

But it has evidently dropped the “vinegar” of shame for the “honey” of re-education.

It was time for Clemens. He anticipated some friction, he said. But in truth, the Institute is non-partisan and non-ideological, wanting only “to improve the lives of Canadians.” Yes, he said, some call the Fraser Institute “the intellectual wing” of the Conservatives. “But that’s not true!” Clemens professed admiration for the Saskatchewan NDP’s Roy Romanow; prime minister Harper, he said, was a colossal dud.

We were 20 minutes in and no one had said the words “free market” or “small government.” Did the Institute view us journalists as Hayek had—thick as bricks, self-important, incapable of even cursory research on our dinner hosts? Clemens clearly didn’t think we could differentiate Romanow’s austerity from Harper’s spending public money like a pirate on shore leave. All we were supposed to hear was praise for socialists, the Fraser Institute’s ideological free-agency thus proven.

Now the best part, Clemens said, rubbing his hands. Time for questions—any questions. Someone asked who funds the Institute. Some 3,000 individuals, the VP said. “What do they expect in return?” another journalist called. Our donors, Clemens replied, love Canada.

I wondered if he’d mistakenly brought his script for junior high school visits. Senior Globe and Mail reporter John Ibbitson once wrote of think tanks that “those on the right twist and distort data to prove the country is overtaxed and underproducing. Those on the left use the same data to prove that society is increasingly unequal and unjust.” This is a fair criticism of institutes on the ideological margins, to which the first rule of journalism especially applies: “Follow the money.”

One woman asked: Do you think journalists are stupid?” Clemens was aghast.

Clemens didn’t tell us that the Fraser Institute’s foundation funding far exceeds donations from individuals, and that the climate-change-denying US billionaire Koch brothers and libertarian Donner Foundation are among the Institute’s big supporters. Too much proactive transparency, however, might not be in the Institute’s interest, since their charitable status (also unmentioned) means they’re tax exempt and that the Canada Revenue Agency theoretically limits the Institute’s political activity.

But Fraser donors, we were assured, get nothing in return. “We don’t do ‘pay to play,’” Clemens said. A Fraser benefactor, he explained, once demanded to see the results of some research in advance. The Institute refused, and the donor later seethed at the published results.

I raised my hand. “It’s hard to take you seriously,” I told Clemens. “How is it that all of your research points to a free-market solution? If you commissioned independent research, and its conclusion supported more regulation, would you suppress those findings?”

Clemens laughed and explained that different research outcomes come from asking different questions. What he didn’t say was that of course his think tank’s research has predetermined conclusions. Free-market-loving donors don’t fund happy findings about public healthcare any more than the Broadbent Institute would publish “12 Surprising Downsides to Raising Minimum Wage.”

Our hosts, it seemed, were harmless data junkies funded by mathaholics who hoped better numeracy would create a more loveable Canada. The night ended with a question from a woman at a table to my right: “Do you think journalists are stupid?” Clemens was aghast.

Later, at the pub, another reporter called the evening “a timeshare presentation.”

Day Two began in a hotel conference room with omelettes and strong coffee. We journalists formed three sides of a square, with a projector screen in the gap between the tables. Eight hours of economic theory lay ahead; the mood was upbeat. Professors Schug, Scott Niederjohn (the other Wisconsinite) and Bill Watson (McGill) took turns presenting, while two Institute staff observed from the back of the room.

Schug opened with a disclaimer. “We’re not journalists,” he said. “We’re not telling you how to do your job.” The Institute merely hoped that media would “choose a [story] angle based on what you learn here.” Harmless, really—but for the fact that reporters now write several stories every day and edit others, write headlines, moderate social media, do radio and TV spots etc. They increasingly rely on angles and sources they know or can dig up quickly. TV and radio in particular need sound bites. The Fraser Institute, by offering predictable and prepackaged “content,” preys on modern media weaknesses. (Canadian cultural critic George Fetherling blames the media as much as think tanks for the dumbing-down of news, calling much modern journalism “the outsourcing of news” to “well-dressed disinformation factories.”)

The retired professor circled the room, pausing and making eye contact. “I want to understand why you’re here,” he said. “Why give up your weekend?” He answered his own question by explaining opportunity costs: everything has a price, which includes forgone opportunities. We journalists, he said, were getting a free trip to Toronto in exchange for “education and gratitude.” Schug’s including “education” as a cost to us rather than a benefit seemed telling, if inadvertent. He then led the room in an incantation: There’s no such thing as a free lunch. There’s no such thing as a free lunch…

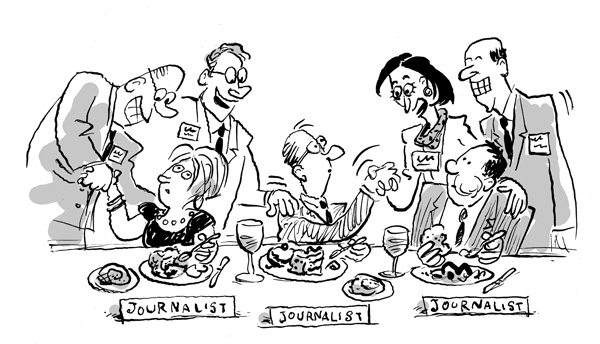

Illustrations by Gerry Rasmussen

The professors took turns presenting on supply and demand, “the tragedy of the commons,” comparative advantage and the gains from voluntary exchange. Much of the material was basic enough. It’s never bad to remind people to think about incentives, primary and secondary effects of choices, unintended consequences. But just as things threatened to get educational, our hosts would reassure us of their agenda.

From concepts we pivoted to assumptions. The language became leading. Rather, for example, than we citizens needing services often too expensive to pay for out of pocket (e.g., chemotherapy, a K–12 education) we have “an entitlement problem” that only more privatization can solve. Our worry should not be how to maintain public safety and orderly markets but how to “escape” regulation. Taxes, meanwhile, are a “burden” requiring “relief”—think haemorrhoids rather than roads, hospitals or police.

We wondered: Were the professors propagandists, true believers or simply guns for hire?

Or take professor Watson’s language around supply management. Canadian farmers are “culprits” of subsidized agriculture. We need fear the “evils” of protectionism and tariffs. Opponents of free markets are “incoherent”—when they’re not “militant,” “aggressive” and “creative.”

The downsides of deficits merited several overhead slides; presumably there are no upsides. And scant evidence was given for how the cost of public services is ruining Canada. We were similarly spoon-fed on taxes (“Too high; let’s move on”). Here, I thought, was a missed opportunity to differentiate, for us slack-jawed “second-hand dealers,” the relative pros and cons of sales taxes, income taxes and property taxes.

Other than public financing for sports stadiums (no economic justification!) and minimum-wage increases (beware unintended effects!), the professors offered little insight into many issues journalists are covering today—what role regulation or the lack thereof plays in Vancouver’s and Toronto’s overheated housing markets, for example. Or why tens of millions of people in the UK and US—especially conservatives—have lately voted against free trade. Or our leaders’ failure to explain to the torch-waving mobs that a tax on a negative externality (e.g., CO2 emissions) is designed to change harmful behaviour rather than enrich governments.

As for the examples given, they often skewed to the ridiculous. Venezuela’s scarcity of goods is a lesson in why we “shouldn’t screw with markets.” Meanwhile price controls, such as affordable housing, do more harm than good. For evidence, we watched a 30-year-old video on how New York City’s unique rent control system was abused in the 1980s by celebrities Mia Farrow and Carly Simon. Case closed.

The sessions ran at a Gatling-gun pace. Rarely did the professors ask if we understood the concepts or if examples were relevant. The odd mid-session question was invariably dismissed with “We’re getting to that” or “We have to move on.” One reporter asked whether agricultural subsidies protect jobs. Another wondered what price you can put on preserving unique culture (e.g., Quebec cheese; Canadian fiction). I asked whether economists could factor in the cost of food insecurity. Day Two flew by in a haze of non-answers.

Full transparency: The second and third days of “Economics for Journalists” opened with requests for feedback, with the profs seeking our “Aha! moments” from the day before. One reporter said the discussion of minimum wage went by very quickly “and I’m not sure if that was deliberate or not.” Another said we hadn’t talked about Aboriginal economic issues. One said he hadn’t realized how much isn’t calculated in GDP: unpaid child care, for example.

The point about stay-at-home parents had actually come up during a session otherwise meant to show us how a rising GDP means economic progress. As a non-specialist, even I knew this claim to be highly dubious. No less a magazine than The Economist—whose authority the professors cited constantly—wrote in a 2016 cover story that GDP “has become shorthand for material well-being, even though it is a deeply flawed gauge of prosperity and getting worse all the time.” Many things people value, from social media to uncorrupt courts, aren’t captured by the yardstick. Many things people resent—floods, oil tanker spills, 20-car freeway pileups—actually boost GDP.

That very Economist story was on newsstands April 30–May 6, the week of “Economics for Journalists.”

I did manage to chat privately with a Fraser representative about alternative measures to GDP, outlined in such books as University of Alberta professor Mark Anielski’s The Economics of Happiness. The person, whom I won’t identify, said they were aware of such ideas, and allowed that it would be interesting to discuss the differences.

I asked this person about Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons,” the famous essay published in 1968 that libertarians seize upon to assert that the commons—parks, forests, rivers, city streets, everything we own collectively—will be destroyed unless privatized. Along with everything Hayek wrote, this essay is Fraser Institute gospel. But Hardin concluded something very different, arguing that society must collectively regulate the commons. Realizing he’d been misunderstood, he wrote in another essay 30 years later that “[my] weightiest mistake… was the omission of the modifying adjective ‘unmanaged.’” He should have titled his original essay “The Tragedy of the Unmanaged Commons.” But Hardin’s substantial clarification didn’t make it onto the weekend syllabus.

The Fraser representative conceded some points and revealed that the Institute’s media classes had in the past struggled to attract participants, “because they’re seen as too libertarian.”

Perhaps to broaden the weekend’s appeal, “Economics for Journalists” now features games—an easy enough addition, since the Fraser Institute also teaches “basic economics” to thousands of junior- and senior-high students in Canada every year. One game involved buying and selling pretend goods to establish the market rate. Another entailed four reporters fighting to grab a limited number of goldfish crackers from “the high seas” (to demonstrate the sheer lunacy of unprivatized spaces—or unregulated public ones, perhaps).

Illustrations by Gerry Rasmussen

Later we were all given real gift cards; a reporter from the Maritimes got stuck with lingerie. He was later allowed an exchange. I could keep my Chapters card. Being forced to give it up, however, would have better reinforced the Fraser Institute’s dire warnings about central planning. Meanwhile, the lesson—clearly still relevant in post-Brexit UK and newly Trumped USA—was that free trade always makes everyone happier.

Some of the sessions’ content was useful—even fascinating. The professors would each briefly shed their ideological armour, visibly relaxing as they unpacked complex concepts rather than trying to shape our conclusions. Watson and Niederjohn broke down the unemployment rate and how to adjust dollar figures for inflation. The former practically buzzed as he explained the overnight interest rate. The latter, grinning and pausing for emphasis, gave what could almost become a TED talk on the bizarre nature of money (banks “create” money by lending to lenders, who lend to other lenders etc.). Schug allowed that the US housing market crash owed “partly” to financial industry greed—which seemed like conceding cigarettes cause cancer. (A 1999 Fraser Institute study actually challenged the connection between second-hand smoke and cancer, denouncing “junk science” as a threat to society because “instead of acknowledging the selectivity of its processes and the official desire for demonstrating predetermined conclusions, it invests both its processes and its conclusions with a mantle of indubitability.”)

Clemens reappeared to offer a useful primer on how to interpret government budget documents, defining terms and demystifying acronyms. “Let me put it to you this way,” he told us. “Alberta’s financial documents are a nightmare.” He said all governments do “shenanigans” and thus media “must be skeptical,” adding that public institutions, “for transparency purposes, should make it explicit” what’s going on. I should’ve asked if he felt the same about private institutions with charitable status.

My takeaway memory from the weekend is the “lesson” on externalities. At lunch one day, a reporter from Ontario and I discussed how the word “environment” hadn’t been mentioned even once. I asked the professors about that and was told: Wait. It’s coming.

Externalities are side effects or consequences not reflected in the prices of goods or services. A positive externality is the pollination of your neighbours’ crops by your honeybees. Negative externalities include air and water pollution—and antibiotic resistance, CO2 emissions, depleted aquifers, rare cancer clusters, mercury in tuna etc. Externalities are frequent fodder for journalists, a puzzle for economists and policymakers and an existential threat to humans.

Yet when the time finally came we were shown an excerpted video of three people. A man named Art sells a bag of potato chips to Betty and then leaves. (Betty is the same actor in drag.) She proceeds to eat the chips noisily and messily, to the annoyance of the third person, Carl. “He’s harmed,” the narrator explains. “He didn’t get anything, but he has to listen to all that crunch-crunching and yum-yumming. Pretty noisy!” We were meant to guffaw.

That was the extent of our lesson on externalities.

For all its media reach, big budget, prolific alumni and vast reams of reports, the Fraser Institute up close turns out to be pretty sad. It barely conceals its contempt for a media whose legitimization it desperately seeks. It denies an agenda its donors are counting on. It offers no defence of “research” whose findings seem predetermined. And it’s ultimately not even that subtle in its propaganda—the think tank equivalent of a Jack Chick comic tract.

No doubt some attendees of “Economics for Journalists” went away impressed. Some were already on board with the Institute’s message. But reporters that uncritical, or that keen to steer their readers’ conclusions, hopefully aren’t long for the profession anyway. Others seemed as disingenuous as the Institute itself. One fellow contributed nothing to the seminar discussions but fairly gushed about his visit to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

One question that came up at the pub after the sessions was whether the professors were in fact propagandists, true believers (It’s not deception if it’s the truth!) or simply guns for hire. Hard to say. Frankly, much about the Institute seemed artificial. That board game, Poleconomy, that the think tank published to help Canadian kids understand the joys of free markets and callousness of government? It was a copy of a version published by a libertarian New Zealander. An Australian edition exists too, and apparently patents were issued for the US, UK and South Africa. For all I know, elsewhere the game is billed as “The Game of Russia” or “The Game of Congo.”

In Poleconomy you pay taxes to the government and get nothing in return. This has been the real experience of exactly zero Canadians. I remember Niederjohn, early in the sessions, describing our country’s healthcare system as “you spending someone else’s money on someone else.” I doubt the professor has lived in Canada; he doesn’t understand our culture. The latter applies to the Fraser Institute too.

But I did learn a few things in Toronto about economics. And I learned much about the Fraser Institute. While waiting for each day’s sessions to begin I would drink too much coffee and peruse the many free publications provided by the think tank. Among others, I came home with a copy of the Institute’s own The Essential Hayek. I’ve since skimmed the slim volume, which promises “basic insights” in “plain language.” It is no textbook. No mention, either, of the economist’s plain disdain for journalists.

The book does, however, and without irony, quote John Maynard Keynes: “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist.”

Evan Osenton is editor-in-chief of Alberta Views. His previous AV story, “The Gap” (Nov 2015) explored medicare’s lack of dental coverage.