Little did Ralph Klein expect to ignite a firestorm when he joked at a 2004 election rally that two women had been “yipping” at him about AISH (Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped) payments. “They didn’t look severely handicapped to me,” he said. “I’ll tell you that for sure. Both had cigarettes dangling from their mouths, and cowboy hats.” And he vowed that, if re-elected, “We will look at potential and absolute abuse of the system and cut those people off.”

Uh-oh. Bad move, Mr. Premier. “The thing about Albertans is that we do care about people in need,” says Professor Lois Harder, a political scientist at the University of Alberta. She points out that scaremongering about fraudulent benefits claims may have worked when Klein first ran for premier—when Alberta faced a deficit. But if people were still slipping through the system after he’d been in power 12 years, the public was liable to think he was at fault.

Thus began the MLA Review Committee on AISH, chaired by Strathcona MLA Rob Lougheed, chair of the Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities, which reported back in February 2005 with 11 recommendations. Two months later, Seniors & Community Supports Minister Yvonne Fritz announced forthcoming action on six of these. One key recommendation was an immediate $200 increase in monthly AISH benefits (then $850 a month), to be followed by reviews and increases every two years—not, as critics quickly noted, indexed annual increases. In 2008, after the biennial review, the maximum benefit now stands at $1,088—give or take a few deductions and exemptions.

Why does a province that runs multi-billion dollar surpluses squeeze its most vulnerable citizens for every last dollar?

Those deductions and exemptions triggered a second crisis, in October 2005. AISH recipients Donald Fitfield and Curtis Roth filed a class action asserting in their statement of claim that “…the Government’s Underpayment Policy and its debt collection practices were illegal, inequitable, harsh and oppressive.”

In February 2006, the Court of Queen’s Bench oversaw an out-of-court settlement that included clients of programs under the Widows’ Pension Act, the Senior Citizens Benefits Act (1980) and the Social Development Act (1970) as well as AISH. Early estimates suggested that Alberta’s 62,000 single parents, persons with disabilities and unemployable early widows stood to potentially benefit by up to $100-million from the settlement.

In actual fact, only 6,714 recipients claimed the compensation, partly because many people in those programs believed or discovered they were not eligible, and partly because the paperwork was confusing. Still, Ralph Klein’s comments and the lawsuit raised significant questions about AISH.

Namely: Why is a province that regularly runs multi-billion dollar surpluses squeezing its most vulnerable citizens for every last dollar? The haphazard development of the province’s social services policies for persons with disabilities seems to have created as many barriers as it levels. Apparent benevolence on one hand clashes with murkier motives on the other: distrust and paternalism.

Paternalism? Alberta at one time in our history sterilized people with mental and physical disabilities. From 1928 to 1972, the Alberta Eugenics Board ordered 4,725 sterilizations of “defectives.” Some 2,822 surgeries were performed. In 1972, citing human rights, Peter Lougheed’s government repealed the eugenics legislation.

Leilani Muir, a former resident of the Provincial Training School for the Mentally Defective (PTS) in Red Deer, brought this injustice into the spotlight in 1996. Madame Justice Joanne B. Veit found the province liable for surgically destroying Muir’s Fallopian tubes in 1959, when she was 14, without her knowledge or consent. Three other girls had the same surgery the same day. In 1996, the court awarded Muir $750,000 compensation, plus legal costs. “No amount of money,” said Muir, “could ever make up for the hurt I went through and that will be there until the day I die.” Subsequently, more than 700 other former PTS residents have sued and won settlements.

National Film Board interviews with other former residents reveal the level of coercion and deceit involved. Rita Haggerty, a dignified and articulate polio survivor, recalled that, “I was taken in front of the Eugenics Board and told that if I wanted to get out, I would have to have sterilization. I plainly told them to leave me the way my body was. They said, ‘Then you don’t get out.’ ” She lived in the PTS for nearly 50 years.

Already, then, some people with disabilities were clamouring to be released. Their powerful urge to be autonomous led to a new policy of de-institutionalization and community living—supported in part by AISH, which began in 1979.

“Some people with disabilities were sick and tired of being told when to get up, what to wear, what to eat, when they could come out,” says Bev Matthiessen, executive director of the Alberta Committee of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD). “People in the disability community really want to work. They have a right to be full citizens of Canada, which means that barriers must be removed, and to have all things available to them such as education, transportation and housing.”

Until recently, though, the Alberta government did not seem to have any central plan or goals in place for its disability policies. In 2002, the Premier’s Council on Disability released the “Alberta Disability Strategy,” which concluded that, with 11 ministries handling 34 programs, “Albertans with disabilities continue to experience large inequities and fragmentation in service and support.”

In 2004, according to Rob Lougheed, most of the disability services and programs were amalgamated into the Seniors & Community Supports ministry. Integrating the services, though, is an ongoing process, complicated by the incredible diversity of the client base and their needs. There are so many different kinds of disabilities. As Michelle Kristinson of the MS (Multiple Sclerosis) Society says, “Someone with a developmental disability has nothing in common with someone from the oil patch who now has MS. Yet we’re expected to speak with a common voice.”

After years of amendments and piecemeal adjustments, new and completely overhauled AISH legislation came into effect on May 1, 2007.

In less than 30 years, the AISH program has grown explosively, from 1,000 recipients to 36,000. But there are still only 144 AISH caseworkers for the whole province, carrying an average caseload of 250 clients apiece while juggling constant changes to regulations and to their duties. And they often change jobs. When asked whether they ever meet their caseworkers, a group of AISH recipients at a Calgary gathering respond with shouts of laughter and a resounding, “Yeah, right!”

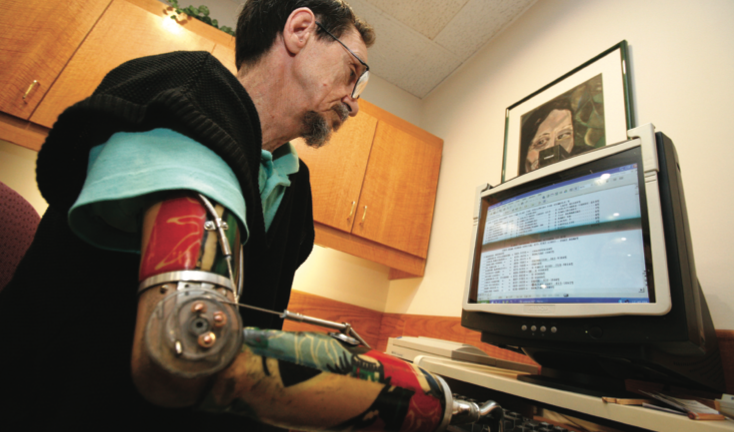

No wonder, then, that clients report a sometimes bumpy ride. Take Brian Laird, 58, who says he has been on AISH “since the get-go”—since the program started. In 1976, he suffered a horrendous electrical accident that literally cost him both arms and a leg. Although he could no longer practise his trade as a commercial cook, he was looking for paid work even before he got out of the nursing home where he was sent for rehabilitation. In 1988, he started working for the ACCD in Edmonton, where he has remained, in various capacities, ever since.

Laird says his most recent caseworker had just contacted him about what AISH considered to be an “overpayment.” “My worker changed and they did not realize I was paid twice a month,” he says. “She didn’t deduct enough. They did it all on the phone with me and sent an agreement in the mail. The plan was done quite fairly,” he hastens to add. But the result is that his monthly cheque will be docked (up to $100) until the overpayment is repaid. “I felt there was a lack of communication from one worker to another worker when she took over the caseload.”

When Laird first returned to employment, he kept very little of his paycheque. Until 2005, AISH only permitted recipients to earn up to $200 a month, and clawed back 75 cents of every dollar earned above that amount. Thus, a person who worked full time for a month at minimum wage might earn nearly $900, but net only about $360 in additional income—hardly anything, after you deduct the costs of transit, work clothes and lunch.

Since the MLA review, AISH doubled the exemption to $400 and decreased the clawback to 50 cents on the dollar. A key concern for Laird and most other AISH recipients is to keep their earnings low enough to maintain eligibility for AISH medical benefits. Medications, let alone special appliances or trained helpers, can cost hundreds of dollars per month.

Although AISH provides essential support, it also carries a stigma. Kathleen Biersdorff, who is self-employed, says her bank treats her as a high-risk client because she receives AISH: “When my car was totalled, the insurance company gave me a cheque to buy a new car. But my bank wouldn’t cash the cheque. They wanted to hold funds for a week, because I’m on AISH. I had already ordered the replacement car and now I couldn’t pay for it. I went to the bank that issued the insurance cheque and asked for a certified cheque. They wouldn’t give me one because an insurance cheque is good anywhere. I stood in the bank and cried. Finally the bank manager gave me a bank draft and her card, and told me to have my bank call her to confirm the draft. They did call her. I know, because I listened. And then they gave me the money.”

Biersdorff was one of about 15 people who attended a midsummer Disability Action Hall dinner at Calgary Scope Society, an outreach organization for children and adults with special needs. Most of those around the table looked “severely normal” enough to make Ralph Klein eat his words about what AISH recipients should look like. But they collectively attested that AISH monthly payments barely provide subsistence living.

Matthew Duckett receives AISH, and supplements his income by working at a McDonalds restaurant in Calgary. (Suzy Thompson)

Tom Brisbin is taller than average—six-foot-five, in fact. “My mother was quite surprised to find someone who is developmentally disabled could grow so big,” he says. But he can’t afford to buy clothes his size. “With my AISH, I’m only able to pay for my rent, my phone and my cable and nothing else. I need ‘big and tall’ clothes, and I can’t always afford them.”

Christina Stebanuk explains that, as a single mother surviving on AISH, she faces constant embarrassment because she always has to ask the school to waive her 10-year-old son’s fees for field trips, sports teams and even milk at lunch. And other mothers think she is letting down the school because she can’t afford to give him money for monthly fundraisers like pizza days. Sometimes she can’t even afford to bring a covered dish to a potluck dinner.

Calgary Scope staffer Patricia Okahashi says some clients have told her that when they tried to rent rooms or apartments, everything went fine until they revealed they were receiving AISH. Then the lessor wouldn’t rent to them.

Okahashi’s job title at Calgary Scope is “red tape person.” This seems to be an essential function for organizations that help persons with disabilities. Her counterpart at the Independent Living Resource Centre of Calgary is Mike Hambly, personal empowerment co-ordinator. Hambly’s job is to guide applicants through the maze of programs and regulations surrounding the benefits they need.

“What I do is help people in their daily battle for existence,” he says. He offers his own case as an example. A car wreck in 1996 left him blind and paraplegic, and unable to continue in his occupation as a mechanic and welder.

After rehab, he applied to go to school to retrain as a social worker. AISH regulations at the time only permitted him to attend school part time. “Their thinking was that if I was well enough to go to school full time,” he recalls, “I was well enough to get a job instead.”

Seemingly arbitrary regulations like this were the catalyst for the class action suit. Curtis Roth of Tofield, Alberta, was one of the lead plaintiffs. According to his affidavit, AISH told him in 1996 that his monthly AISH payments to “top up” his CPP–D (Canada Pension Plan–Disability) benefits were too low and would be increased. But then the province started overpaying him. Four years later, after discovering its second mistake, AISH told Roth he would need to pay back the $16,000 extra he’d been given. At one point, his AISH benefits were reduced to $40 a month. “It made me very angry that a debt had been created for me, at no fault of my own,” he told the CBC at the time. “It was just a matter of an administrative error.”

Opposition MLAs say that progress is too slow. “Even at $1,050 per month, they [were] still five years behind.”

Carol Fitfield of Tees, Alberta, has multiple sclerosis. Her husband, Donald Fitfield, who is an amputee and has a fused spine, was the other lead plaintiff in the suit. Her response was more emotional. She told CBC that when she heard about the settlement, “I was crying, because I have probably 35 years of anger, disillusionment, probably hate, in me for what they’ve done to us over many, many years.”

As part of the settlement, the province paid Roth and Fitfield $5,000 each for their role in bringing the class action. Edmonton lawyer Philip Tinkler, who represented the claimants in the lawsuit, said that the province never admitted liability and that months of negotiations were “far from easy.” Meanwhile, the settlement provided a $1-million payment to the plaintiffs’ legal counsel.

Though the new AISH legislation came into effect a little more than a year after the lawsuit, MLA Rob Lougheed denies there was any causal relationship. “The new legislation was already in the works,” he says, pointing to the 2002 Disability Strategy and the 2004 MLA Task Force.

Various members of the disability communities credit Lougheed and a couple of other Conservative MLAs (Yvonne Fritz and Alana DeLong) with working persistently, and with little fanfare, to improve provincial disability policies and benefits.

Opposition MLAs say that progress is much too slow. “Even at $1,050, they [were] still five years behind,” says Lethbridge-East MLA Bridget Pastoor, Liberal shadow minister for seniors and community supports. Outraged that MLAs’ salaries are indexed but AISH payments are not, she publicly pledged to donate half of her 4.9 per cent annual increase to charities that serve AISH recipients. “Now I give $146.25 to a food bank every month.”

According to Ron Kneebone, economics professor at the University of Calgary, the 2007 benefit of $1,050 a month was actually lower in purchasing power than $850 was in 1993. “If we wanted to keep the payout at the same value that it was in 1993,” he says, “it would have to be $1,172. And that was only 70 per cent of the low income cut-off.”

Denise Young, on staff at Calgary Scope, likes the recommendation from the Low Income Working Group that AISH payments should be set at three times the average rent in any location. “Experts recommend people should pay one third of their income for rent,” she says. “The Real Estate Board calculates the average rent for a bachelor apartment in Calgary is $600. So AISH payments for a single person here would

be $1,800.”

However, Carla Kolke of Alberta Seniors & Community Supports vigorously defends the AISH benefit level in an e-mail, pointing out that, in addition to the monthly cash payment, clients receive comprehensive health services “worth an average of $322 per month per client.” She maintains that “AISH is one of the most generous programs of its kind in the country.”

Mike Hambly echoes that sentiment at the Calgary Scope dinner. “It’s one of the best programs in Canada,” he says, “but it doesn’t keep up with the economy.” Far from looking for a free ride, he says, most of his clients want what everyone else wants: a nice place to live, a family, a social life and a job that makes them feel like they’re contributing to society. Subsistence living isn’t easy. It wears people down. “Everything,” he says with a sigh, “everything is a fight.” #

Penney Kome is an award-winning journalist and author.