When Arthur Penn acquired the screenplay rights to the novel Little Big Man from Marlon Brando in the late 1960s, he also acquired the near impossibility of making it into a movie. The book, written by Thomas Berger and published in 1964, presented a big problem for Americans by muddying their glorified saga of Custer’s Last Stand at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 with the violence and senseless massacre of innocent Native Americans, many of them women and children.

Told through the eyes of Jack Crabb, the oldest living white survivor of the massacre, who had been raised by the Cheyenne, the story meanders between the two very different cultures and reveals the unchronicled hypocrisy and cruelty of western settlement from a Native American perspective. Crabb conveys admiration for the Cheyenne languages, their spiritual beliefs and their gentle, dying way of life, rooted in the relationship between all living things and depicted as much more honourable than white-centric myths of their own nobility in the classic Western.

A prolific and genre-breaking director, Penn saw his star rise steadily through the 1960s. He was part of a tsunami of young directors such as Francis Ford Coppola, Richard Donner, Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese who ushered in New Hollywood with films made on location and heavily reliant upon realism. These films addressed shifting social values and the unprecedented political upheaval of the times, using the directors’ own opinions as an agent of change.

Penn’s 1967 movie Bonnie and Clyde, the iconic saga of a pair of glamourized criminals and their adventures on the lam during the Depression, changed Hollywood forever. The film condemns the horrific atrocities carried out by Americans during the Vietnam War by introducing graphic and gratuitous violence to movie-making with what The New Yorker called a “frightening power.”

His 1969 movie Alice’s Restaurant highlighted the absurd attempts to persecute and prosecute a group of hippies during their communal Thanksgiving dinner in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Penn received Best Director nominations from the Academy Awards for both movies.

In Little Big Man Penn saw an opportunity to make a movie that revised the typical Western narrative and its glorified white heroes. To examine the history of racism in North America. “American cinema has continually parodied and ridiculed native Indians, depicting them as savage beasts in order to justify the fact that we wiped them out,” Penn said in a 1971 interview. “A mythic and heroic account of the settling of the West might ease some people’s consciences, but I’m having none of it.”

Penn could have made any film he wanted. But every time he found a studio executive willing to greenlight the movie, Little Big Man was sabotaged by unrealistic “false” budgets that would doom the project before production even started. When he finally asked why, he was told: “You can’t treat Indians this way. They gotta be the bad guys.”

Indians weren’t always the bad guys. In the first Westerns, they were most often portrayed as noble savages, primitive people of the Old West wilderness uncorrupted by the trappings of civilization. When legendary filmmaker Thomas Ince, today known as “the father of the Western,” started making motion pictures in 1909, his dramas, comedies, farces and “social problem” movies explored the stories of his times, from cosmopolitan foppery to the merciless march to conquer the wilderness. Ince was obsessed with realism, the radical art of reflecting the world back to movie audiences using natural landscapes to convey settings and characters that embodied the truth of the human condition.

Most of his one- and two-reelers chronicled cagey varmints who bastardize tiny white outposts with their unsavoury ways, lurking along rough-hewn train tracks splayed across the prairies, ready to snatch supplies destined for the hardy pioneers. Occasionally they encounter mystical savages who inhabit the land they’ve come to take, who sometimes help catch the varmints.

A small number of Ince’s films strayed from the noble savage trope to examine the inherent violence of colonization, such as Blazing the Trail (1912), a gory saga of the attacking of a wagon train moving west by “treacherous Indians.” In what has become a standard Western plot device, a young white girl is captured and whisked back to their camp, where she is tortured “by the squaws.”

As Ince flourished, he moved away from directing and began producing, attracting talented young directors (most in their late teens or early twenties and most of them now acclaimed film pioneers) such as Frank Borzage, Reginald Barker, Lynn Reynolds, John Ford and Burton George.

The Western didn’t really become the Western we know today until Ince teamed up with writer/director and all-around authentic man of the West William S. Hart, whose lone-nomad movie persona “flourished on the border, when the six-shooter was the final arbiter of all disputes between man and man,” and who single-handedly and with burlesque-like flair eradicated any hostiles who got in his way.

Their simplistic plots were increasingly coloured with the racism infecting American society, both through government attitudes, agendas and treatment of Native Americans and in the powerful potboiler literature that romanticized and lionized white settlement of the West. In what became the dominant, white-reconstructed narrative of Westerns, noble settlers were brutalized and murdered by hostile and savage Indians as they fought to take and civilize the land for the good and glory of all.

As studios began making their money by churning out formulaic movies en masse, filmmaking was caught in a struggle between artistry and profit. Realism was viewed as too expensive to be feasible, and not necessary.

Ince’s disillusionment with the Western genre became more racist, and he flew against convention by creating Triangle Films with Mack Sennett and D.W. Griffith. He and his stable of young comers made feature-length dramas, Westerns—and an Alberta-specific genre of the Western known as NorWesters (short for Northwest melodramas), which were lavish, artistic, technically masterful and rooted in realism.

Like Westerns, NorWesters were survival dramas set in the last wilderness frontier on the continent at the time—Alberta, which was being heavily promoted as such in government settlement and tourism campaigns. As American landscapes became increasingly depleted by industrialization, Alberta became the embodiment of a mythical God’s country, a Great North Woods, where man and beast lived in beautiful harmony amid the natural powers and wonders of the vast wilderness.

Most early NorWesters were shot against California landscapes around Los Angeles that replicated the Canadian Rockies. But in 1917, in his “search for the natural,” one of Triangle’s youngest directors, Frank Borzage, headed to the Stoney Nakoda reserve at Morley, just west of Calgary, to shoot several authentic scenes of the real northwest for a “tragedy of the land of snows,” Until They Get Me.

The Stoney Nakoda are the only Indigenous people in North America who have a lasting cinematic record of their traditional way of life and culture as it changed over the last century. They have worked with some of the biggest directors of all time, including Penn and Borzage, but also Kevin Costner, Robert Altman, Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Edward Zwick, Raoul Walsh and Walt Disney.

Many movies filmed in Alberta feature Stoney Nakoda involvement as film professionals—actors, musicians, crew members, cultural consultants, mountain guides, location scouts and horse wranglers. These people often speak their own language in the films, a rare indication of the unique relationships and underlying respect from filmmakers coming to this small reserve at the foot of the Canadian Rockies.

Morley lies on a tract of barren, beautiful land between the plains and mountains, with long, sweeping expanses of grassland that rise through foothills to the majestic mountains on the western horizon, perfect for long shots and super-saturated with the cinematic realism Ince and his filmmaker were so obsessed with. The luminescent quality and drama of the natural light on the reserve is particularly exquisite.

Two very different stories of white settlement exist in North America: the sunny, bloody history in the US, and the less violent though just as oppressive confiscation of Indigenous lands

in Canada.

Most movies filmed in Alberta over the next 40 years were variations of the second, marking a return to the noble savage trope, with Indians as heroes or helpful cohorts of white heroes as they struggled to tame the unforgiving wilderness. In Frank Borzage’s 1922 film The Valley of the Silent Men, the Nakoda are filmed in their own clothes and tipis, helping a Mountie find a varmint in the wilderness. The Blood tribes of southern Alberta, once the fearsome, powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, rescue a train being robbed by varmints in Cameron of the Royal Mounted (1921), despite being vilified and accused of the robbery.

As the decades passed, however, Westerns became more racist and many clichés about Indigenous peoples became embedded in American culture with a force that remains almost unmovable. Movies such as Canadian Pacific (1949), filmed on the Morley reserve with Randolph Scott, and the extravagant remake of the Mountie classic Rose Marie, filmed in Jasper in 1953, have appalling displays of gonzo racism and the objectification and sexualization of Indigenous women, leaving horrific ramifications of murder, genocide, rape and disposability to white men for Indigenous cultures that continue today.

But the summer of 1953 also marked change in Hollywood, a very slow shifting from old to new. Westerns in particular were conservative, formulaic, racist and problematic, unappealing to the young hipsters and beatniks bursting out of the suburbs and redefining normal. Two movies shot in Alberta in 1953—Saskatchewan, by director Raoul Walsh, and The Far Country, by Anthony Mann—both a blend of Western and NorWester, helped take the genre from an undeviating glorification of the Old West to a genre that revealed the racism and psychological conflict and trauma inherent in that narrative.

John Ford’s The Searchers, filmed in part at Elk Island National Park in the cold March of 1955, created an even more powerful, unsentimental look back. It gives disturbing insight into the permanent, personal and psychological scarring that resulted from the gruesome struggle to settle the American west and expropriate the lands of a people who had lived and flourished there for thousands of years. In The Searchers there is no single hero but two: a white man, played by John Wayne, and a Comanche chief, each battling with horrifying resolve to preserve their people.

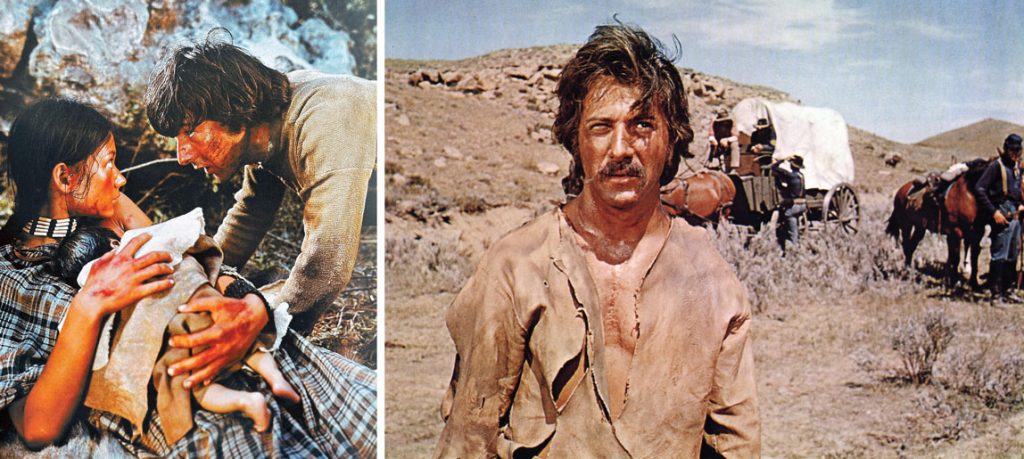

As the 1960s ended, Arthur Penn, like Ince before him, was searching for realism. He wanted to film Little Big Man, the first and most important revisionist, or post-classical, Western in authentic settings with authentic people. Production finally began in July in southern Montana, with battle scenes shot on the Crow reservation beside the Little Bighorn River. Scenes were also shot in Billings, Montana, where the city’s merchants celebrated the filming with “Little Big Man sidewalk sales.”

Penn again used his movie to denounce the horrific violence of the Vietnam war and drew parallels between the massacre of innocent civilians in Mỹ Lai in 1968 and the slaughter of American natives by Custer and his troops at the battle of Little Bighorn.

At some point he decided to shoot on the Morley reserve and with Nakoda actors, because he wanted the superabundance of the naturalism in Alberta landscapes that had attracted so many major directors here. Production of Little Big Man moved to Alberta in the bitterly cold early days of January 1970. Parts of the horrific massacre were shot at “The Bend in the River” on the banks of the Bow in Morley, a location Hollywood has now been using for a century.

In 2015 and 2016 I undertook a communal project with 15 Nakoda Elders, the Stoney Film Project, to capture the community’s largely uncredited history in film and its importance to the industry. When we watched Little Big Man, Elders Clarice Kootenay and Kathleen Poucette said they felt traumatized by the massacre scene.

Their then-15-year-old sister Cecelia Kootenay had played one of Dustin Hoffman’s young wives, who “copulated” with Crabb in a tipi before the massacre (both actors wore nude body suits). Kootenay and Poucette recall how Cecelia (who is no longer living) was always dancing and singing around the living room of their tiny house on the reserve. Their mother had taken Cecelia to Hollywood to film the scene; she remembers being impressed with the respect shown them both at the studio.

Great Chief Old Lodge Skins, the hero in Little Big Man, is played by Salish Chief Dan George. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote in his review that the Chief’s gentle and frequent use of the simple phrase “human beings” evoked a rare empathy and reflection in audiences. “Most movie Indians have had to express themselves with an ‘um’ at the end of every other word: ‘Swap-um wampum plenty soon’ etc. The Indians in Little Big Man have dialogue reflecting the idiomatic richness of Indian tongues; when Old Lodge Skins simply refers to Cheyennes as ‘the Human Beings,’ the phrase is literal and meaningful and we don’t laugh.”

Little Big Man, which Time called “a new western to begin all westerns,” left a powerful legacy. Major filmmakers, many the vanguard of the American New Wave, soon followed Penn to Alberta, as others had followed Borzage in the 1920s, many to make their own films that reconstructed the Western.

Robert Altman came to the Morley reserve in 1976 to film Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson entirely at the rodeo grounds, with a Nakoda cast, saying he wanted to “stay close to truth and far from myth.” Paul Newman, as Buffalo Bill, is an unhinged egomaniac, driven mad by his quest for power and money. He is constantly upstaged by the stoic, intelligent and artful Sitting Bull, played by Nakoda Chief Frank Kaquitts.

An even more damning examination of western settlement and white self-glorification than Little Big Man, Buffalo Bill was not well received. White viewers were not ready to see themselves this way, to have their heroes appear so openly deranged and ignoble—damagers, not the damaged. “I hope everyone left their grenades at the door,” Newman remarked to reporters in New York after the movie’s cold reception at its first screening. He added: “I don’t think there’s an audience for any kind of pain in this country.”

In 1978 Terrence Malick shot Days of Heaven in southern Alberta, using glorious fields of wheat to elevate the old NorWester into a poetic, beauty-filled homage to the early directors who filmed in the province. In the movie, realism and naturalism come alive in a mystical other-realm. Even the magic hour—the mythical, uber-cinematic light that cracks through the Alberta sky for brief moments at dawn and dusk—is a character in the movie, a flash of time when nature is most enchanting and people more bewitching and alive. Like many of the earliest NorWesters by Borzage and Reginald Barker, Days of Heaven is a story of survival in an increasingly industrialized world, the plot secondary to the visuals.

Perhaps the most brutal version of the NorWesters shot in Alberta is the 2015 survival/revenge film The Revenant, made by Mexican director Alejandro G. Iñárritu. It stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Hugh Glass, an undying fur trapper who endures against the power of the natural world and the odious realm of men. Like Crabb in Little Big Man, Glass moves between white and Indigenous worlds. Crabb takes an Indigenous wife, who with their baby is massacred by Custer and his men. Glass has a Pawnee wife who is massacred by Metis fur trappers, his surviving son murdered by a repulsive trapper whom Glass had saved in a Pawnee attack. The Alberta scenes were again filmed at “The Bend in the River” at Morley, now known to Hollywood as “Revenant Flats.”

Realism dominates the action, moods, visual magnificence and movement in the movie. It is almost a masterpiece. During the Stoney Film Project, one Nakoda Elder told me Iñárritu had insisted that Nakoda extras be smeared with a foul-smelling mixture of dirt and mud. When the Elder protested, saying his people were not a dirty people, the director replied: “History says you were.”

Mary Graham is the author of A Stunning Backdrop: Alberta in the Movies, 1917–1960 (University Calgary Press, 2022).

____________________________________________

Support independent local media. Please click to subscribe.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]