by Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

with Sabina Trimble and Peter Fortna

University of Calgary Press

2024/$34.99/352 pp.

Canada has a tragic and shameful history of evicting Indigenous Peoples from their homelands when national parks were carved out of their territory. Wood Buffalo National Park (WBNP) is the largest such park in Canada, encompassing nearly 45,000 km2. Created in 1922, it led to the expulsion and exclusion of Dënesųłıné (Dene) Peoples from their land. Remembering Our Relations centres on the oral histories of Dënesųłıné Elders, taking their experiences and knowledge seriously, and exposing the traumatic intergenerational harm of WBNP and how the creation, expansion and management of the park violated their Treaty 8 rights to their territories. The book demonstrates that Elders retain deep and detailed knowledge and interpretations of events, experiences and promises that were never included in or were erased from the documentary record. It also demonstrates their strength and resilience.

Drawing on dozens of interviews completed over several decades, the book is not just a community “engaged” history, it is a community–directed history. Willow Springs Strategic Solutions historians Peter Fortna and Sabina Trimble worked with the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN) and that community planned and conceived the project, developed the research plan and worked on the manuscript at every stage.

WBNP spans the boundaries of Alberta and the Northwest Territories and contains vast forests, wetlands, grasslands, salt plains and boreal plains. It houses the Peace–Athabasca Delta, the world’s largest inland boreal delta and second-largest freshwater delta. It is home to multiple species of waterbirds, fish and mammals. This abundant area was the traditional territory of at least 11 Dene, Métis and Cree communities. The ACFN is one of these, and their oral history and the archaeological record indicate they thrived for thousands of years here—until the park was founded.

The federal objective for the park was to preserve the last remaining wood bison herd. In 1926 over 6,500 plains buffalo were brought in and the park expanded, absorbing land the ACFN had lived on and harvested from for generations. Initially the Treaty 8 Peoples were permitted to live and harvest in the park, but after the expansion a permitting system regulated access and harvesting laws were introduced. Dene access to the park was eroded and restricted and people were evicted from their homes. In some cases wardens burned their cabins. People faced severe hardship and even starvation. Over decades, park officials repeatedly ignored attempts by the Dene to assert their rights. Racist rhetoric about Indigenous harvesters was deployed to justify their exclusion and eviction. But contrary to settler stereotypes, as the book demonstrates, responsible stewardship practices were at the heart of Dene legal systems and social worlds.

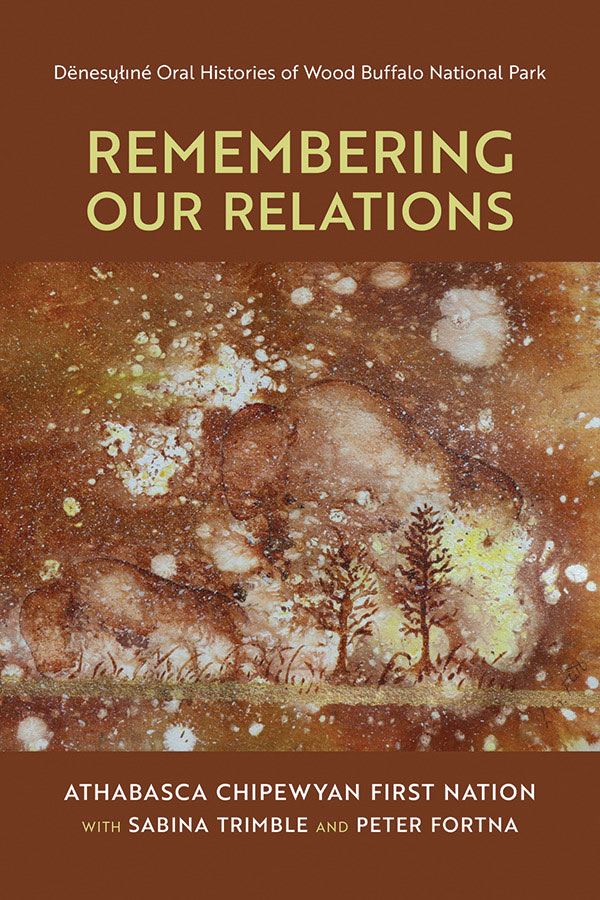

Important features of the book include a review of the scholarship on national parks that displaced, excluded and impoverished Indigenous Peoples in Canada. This is situated within a global pattern of settler colonial work to advance control over Indigenous land and resources. Yet we learn that the creation of WBNP is distinct in several ways, as here settler hunting and tourism were not central priorities, and some Indigenous harvesting was allowed within park boundaries. There is a useful appendix on building a community-directed work of oral history, and digital copies of archival documents can be viewed by scanning the QR codes. Links to the voices of the Elders themselves, some in Dene, are also provided through QR codes. Excellent maps and stunning photographs both historic and recent are included, though I wished some were in colour. Overall, this is an important book that Albertans should read and reflect on.

Sarah Carter is a professor in the department of history, classics and religion at the University of Alberta.

_______________________________________