In 1875 the Northwest Mounted Police, dispatched south from Fort Edmonton to roust American whisky traders, arrived at Nose Hill and looked down on a green valley at the edge of the foothills. Below them they could see where the trail converged with a ford where the floodplain of the smaller Elbow River blocked and widened the larger Bow.

Sergeant G. King, one of that party, later wrote: “When we… looked down upon the valley which is now the City of Calgary, it looked like a veritable paradise; large, leafy trees lined both sides of the Bow and Elbow rivers, there was a profusion of flowers, grass was knee deep, and from Mount Royal to what is now 13th Avenue was one huge lake. I thought, at the time, it was the most beautiful spot I had ever seen.”

Centuries of gravel and cobbles, deposited by that meeting of the rivers, had accumulated on a broad floodplain marked by abandoned stream channels, wetlands and brush thickets. King’s “lake” was an immense beaver pond. The rodents had dammed the Elbow River a little ways upstream from its confluence with the Bow. The dam soon blew out in a spring flood, but the pond must have been lovely while it lasted.

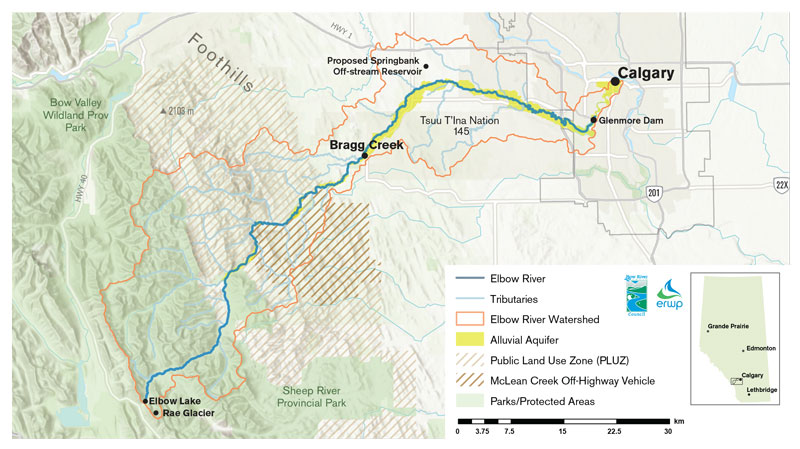

The Elbow River valley must have been lovely too. Parts still are. The river’s headwaters, in particular, retain much of their original beauty. The river rises from an idyllic mountain tarn, Elbow Lake, which is fed in part by meltwaters from Rae Glacier. Downstream from the lake, the newborn Elbow tumbles through willow flats and pine forests. As it follows its winding way through the Front Ranges of the Rockies it picks up tributary streams—the Little Elbow River, Cougar Creek, Ford, Prairie, Quirk, Canyon, Bragg and others.

“View from hill near Fort Calgary,” an illustration by the Marquess of Lorne (John Campbell), ca. 1882, in Picturesque Canada.

Each creek adds to the river’s volume, but most of its growth comes from what hydrologists call “base flow”—groundwater emerging into the riverbed itself. In fact, the largest part of the river is underground, in its alluvial aquifer, the hidden part of the river that connects to all the secret groundwater flows that seep through the mountain and foothills landscape.

By the time the river plunges over Elbow Falls, near Bragg Creek, it’s become a substantial stream, at least by Alberta standards, and its water is cold, clear and reliable. Calgary politicians, in the early years of the 20th century, briefly proposed running pipelines up to the headwaters to capture that good water.

Because the Bow and Elbow rivers are subject to spring floods, however, the young city was continually plagued with flooded streets and muddy water lines during spring and a shrunken stream by late summer and fall. Engineers chose to deal with the growing city’s water challenges by damming the river just outside Calgary’s boundaries. The Glenmore Dam, completed in late 1932, provided both a storage reservoir for the growing city and greater protection against flooding.

That latter was important, because Calgary built its city core and its earliest neighbourhoods right on the floodplain of the Bow and Elbow rivers. Sergeant King’s beaver pond should have given them a clue that this was a bad idea. Even so, one of the worst floods in the city’s history occurred that spring of 1932 when the dam was nearing completion, and it proved its worth by keeping many downstream streets from being drowned. And so the city continued to develop its floodplain.

The city grew outwards, too. It soon surrounded and, by the 1980s, extended well west of the Glenmore reservoir. Much of the new development was on the alluvial aquifer and the floodplain—essentially in the river, just like the oldest Calgary neighbourhoods. As the river’s valley and watershed changed, more mud and pollutants flowed to the river and its groundwater feeds became increasingly disrupted. But shrunken and degraded though it might be, the Elbow’s diminished waters still flow through Calgary’s shade-dappled floodplain neighbourhoods and so its slow death goes largely unremarked—except during floods.

Flora Giesbrecht is the Coordinator for the Elbow River Watershed Partnership, one of several watershed councils in Alberta established to bring stakeholders and communities together in studying and conserving their water supplies. The undertaking demands a lot of diplomacy, because many of the partners in those groups are heavily invested in the very land uses and industries that put the most strain on water resources.

“The river is a reflection of our landscape,” says Giesbrecht, when asked what’s needed to restore and sustain the health of the Elbow. “People need to acknowledge that land uses can affect water, both its quantity and its quality. Most of us don’t see the connection between land and water. At the least, we need to minimize whenever possible any new development in the alluvial aquifer.”

Alluvial aquifers generally lie beneath the floodplains of gravel-bed rivers like the Elbow, although they can wander where buried river channels offer paths of low resistance. The river and its aquifer are intimately connected, which is why Giesbrecht’s organization is so concerned about development on that part of the landscape.

Giesbrecht points to research by Cathy Ryan, a hydrologist at the University of Calgary who has directed several studies of the Elbow watershed. “Due to rapid population growth and a desire from citizens to live close to the Elbow, the watershed has been subjected to substantial pressures for development, especially concentrating along the alluvial aquifer which surrounds the river,” according to one study completed by Ryan’s students. “The alluvial aquifer… is very permeable and hydraulically connected to the Elbow River and is characterized by significant groundwater to surface-water exchange.”

Rae Glacier, whose fate is both a metaphor for what’s happening to the Elbow River itself and a warning of worse things yet to come.

The part of the alluvial aquifer that lies under the modern river’s floodplain is where the river’s heart beats, but it’s a heartbeat so slow and secret that few of us perceive it. In spring, when snowmelt and rain in the upstream watershed exceeds the ability of the ground to soak it all up, the river floods and pushes water out across its floodplain, into the poplar and willow forests, grassy flats and wetlands. That water soaks into the gravel beneath. Then, in summer, when the river shrinks, the stored water drains slowly back into the channel, keeping the river filled. Like a slow annual heartbeat, it all happens out of sight, which is why developers and other land users have traditionally ignored it. But it’s a big part of what keeps rivers and their ecosystems healthy.

Along the Elbow—as along most Alberta rivers—development is slowly choking that heartbeat. And where such development takes place along the floodplain, flooding ceases to be a natural phenomenon we watch in awe from the valley rim and increasingly becomes a threat to the things we built. The response: flood protections such as bulldozed berms and bank armouring with boulders that further choke the river’s heartbeat and, ironically, drive even greater flood risk downstream. Upstream from Calgary, where the provincial government is now poised to build a massive Springbank dry reservoir in an effort to protect the city from floods, developers continue to squeeze the river between engineered flood-protection berms to keep new developments safe. More than 13 kilometres of Elbow river bank are now bermed or otherwise modified, stealing the ability of the floodplain to hold back spring flows and instead turning the river into a firehose pointing downstream towards Calgary.

Left: Elbow Lake. Local climate models project less winter snow and more rain, which runs off frozen ground instead of being stored as snowpack. Right: The upper Elbow River.

Ryan’s research teams studied land use trends to predict the future for the Elbow River, and the results are cause for concern. While 37 years ago only 16 per cent of the Elbow’s critically important aquifer had been developed for real estate, the study found that today almost a third of it has been developed. Real estate speculators now own half the land on the aquifer upstream of the city, a grim portent for its future.

Development on the aquifer creates a set of interrelated water risks for downstream ecosystems and communities. Septic fields, fertilizers, pesticides and livestock waste increasingly contaminate groundwater, which inevitably pollutes the river; it’s the same water, after all. And the pollution doesn’t just happen underground, either: buildings, roads and other hardened surfaces stop rainwater from soaking into the ground and instead send it down ditches and gullies to the river, carrying eroded mud, manure and other contaminants. The water that runs off rapidly during the spring rains also adds to downstream flooding risk.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Hydrology projected a 65 per cent increase in developed areas over the Elbow watershed as a whole, slight increases in rangeland and parkland, and loss of up to a quarter of its forest cover by 2032. The authors project a 7 per cent increase in water runoff and a 13.2 per cent reduction in groundwater flow into the river, which they describe as a “…significant negative impact on the sustainability of ground/surface water supplies and groundwater storages in the future… in addition to an increased risk of flashy floods.”

The water in the river and its alluvial aquifer originates as winter snowpack and spring rains, so the health of the headwaters landscape is every bit as important to the river as the protection of its floodplain. Fortunately for the Elbow, real estate development poses little threat to its headwaters. Unfortunately, however, other problems arise there.

The river headwaters are public land, part of the popular Kananaskis Country. While some of the area—including Elbow Lake—is protected in wildland parks, most is in the Spray Lakes Sawmills forest management area, dedicated to commercial logging. Parts have been aggressively clear-cut in recent years, including the whole length of Quirk Creek, areas around Bragg Creek, and the McLean Creek drainage. Monitoring studies have shown that large-scale logging operations increase spring runoff and erosion by accumulating deeper snowpacks that, without shade from the missing canopy, melt rapidly in spring. That means more severe flooding and less base flow in the rivers later on.

The McLean Creek drainage, however, has bigger problems than just logging. It is designated a Public Land Use Zone, reserved for motorized off-road play. Entire hillsides are denuded of soil, once-vegetated seismic cutlines are deeply gullied, wetlands are churned to mud and the creek itself is silted and flood-prone because of the many hundreds of erosion channels draining into it. Some of the worst damage from Alberta’s 2013 flood originated there.

Climate change is a serious threat to rivers like the Elbow, because most climate models project less winter snow and more rain.

Giesbrecht says some improvements have been made since that flood; for example, recovery funding was directed towards trail improvements and better bridges. But she says the problem is ongoing because many users don’t know which trails are legitimate and what the rules are. “People see routes and follow them. There’s a lot of confusion. It just takes one vehicle track and people follow it, and accidental trails become permanent.”

All the silt and pollution flushed out of the McLean Creek “sacrifice area” and the increasing number of clear-cuts and roads in the upper Elbow watershed ends up in Calgary’s Glenmore reservoir, which supplies drinking water to more than a half million Calgarians. There, this gunk both shortens the life of the reservoir by filling it with sediment and increases the costs of water treatment. Rapid runoff from damaged land also increases the severity of spring floods.

The Elbow River in Calgary. Berms combined with excessive spring flows can turn the river into a firehose pointing downstream toward the city.

Nobody knows how much of the damage caused by the 2013 flood might have been avoided if the Elbow River’s watershed had been more intact. Nobody has studied that. Researchers look at discrete, measurable questions relating to one part of a landscape or another. Foresters point out that they only log part of the headwaters and that modern planning and forestry practices reduce the harm they cause, brushing aside valid criticism of the effects that their large clear-cuts and hardened forest roads continue to have on runoff patterns. Off-road recreation advocates bridle at any suggestion that their machines cause harm, insisting that most users are “responsible”—as if that makes any difference when the rains pound down on countless kilometres of hardened soil trails. Developers plant cattails around storm-sewer ponds and boast of green development, ignoring both the flood risk to which they are exposing their customers and the strain they add to the river’s alluvial heartbeat. Each sector of society carves up their part of the watershed and points fingers of blame at the others.

The Elbow River watershed partnership is one of the few organizations looking at the cumulative effects of all land uses. It recently completed the second “State of the Watershed” report for the Elbow, an objective but sobering assessment of the impacts of the many land use choices we make on the water we rely on. The report reminds us of one more reason why treating land use decisions as water management choices is critically important today: the climate crisis.

Towards the end of the hot, smoky 2021 summer my wife and I parked beside the Kananaskis highway and headed up a steep trail. We picked our way along the shore of Elbow Lake and continued up a side valley, climbing steadily, until a bend in the trail revealed our destination: Rae Glacier.

Few glaciers survive in the southern Rockies. The Rae, the source of the Elbow River, is one of the last. Since our most recent visit, three years ago, we could see where the tops, sides and bottom had melted away. The glacier is now so thin that a large rock face has emerged where before it was ice.

“Temperatures were about 2 to 4 degrees above normal in July [2021],” says John Pomeroy, a hydrologist specializing in the Eastern Slopes of the Rocky Mountains. “The glaciers have been melting at two-thirds of a metre per week where we’ve been monitoring them, which is the highest rate ever. That would lead to about seven metres of downward melting over the summer.”

Rae Glacier can’t spare that much ice; it is doomed. Its fate is both a metaphor for what is happening to the river itself and a warning of worse things yet to come.

Climate change is a serious threat to rivers like the Elbow, because most local climate models project less winter snow and more rain, which runs off the frozen ground instead of remaining stored in the snowpack. The models predict more intense summer evaporation and, worse, a greater frequency of intense weather events such as the June deluge that spawned the 2013 flood and the massive heat system that accelerated glacial retreat in 2021. While there are things we can, and should, be doing to reduce the threat of climate change, that horse is well out of the barn. Even with aggressive action—which the world has not yet proven ready to embrace—the climate crisis is going to intensify.

But landscape changes can make everything worse yet. Eroding clear-cuts, gullied OHV trails, development-choked floodplains and rip-rapped river banks already send floodwaters coursing downstream too fast, while reducing the amount and quality of groundwater recharge. The damage will be significantly greater with more intense weather—as southwestern BC learned tragically this past winter. And when most of the water runs off in spring floods, the consequences during long, hotter summers become even more severe.

If water matters to our future, then river health matters. And if river health matters, then watersheds need better care. The Elbow simply cannot absorb any more development on its alluvial aquifer and floodplain; if anything, we need to start reducing development. Floodplains should be restored and then protected as natural parks. And clear-cutting and motorized abuse simply have no place in the forested headwaters of so important a river. The headwaters of vital rivers like the Elbow should probably be parks too.

The Blackfoot people know the Elbow River and the place where its waters join the Bow as Moh’kinstis. Those people had lived beside these waters, through the cycles of the seasons, amidst the beauty and abundance of this landscape, for many centuries before Sergeant King looked down from the flanks of Nose Hill and was struck by the beauty of the area. The newcomers whom King represented and the original people of this storied landscape would soon enter into a treaty relationship that set the stage for modern Alberta.

The Elbow River flows through the heart of this treaty place, but just as failure to honour that treaty relationship has created a need and a duty for reconciliation among peoples, we urgently need to reconcile our failures with the river and the lands it drains from.

Our ability to influence climate policy, at least at a global scale, is limited. But we are completely in control of land-use decisions here at home; we elect and influence the governments who make them. It’s long past time to start getting those decisions right instead of adding to the litany of cumulative effects that threaten the heartbeat and health of the Elbow and other Alberta rivers—streams that not only will determine our society’s future but amplify its failures.

Kevin Van Tighem is the author of 14 books on wildlife and conservation, including Wild Roses Are Worth It (RMB, 2021).