The rise of the right-wing, authoritarian populist movements across the Western world owes much to the support of rural citizens who are increasingly feeling left behind economically and culturally and are eager to overturn the status quo. I’ve been thinking about the plight of rural Alberta in this context, partly from the perspective of a political scientist but mostly as a rural Albertan myself, concerned for the region’s future and curious about how my fellow rural Albertans are making sense of politics in a time when many of them, and their communities, are struggling.

Prior to the pandemic, I did an ethnographic study to address this curiosity. For the sake of simplicity, I assumed rural Alberta constitutes those areas beyond the province’s largest cities: Edmonton, Calgary, Red Deer, Lethbridge, Grande Prairie, Fort McMurray and Medicine Hat and their corresponding bedroom communities. Following the lead of American political scientist Katherine Cramer, I immersed myself in the regular conversations of 23 groups of acquaintances in 16 communities throughout rural Alberta. I showed up at cafes and restaurants, I joined groups of young families in their living rooms or on their front decks, I met with women’s-only coffee groups, I shared a case of Pilsner with a rural men’s baseball team. All told I spoke with 138 rural Albertans about politics in conversations that lasted anywhere from 45 minutes to three hours.

Over the course of this exercise I heard a few good jokes, more than a few phrases in Ukrainian, one heated debate over a game-deciding measurement in the town curling bonspiel, and, I’m afraid to say, startlingly high levels of political anger and resentment. Rural Alberta is far from a homogeneous region, and many issues unique to particular towns were raised. But on the whole, a high degree of agreement exists on three particular points.

Many rural Albertans feel a visceral anger toward Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government, largely placing the blame for Alberta’s current fiscal woes at its feet. This is unsurprising—Premier Jason Kenney has been fanning this sentiment for some time. But more interestingly, rural Albertans are also increasingly disillusioned with politics in general, expressing widespread scorn at the behaviour of politicians and parties of all stripes (many wistfully imagining a politics completely free of parties, which, according to a coffee group in Fort Macleod, “just sour everything”) and strongly convinced that existing parties don’t care about “ordinary people.” Finally, many in rural Alberta are increasingly convinced they are unfairly treated, overlooked and even looked down upon by urban citizens and “their” governments.

An exchange in a McDonalds in Drayton Valley strongly encapsulated this particular view, which emerged again and again across the groups I met. Asked if people in cities understand rural areas or their struggles, one resident nearly jumped out of his seat: “Absolutely not! We might as well be from different planets. And the government workers, the politicians, the professors from Edmonton? They’re the worst… they simply don’t understand what it’s really like out here.” Added his coffee companion, “Most of [them] see us as rednecks who can barely get our pants on by ourselves. I don’t have a college degree, so I’m an idiot. That’s what they’re thinking. I worked from nothing to a senior management position in an oil company. But I’ll always be a redneck in their eyes.” His wife chimed in, “Oh, yes, they think we’re rednecks… It’s nice that you came out here. Nice that someone wants to listen. Do you think anyone will listen to what you write?”

Overall, a growing anti-establishment sentiment tied to this resentment was evident, a desire for some type of upheaval to address these concerns. This is certainly not new. I’d argue a good deal of rural support for the Wildrose party over the past decade was driven moreso by this underlying alienation and a corresponding populist desire to “throw the bums out” than by hard-right ideology. For some in rural Alberta today, this translates into support for “Wexit.” But it’s not difficult to imagine such resentment being exploited for even more troublesome and divisive ends. Not only did most rural citizens I chatted with express a strong admiration for Donald Trump (“someone who’s finally listening to ordinary people for a change!” declared a woman from Westlock), some also linked their own frustrations, their own sense of being overlooked, with a palpable resentment aimed at refugees and especially Indigenous peoples, who are viewed as the chief beneficiaries of exorbitant state support. In an age of increasing polarization, misinformation and, in many cases, tribalism and xenophobia, the potential exploitation of this resentment most worries me.

In the context of contemporary Alberta politics, in which the United Conservative Party government unveils policies that don’t serve rural Alberta well, I’m left wondering how this alienation and resentment can be addressed. How can this region be authentically represented?

The notion that rural Albertans aren’t adequately represented in provincial politics likely strikes most readers as absurd. Rural support forms the backbone of the UCP. In the 2019 election the UCP garnered well over 70 per cent of the votes cast across rural Alberta, easily sweeping every rural seat and ensuring several rural MLAs have prominent roles in cabinet. And this is par for the course in Alberta. Aside from a few blips (perhaps the first term of Peter Lougheed’s government, the relatively short reign of Alison Redford, and the recent single term of the NDP), rural Alberta has formed the electoral base of basically every Alberta government going back to 1905. Likely no constituency in Canada has been so closely connected to political power for such a long stretch.

For much of this time rural Alberta reaped many benefits. The UFA and Social Credit governments clearly focused on rural regions, the latter spending massively on rural infrastructure throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The PC party under both Lougheed and Don Getty followed suit, using resource-padded coffers to build roads, schools, hospitals, hockey rinks and seniors lodges across rural areas while also supporting a variety of loan programs and subsidies for farmers, ensuring grants flowed to rural community and agricultural societies, and footing the bill for more than a few community-specific projects in the constituencies of well-regarded rural cabinet ministers.

This all changed with the advent of a neoliberal approach to economic development in the 1990s, focused on deregulation and low taxes as keys to attracting investment and spurring growth. The relationship between the government and rural Alberta shifted. Few in Alberta, urban or rural, forget the impact that cutbacks in healthcare, education and infrastructure had across the province in the early years of Ralph Klein’s government. For rural Alberta in particular, these cuts, in combination with the broader changes to the economics of agriculture unleashed by neoliberal-inspired free-trade agreements, fast-tracked a decline in municipal and individual economic prospects across the region. Rural schools closed, healthcare centres either closed or reduced their offerings, multi-generation family farms were sold off, transfers to municipalities shrank and infrastructure maintenance declined, youth hightailed it to urban centres and local businesses struggled mightily.

More broadly this period represented a turning point for conservative parties across much of the western world. Suddenly the central goal was no longer “conserving” much of anything. Rather, the goal became sharply reduced tax rates and regulations to entice capital investment—an aim that created jobs (although often for low wages) but weakened the state’s ability to provide the services low-density and increasingly low-income rural areas rely on.

Of course, this shift was welcomed with open arms by the province’s resource sector, and, in an era of strong oil prices and hefty resource royalties flowing to the government, who could complain? The “Alberta Advantage” was in full swing—low taxes, low unemployment and high per-capita government spending—the holy trinity of Alberta politics. But underneath these developments in conservative ideology, this wholehearted embrace of a low-tax regime and oil and gas-friendly public policies, was the sacrifice of any coherent policy concern over the future of rural Alberta.

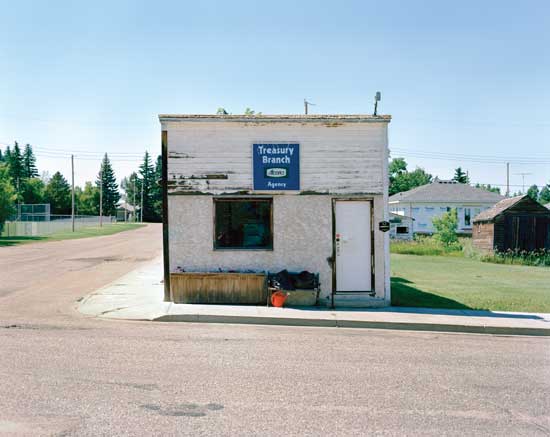

Kyler Zeleny grew up on a farm in central Alberta. He is a photographer–researcher and author of Out West (2014), Found Polaroids (2017) and Crown Ditch and The Prairie Castle (2019). Understanding the rural, he says, consumes him. Sleeping in his car, bathing in lakes, he tries to understand present-day ideas of the rural and how it has been visually represented. He has degrees from U of A and the University of London.

Since the Klein revolution, successive PC governments’ approaches to rural issues have been a mixed bag. The PCs did recommit, at least rhetorically, to the importance of rural Alberta in the last years of the Klein regime and especially under Ed Stelmach. Task forces were commissioned, reports were issued and money was spent, although these initiatives created little meaningful rural development. The Redford government did release a Rural Economic Development Action Plan in 2014, although this was derailed by the party’s historic loss in 2015.

The UCP has similarly failed to offer much in the way of a concrete rural development plan beyond its general province-wide pledge to “create jobs.” The UCP, to be fair, did announce in June 2020 a one-time $200-million allotment for rural infrastructure, although the president of the Rural Municipalities of Alberta said “hundreds of millions” more was needed to properly address the infrastructure deficit that plagues the region. In fact, several rural municipalities are considering dissolving themselves entirely in the face of infrastructure upgrades they can’t afford.

In November Premier Kenney responded to concerned rural politicians by urging them to cut “red tape” to attract investment, as if the removal of a couple of forms or a less stringent approvals process is all that stands between rural communities and a cascade of new businesses knocking down their door, the beginning of a new golden age.

Even more surprising has been the UCP’s willingness to upset a large swath of rural voters with policy decisions. Rural regions witnessed scores of doctors threaten to leave their already underserved communities over a protracted contract dispute with the UCP government. Counties are warning citizens to expect drastic property tax increases as the province offloads policing costs and seeks to significantly reduce tax rates for oil companies. Many rural voices, most notably country music singers Corb Lund and Paul Brandt, were at the forefront of public opposition to plans to allow coal mining on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

Taken together, it is increasingly difficult to see what lasting benefits rural Albertans have amassed over the last two or three decades in exchange for the rock-solid support they routinely granted conservative governments. Surely the oil and gas boom of the 2000s helped paper over much of this. Rural Albertans scooped up well-paying jobs in the industry, and companies contributed significant tax revenues for rural municipalities and extra income for farmers who had an oil or gas well on their land. But such opportunities are now few and far between, and some in the industry are refusing to pay taxes they owe rural municipalities. As of February 2021 they were over $245-million in arrears, with many companies additionally declining to honour their contracts with rural landowners.

Agriculture in Alberta does continue to generate billions of dollars of economic activity annually, although sharply declining profit margins have ensured that only the largest farms consistently reap strong returns. To make matters worse, the mega-size machinery now required by ever-growing farms is causing unforeseen, and expensive, wear to country roads.

Today the neoliberal chickens have come home to roost. Much of rural Alberta sits in a precarious position. Job opportunities are diminished, the population is rapidly aging, residents must travel farther to access schooling, healthcare and long-term care, rural students are more likely to drop out than their urban counterparts, rural infrastructure continues to deteriorate, revenue-starved municipalities are weighing drastic service cuts against significant property tax increases—while simultaneously facing the looming prospect of enormous liabilities associated with orphaned oil and gas wells—and, as the pandemic reminded us, decent and affordable internet often remains out of reach. Given the lack of interest from successive Alberta governments in authentically addressing rural issues, it’s no wonder citizens are feeling alienated and resentment is growing.

Rural Albertans routinely identify as “conservative” in opinion surveys; they vote overwhelmingly Conservative in provincial and federal elections; and in conversation they highlight fiscal prudence, self-reliance and personal discipline as characteristics they strongly value. Throughout my research, many scoffed at “political correctness,” were enraged by the salaries and pension benefits received by bureaucrats and politicians, and were very concerned with rural crime and the “soft” justice system that, in their view, condones such behaviour. Some are socially conservative, many are not. And above all, the majority do not like the NDP. This is a deep, essentially cultural, dislike.

But here is the rub. There is an important ideological disconnect between the political values of many in rural Alberta and those of the UCP, a disconnect even close observers of Alberta politics tend to overlook.

Not only have public opinion surveys shown that the majority of rural Albertans are actually “middle of the road” in their ideological leanings, I am convinced after having completed my ethnographic study (in addition to having lived in rural Alberta most of my life) that the conservatism most in rural Alberta abide by is not generally the anti-government, libertarian version that undergirds the UCP. Rather, most rural Albertans adhere to a more traditional version of conservatism that, to be sure, values fiscal discipline and self-reliance, but is also pragmatic and recognizes the value of prudent state investment in education and healthcare, in infrastructure and in sport and culture—the foundations of the healthy community institutions rural Albertans depend on. Furthermore, it is a conservatism largely built on a personal commitment to community, a willingness to volunteer and contribute to its well-being, rather than an obsession over the rights of the individual.

I have yet to hear a stampede of rural Albertans crusade for lower corporate tax rates or demand that oil and gas companies receive a property tax holiday, nor are many demanding the return of coal mining in the eastern slopes of the Rockies or the sale of gas leases on the Milk River grasslands. I have yet to hear rural Albertans argue that we have too many nurses or teachers, or too many rural hospitals or schools. I have yet to hear rural Albertans suggest that existing supports for seniors in the region are adequate, or clamour for smaller provincial transfers to municipalities or regional economic development agencies, or an end to grants for community recreation or agricultural societies. I can also report that, despite frequent suggestions to the contrary on social media, the vast majority of rural Albertans are not aghast at the “loss of their freedom” inherent in requests to wear a facemask or adhere to “stay-at-home” orders in the midst of the pandemic. Indeed, there are blatant areas of tension between the policy preferences of most rural Albertans and the policy priorities of the UCP.

Rural Albertans, it is true, tend to harbour suspicions about government. But in talking with them it became clear that the crux almost always revolves around politicians “living-it-up in expensive hotel suites, jetting around on private planes, drinking $20 orange juice,” the relatively generous salaries and benefits of civil servants in Edmonton and, for some, the sense that newcomers to Canada and Indigenous peoples receive disproportionate state support (although several rural municipalities are making positive strides on these issues, creating “Welcoming Committees,” pursuing anti-racism initiatives and adopting treaty land acknowledgements at community events).

One can legitimately question the disconnect between a desire for government services and a refusal to acknowledge the role played by civil servants in providing these services, or the inadequate understanding of “who” in fact “gets what” from government. The larger point, however, is that most rural Albertans are not simply opposed to government full stop. Rather, they resent that some groups seem to get more than their fair share, while rural areas receive the short end of the stick. This conclusion strongly echoes similar findings in rural America, where research shows resentment of this sort—rather than an ideological commitment to anti-government neoliberalism—explains such strong support for conservative politicians.

Of course, far-right libertarian voices also emanate from rural Alberta. Such people seem disproportionately to occupy positions in rural UCP constituency associations, some becoming candidates themselves.

Despite this ideological disconnect, it seems incomprehensible to imagine the UCP losing ground in rural Alberta. What gives?

Part of this is basic party identification. The UCP is now the only legit conservative party in town, a last line of defence against a return to power by the NDP. But beyond that, the UCP has done well to play to the anxieties of the region. Few in rural Alberta seem much bothered by the UCP’s desire to shrink the civil service. Nor were they opposed to the party’s repeal of the provincial carbon tax. As the unofficial spokesperson for a women’s coffee group in Tofield told me, following a lengthy conversation outlining their environmental concerns, “I have absolutely no other option. I simply have to pay more. I can’t take the bus. I can’t afford an electric car. And I couldn’t plug it in anywhere if I could. How is this anything but an extra tax on rural people?”

Paradoxically, given that corporation-friendly neoliberal policies by previous conservative governments helped put rural regions on the path to precarity in the first place, many rural Albertans view the province’s immediate prosperity, and their own, as tied directly to the revival of oil and gas. Thus, they largely applauded the UCP’s doubling down in this direction, especially Kenney’s anti-Liberal rhetoric, his Canadian Energy Centre “war room” and the “Fair Deal Panel.”

The UCP further created the Rural Alberta Provincial Integrated Defence (RAPID) Response to address rural crime, replaced the labour standards codified in the NDP’s infamous Bill 6 with the Farm Freedom and Safety Act, and established the largely symbolic Alberta Firearms Advisory Committee to “hear concerns about the federal government’s firearms legislation.”

It doesn’t take a vivid imagination to see how well such moves play throughout the region. But do any of them address the fundamental issues facing rural Alberta? Which will create long-term jobs in a global context of declining oil demand? Which will ensure that rural schools remain open, that doctors stick around, that affordable high-speed internet becomes available? Which will address the vast rural infrastructure deficit? Where, in any of this, is a coherent, consistent, evidence-based rural economic and community development plan?

Modern economic trends have clearly been unkind to rural areas worldwide. Yet rural development scholars have demonstrated that the “death of rural” is not inevitable. Real economic progress and enhanced service delivery for rural areas is possible, but at minimum it requires a long-term plan.

As Lars Hallström, who directed the Alberta Centre for Sustainable Rural Communities at the University of Alberta from 2009 to 2020, put it: “A dedication to rural sustainability should inspire thinking around the linkages that exist. The question of rural physicians and rural healthcare is connected to rural health inequities which are connected to rural social inequities which are connected to rural capital flight and the changing face of agriculture and who stays behind, the closure of rural schools etc. You have to think about all of this as a collective. But the policy response under all Alberta governments since forever has been to occasionally throw some money at rural regions without much thought to any broader development goals. How will this actually support rural communities in a sustained way?”

In tandem with an increasing sense of resentment, support for Wexit seems to be growing in rural Alberta. I suspect some smaller oil companies, eager to be free of federal restrictions, will chip in some cash to back such a venture. But perhaps rural Albertans might try something different in their quest to upend the status quo.

Rather than Wexit, imagine a rural-based provincial party emerging in Alberta, running candidates only in rural ridings and advocating, first and foremost, for the well-being of rural Alberta. A “Bloc Rural,” if you like. It would lean conservative, no doubt, but more importantly, rural would be at its core. An existing party (Alberta Party?) might support many of the same policies, but the lack of a rural core will prevent widescale buy-in. Rural identity is a powerful force outside cities.

The new party would probably support the UCP’s efforts to address rural crime, fortify property rights, shrink the salaries of Edmonton-based civil servants—whatever rural Albertans deem important. But the party would also work to ensure doctors are recruited rather than driven out of rural towns. It would advocate for an education funding model that ensures no student has to ride a bus for three hours daily. It would demand affordable high-speed internet for all, maintenance of basic infrastructure in rural municipalities, creation of a subsidized transportation network capable of delivering rural citizens to specialist medical appointments in Edmonton or Calgary. Above all, it would craft a well-designed social and economic plan that provides hope for the future.

Given the resurgence of the NDP in Alberta politics, a new party consistently occupying a large number of rural seats would make minority governments much more likely. In such a scenario, a new party could demand a meaningful policy commitment to rural Alberta in exchange for its support, improving conditions across the region. As importantly, it might help stem a growing tide of resentment in the region before it becomes destructive. And while the idea may seem unrealistic, even letting one’s mind wander in this direction could be a helpful exercise in focusing on what policies are in fact in the best interests of rural Alberta.

Clark Banack is acting director of the Alberta Centre for Sustainable Rural Communities at the Augustana Campus of the University of Alberta.

____________________________________________