For a number of years I exchanged services with youngsters in trouble with the law. The terms of our exchange weren’t clearly articulated, but in practice they are simple to describe. I offered them classes on writing and theatre. They provided resistance, recriminations, endless objections and surprisingly creative profanity. My duty was to encourage them to write scenes and plays, which they reluctantly, grudgingly, bitterly, sometimes willingly, often violently, but ultimately successfully executed. I then directed them in performances of their writing. Together we produced and turned out short plays, roughly three a year, for about two decades.

Some of the young people I worked with were in treatment for drug problems. Some were “in program” for anger management issues. For the majority of my tenure with the Wood’s Homes organization, I worked with young sex offenders. Many of them were in program as a condition of a sentence imposed by the court. It was either do treatment or do time.

My pastime often sparked the most animated and heated conversations. Civilians who weren’t familiar with the program would inform me that they didn’t know why I bothered with “that sort”—“that sort” being teens in trouble with the law, specifically teens who had committed sexual offences. The prevailing notion was that, young though they were, reforming them wasn’t really an option. Given the serious nature of their crimes, prison was what they needed, and the harder the time the better. Prison would scare them straight.

I’m thinking back to these conversations now because of the echo I detect in the federal government’s recently proposed amendments to the Youth Criminal Justice Act. Some of Minister of Justice Rob Nicholson’s goals and procedures are described on the federal government’s website.

They provided resistance, recriminations, endless objections and surprisingly creative profanity.

“The proposed sentencing amendment,” the site states, “would allow courts to consider deterrence and denunciation as objectives of youth sentences. These objectives are included in a manner consistent with the principle of proportionality, which requires that the punishment fits the crime (i.e., the more serious the crime, the more severe the sentence).” It further describes what some of the deterrent measures might look like: “…As part of its platform commitment, the Government had indicated that it would amend the YCJA to provide for automatic adult provisions for youth found guilty of serious and violent crime and repeat offences.”

It’s clear from this wording that the government believes that by imposing harsher sentences, by shifting young offenders into adult court and by applying the principle of “denunciation,” young offenders will be deterred in greater measure from committing their crimes. Well, maybe that will happen, but I have my doubts. Here’s why.

Let’s consider the young people I worked with. Generally, they’d experienced disruption in their home environments: divorces, separations, multiple guardians, dislocations. Most often, they’d experienced some kind of serious abuse over an extended period. They were—as already noted—all troubled, but that’s too vague a term, so let me try to be more specific. By “troubled” I mean to say that they experienced tremendous difficulty with both decision-making and emotional expression, and these traits impacted upon each other. Their inability to express emotions properly often played out in terrible decisions. They frightened, angered and saddened easily; raged and lashed out at people without warning. An individual in one group felt belittled when someone stole his seat during a group meeting. He responded by bloodying the person’s nose. This kind of irrational, emotional response to small matters was a signature of their behaviour.

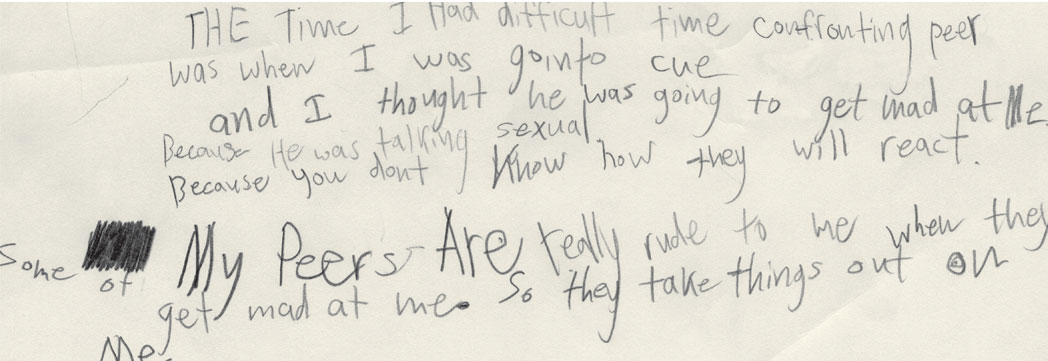

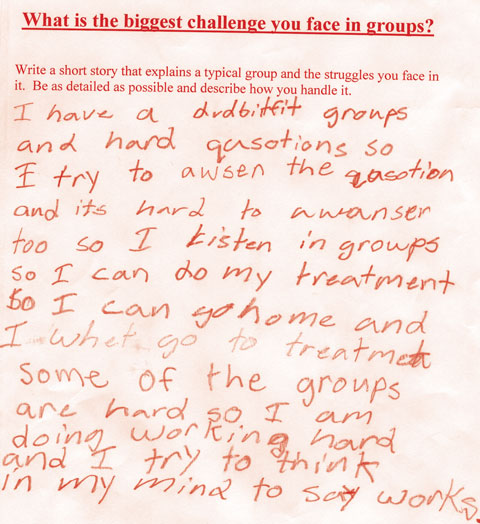

They also lacked skills, and by that I mean they lacked both technical and social skills. Frequently they were functionally illiterate. Many of the kids in the program couldn’t construct a simple written sentence. Their grasp of mathematics was limited. Across the board, they operated several grade levels below what might have been expected for their age. Their abilities to negotiate, listen effectively and communicate productively were incomplete and inadequate.

A writing sample from one of Clem Martini’s theatre and writing classes for youth criminals.

In addition, they frequently experienced exacerbating medical conditions: attention deficit disorder, fetal alcohol syndrome, depression or other psychiatric disorders. They sometimes had a surprisingly long criminal record for their age, and when I say surprisingly I mean I found it surprising. They were genuinely young—between the ages of 12 and 18, with a median age of, say, 15—and they were already in possession of lengthy rap sheets.

Wood’s Homes holds a philosophy that maintains that regardless of the nature of their troubles, young people can be helped and their behaviours altered through programs that address their specific issues. These programs don’t come cheap, however, and consequently they tend to be relatively rare. The Phoenix Program, for instance, which offers treatment for teen sexual offenders, is one of a handful of programs of its kind in Canada. It draws upon clients from across the nation, but can only accommodate 12 or 13 young people at a time. Those young people are in residence for between one and two years. Consequently, the program frequently has a long, long waiting list.

So when the new amendments to the Youth Criminal Justice Act describe an intention to place more emphasis upon denunciation and to provide for automatic “adult provisions” for young people, why do I experience feelings of misgiving?

I have misgivings because if denunciation may be defined as condemnation and criticism, these young people are already extremely familiar with this phenomenon. They have received denunciation at a family level, at school and in the community without any apparent prior deterrent value.

I have misgivings because the young people in question are, by definition, young. That presents ethical questions. Isn’t it society’s responsibility to guide and instruct minors? If an individual isn’t old enough to vote, drink, sign legal documents without guidance or even drive, is it really ethical to turn him over to adult court to receive adult penalties and do adult time?

I have misgivings because I’m not certain that society benefits from incarcerating young people. A report released by the John Howard Society had this to say about transferring youths to adult court to face adult sanctions: “A youth committed to an adult penitentiary will experience a violent and destructive environment… will find no special programs or facilities for young offenders, and limited educational, vocational and psychological resources. He will find a facility where he is exposed to violence, where the murder and suicide rates are high and where there is a high probability of becoming a victim of mental, physical or sexual abuse. He will be taught to settle disputes with violence.” I would go on to suggest that there is nothing like having spent time in prison to transform a young, inexperienced criminal into a more knowledgeable, more dangerous criminal. This is, I suppose, where the rationale for even longer sentences comes in, the thinking being, “If we can’t reform the youthful criminal, we can at least keep them out of our backyards. The longer the better.”

But it should also be pointed out that when it comes to doing “serious jail time” and delivering lengthy sentences, Canadians are already well ahead of the curve. According to an April 1997 report released by the Standing Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs entitled “Renewing Youth Justice,” the rate of youth incarceration in Canada was “twice that of the United States and 10 to 15 times the rate per 1,000 youth population in many European countries, Australia and New Zealand.”

Do we really have twice as much serious youth crime as the United States? Do we truly have nearly 15 times as much as most European countries? And given these statistics, have matters grown to such a degree of urgency that we feel we should be putting even more youths in prison for even longer? Certainly no current statistics support the notion that there has been a substantial increase in youth crime over the past decade.

Furthermore, a report written and released by the Canadian Criminal Justice System noted: “The overcrowding of prisons remains a major concern and challenge in Canada. As a result, the safety of inmates and staff alike is threatened and, ultimately, that of the public…” In listing some of the reasons for this overcrowding, the report went on to explain that “the courts, perhaps influenced by public opinion, continue to rely excessively on incarceration as a reaction to crime…”

A question generally follows this kind of discussion. It goes something like this: “Yes, fine, prisons are awful, not the kind of place where I would want to spend a weekend, but what has any of this got to do with me?”

It’s a good question—good because it’s direct. Good because it comes from a place of self interest, and it’s often from this impulse that people will take genuine action.

A youth committed to an adult penitentiary will experience a violent and destructive environment…will find no special programs or facilities for young offenders, and limited educational, vocational and psychological resources.

And it’s the question that I think many people pose to themselves as they breeze past any number of articles in newspapers detailing the present conditions in prison. (Another riot. Another inquiry. Another desultory non-revelation—the prisons are overcrowded. Another vague promise to address the situation. And so on and so on until the next riot or murder or whatever.) What has any of this got to do with me, sitting in my chair in my living room on the outside?

Well, more than you might think. The walls of prison are surprisingly permeable. What happens within those walls can have serious implications and impact for those who live beyond them. Gangs are very well represented in the prison system. Young inmates often feel compelled to hook up to get a measure of protection, but joining a gang isn’t like joining your local health club. There is no “trial membership.” Young people recruited on the inside become lifetime members on the outside. And that holds major consequences for everyone. In fact, in conversations with prison guards I’ve heard that the explosion of gangs among First Nations populations can be directly traced to earlier determined action to destroy Indian Posse and Red Alert. Convicted gang members were separated and sent to prisons in different locations across the country. But where could they find more willing, more receptive converts than in our prisons—already overpopulated by disaffected young indigenous men? In a short time, new and larger chapters of these same gangs sprang up in fresh locations across the country. We all live with the increasingly complicated and dangerous environment created by these gangs today.

The government maintains that the proposed amendments are part of their commitment to get tough on crime, but the approach is already considered obsolete. An article by the Associated Press from November 2007, reflecting upon previously passed “get tough” legislation in the United States, noted that “…[many] states are rethinking and, in some cases, retooling juvenile sentencing laws. They’re responding to new research on the adolescent brain, and studies that indicate teens sent to adult court end up worse off than those who are not: They get in trouble more often, they do it faster and the offenses are more serious.”

The further irony is that if many of the troubled young people I’ve met were to be polled, they’d probably agree that they should be punished. And why wouldn’t they agree? It’s what they understand best, and pretty much what they’ve come to expect. Their formative years have been punctuated with recurrent, abrupt episodes of brutal and arbitrary punishment. Before he was 10 years old, one young man in program had been stuffed into a sleeping bag, tied in and beaten with a bat by his grandfather. Another individual had been strapped to a wood-burning stove by his father and whipped with a leather belt.

If we genuinely wish to change these young people, we’ll first have to challenge those assumptions they’ve committed to memory about punishment. And to do that, we have to begin truly working with them.

This was clarified for me a few summers back when a group I was preparing for a performance was engaged in an exercise as research for a new script. As part of their homework, the kids had been asked to create a clay model of the kinds of skills they possessed. Several complained bitterly but then proceeded to work. One fellow didn’t, though. Instead, he stared blankly at the clay, then began cursing. When his profanity grew louder, I asked him to move away from the table and let the other guys do their work. He stood up abruptly, knocking over his chair. He swept a handful of the tools from the table, cursed me some more and left for his room. The bedroom door slamming shut behind him seemed to put an end to the outburst, but moments later we heard the startling sound of something breaking. I glanced up and saw him leaning against the sill of the front door, the thick protective glass of the entrance way, shattered. The arm that had punched through the pane hung by his side and was streaming blood.

Regardless of the nature of their troubles, young people can be helped and their behaviours altered.

When a staff member approached him, he seized a long, jagged shard and held it in front of him. The class was quickly terminated, the other participants escorted to the far end of the facility and locked in for their safety. The young man rushed out and loped up a hill, where he stopped, stood his ground and quietly dripped blood onto the lawn. The police and an ambulance were summoned. We called to him, but he didn’t reply.

Since there seemed to be no way of repairing the class or resolving the situation, I packed up the art materials and prepared to leave. As I returned to my car, I heard my name called. I turned and was alarmed to see him racing toward me. I stood, frozen, and asked what he wanted. He told me he wanted to apologize. He said he’d looked at the clay, considered his skills, and realized that he didn’t have any. “I’m empty,” he told me. “There’s nothing there.”

But he came to back to class the next day, arm stitched up, sat down and returned to work.

For the most part, young offenders are damaged. Incarceration won’t fix that. Burdening an already overwhelmed prison system won’t fix that either. But no one ever lost votes by promising to get tough on crime.

So let’s be clear. We can put more young people in prison than we currently do, and we can put them in earlier. We can give them longer sentences. The fact is, though, that our jails are already bursting and no one is interested in spending the millions needed to construct new ones or fix the old ones. All that can possibly occur is that the kids we send to prison today will be released early to make room for the next crop that is inevitably coming round the bend on the very same criminal justice conveyor belt. They will be returned to the streets in good time, and this time they’ll be honed hard from their experience.

Discovery, early intervention, treatment and rehabilitation sound soft, vague and risky and probably won’t get a single politician elected to office—but they may in the end be the only genuine solution. In the meantime, by all means, let’s get on with the denunciation.

Award-winning playwright Clem Martini taught theatre classes to young offenders for two decades. He is an associate professor of drama at the University of Calgary.

____________________________________________