February. Cold Lake is frozen and silent. An ample sky mirrors the terrain below. But landscapes are inhabited even when they’re empty.

I’m here to visit the painter Alex Janvier at his gallery across from the downtown marina. He’s famous. Perhaps even more so than the military base nearby and the fleet of CF-18 fighter jets that occasionally invade the quiet of this place.

It took several months to organize my trip to the “Jewel of the Lakeland” in northeastern Alberta, following up on a chance encounter with Janvier at The Banff Centre, where he was resident in the winter of 2007 as a senior artist.

He greets me warmly, looking solid and healthy for his 73 years. I say as much. “I’ve got a birthday coming up the end of this month,” Janvier smiles. I don’t immediately inquire about the physical setback that changed the look of his work in the late 1990s. Vibrant line paintings in the showcase at the entrance of his gallery, new canvases inspired by a recent journey to Korea, suggest all is better now.

A recent avalanche of accolades and honorifics—two university degrees, a Governor General’s Award, the Order of Canada—is a source of pride, yet Janvier remains humble and perplexed by the attention. “I’m not a learned man,” he says. “I’m an artist. I just paint what I see and feel. I only went to a goddamn residential school.” That’s not entirely true. He graduated from art college in Calgary in 1960.

“Shall I call you Doctor Janvier?” I ask.

“Some people have tried and I haven’t answered yet,” he laughs.

The trajectory of Alex Janvier’s career as one of the founding artists of the so-called Indian Group of Seven has been well traced by media; I, for one, profiled his work exactly 20 years ago in a piece for CBC television. But these impressions of Janvier only skim the surface of his art; much of the power that informs the work is still transparent. His self-appointed task is to draw the attention of the “domineering culture” to hidden aspects of the natural world—the numinous landscape of spirit—which linger along the edges of human hearing, seeing, sensing.

“I’m not a learned man. I’m an artist. I just paint what I see and feel. I only went to a goddamn residential school.”

Of Dene Suline and Saulteaux heritage, Janvier resists being categorized as an “aboriginal” artist. He thinks of himself as an indigenous hunter, attuned to whispers in the land, tracking the shadows, attentive to flashes of insight and tricks of light that point the way forward in all directions. And like the territory he maps with art, there is more to Alex Janvier than meets the eye. His paintings are clues to an extraordinary way of knowing.

Often associated with Norval Morrisseau and Daphne Odjig, among other important artists of the Eastern Woodland School, Janvier differs with the academic account of an Indian art movement, seeing it more as a work in progress. “There really is no Woodland School. Maybe in time,” he muses. But it is still too early. “Native art has been outlawed as pagan stuff, so we weren’t able to express ourselves as the white pagans [did] in Canada,” he chuckles.

“You mean like Lawren Harris?” I respond, referring to the celebrated painter’s “logic of ecstasy” which depicted the Group of Seven artist as a prophet of the land.

Pause.

Janvier explains that he’s more partial to the eye of Wassily Kandinsky, the Russian abstract artist who investigated the imaginal realms as Harris did, especially toward the end of his life.

“Kandinsky [to Russia] was like Morrisseau to Canada,” Janvier says, empathizing with both men’s status as intruders into the formal world of art-making. Kandinsky “was from the cold far east. He wasn’t exactly a shoo-in favourite.”

The work of other seminal abstract painters, such as Paul Klee and Joan Miró, and “all those free-form lines, colour and the whole bit,” impressed him during art school. “I could relate probably closer to Kandinsky, the way he came through the rigour of control—the Russian [Orthodox] church and government control.”

Dene Suline and Saulteaux painter Alex Janvier pauses outside his gallery on the shore of Cold Lake, Alberta.

Kandinsky and Klee were deeply infused with theosophia, translated from the Greek as “knowledge of things divine,” which was bundled with the philosophy of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a mystic revered by many thoughtful artists, writers and thinkers at the turn of the 19th century. Madame Blavatsky was particularly hostile to Darwin’s theory of evolution because it did not go far enough, and failed, in her view, to account for levels of human consciousness. Decades later, another Russian, the philosopher and mathematician Petyr Demianovich Ouspensky, used geometry to account for a hidden fourth dimension of the mind—which, to my way of thinking, concords with the indigenous perception of divinity infused within all earthly things. Janvier agrees with the observation, with an additional insight that “there is a hierarchy of spiritual growth,” which aspires to “the fourth level” and beyond.

“And where are we now?”

“I think this is Level Two,” he chuckles, thinking about the state of human consciousness in the modern world. “That’s why I’m here, [why] I’m painting.” To which he adds, “I must have botched out of two and had to come back and fix that.” He lets that one hang. And I sense he has a surprise in store—or maybe not—if I’m patient.

Our ellipses of conversation remind me of Tibetan teachers I’ve met in southern Alberta who speak in a similar roundabout way. But I implicitly understand his drift. And to look at Alex Janvier—his distinctive earlobes—I risk offence when I mention they are similar in shape and sized in the fashion of Buddhist deities portrayed in thangka wall-hangings and statues. He smiles. “In China,” where he participated in a major cultural exchange, “I was venerated in 1985. People actually felt my ears. In Korea, the same thing. The first thing they noted was my big ears.”

Of his first art teacher: “He got me to see beyond being an Indian, beyond the reservation—beyond Canada.”

He does look like a lama.

While 20th century masters of abstract art are Alex Janvier’s primary influences, he has greater affection for his first teacher, Karl Altenberg, a professor of art at the University of Alberta, who spotted the lad’s talent and took him into the protective custody of summer school.

“He got me to see beyond being an Indian, beyond the reservation, beyond Canada,” Janvier fondly recalls of those summers in Edmonton, four altogether, away from the Blue Quills residential school. “There was a world out there that I could associate with, without being bogged down by any [Indian] agent or priest or whatever. For the first time, in my mind I was liberated.”

Janvier’s artistic emancipation was complete during his third year of training at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology & Art (as it was known before it split into SAIT and the Alberta College of Art + Design). He came upon his technique of “delicate line” in 1959, which today is acknowledged as “a new visual language,” according to art historian Ann Davis at the Nickle Arts Museum.

Drawing upon a web of colourful lines to connect indigenous traditional knowledge with the semiotics of a world marked by machine technology, Janvier credits two other teachers, Frank Palmer and, in particular, Marion Nicoll for encouraging his innovative signature style. “She wasn’t interested in the art establishment,” the aesthetic practices of the British Academy, which inculcated a majority of her fellow instructors on “how to paint the land.” Their formal conventions of the way things ought to be on canvas, he grumbles, “had nothing to do with this place.”

Alberta could have lost one of its finest painters to hockey. Janvier played house league defence and left wing in residential school, and later made the tech team at art college. “I could have played four years, but I got hurt in the last year,” he says. He didn’t complete the season.

“All in all, I scored one goal,” the artist grins, and like a veteran in a Legion hall he recalls the defining moment of his sporting career. “I hit the ice ahead of the puck, and kind of skinned it. So the puck went in slow and the flash of the [goaltender’s] stick went out. And I guess the damned thing just snuck in on ice level. That was very unprofessional, but it was the greatest goal I ever made!”

His gentle humour and soft-spoken manner are betrayed by the reservoir of strength reflected in the fine art that inhabits every available space in the refurbished bank building that houses the Janvier Gallery.

The irony that this extraordinary body of work hangs in a former financial institution is not lost on the painter. The art, now valued in the millions, was nearly worthless in the eyes of fiduciary officials, whose doors he once knocked on for support decades ago. “That attitude still prevails,” Janvier says, speaking to the truth of being native in polite white culture. “You try to go to the bank and they’ll tell you in a small voice: We are sorry we can’t extend our services to you.”

“You’re still getting that treatment today?”

“Of course, except in this room here. This is a bank,” he pauses for effect. “But there’s no money in it.”

Another shared laugh.

“Have you had lunch?” Jacqueline Janvier interrupts before I ask my next question. The love of the artist’s life since 1968, Jacqueline runs the business of the gallery and her authority is never in question. “We met in church,” she says, remarking how her future husband locked eyes with her. “You stared,” she says playfully. “I was listening to the choir,” he protests, noting how sacred music affects his life. In my 1989 CBC profile, for instance, Gregorian chant looped in the background while he painted in his studio. He later soured on organized religion.

“Did you leave the church or did it leave you?”

“We parted in good faith,” he responds dryly.

“Under the Creator’s eye, natives have remanifested. And no church or government can do a damn thing.”

Roman Catholicism is inching its way back onto Janvier’s hit parade. While the hurt of the residential school at Blue Quills still lingers, he recently softened his resolve to steer clear of any priest on a mission with a visit to the Franciscan retreat in Cochrane.

I have other questions, but they must wait because Jacqueline shoots her husband that “look after the guest” look. “You guys can talk all day,” she says, ordering us out of the gallery and over to the diner on the waterfront.

We walk the half-block or so to the restaurant in Clarks General Store, a heritage building with a sense of local history that nonetheless overlooks the contributions of indigenous people. The service is friendly, and the artist is no stranger here. But I can’t help but notice the absence of his work—not even a postcard—in the popular diner.

“I don’t believe there’s a Canadian history,” Janvier says, stirring his teacup. He points to the Majorville medicine wheel in southern Alberta and other stone monuments on the prairie—some said to be older than Stonehenge—as survivors of an ill-founded movement to obliterate indigenous claims to the land. He explains his current position that the “domineering culture” has made a mess of the territory, which it “rents from natives,” and that it’s time “Indians become the landlords again.”

The waitress replenishes Alex’s teapot before moving along to the next table. A fighter jet blasts by. “To save us from the Russians,” quips Janvier before excusing himself.

Alone, I look the diner over. There’s a retro feel to the place; the attractive ceiling, I’m told, is embossed tin-plate original to 1922. I enjoy the moment until an old disco hit squirts out of the sound system. No one else seems bothered by the clash of aesthetics.

Though none of his work is displayed in the local diner, Alex Janvier is well represented elsewhere. His work adorns public places such as hospitals, government buildings and prominent museums in Alberta’s cities, while a casino on the nearby Cold Lake First Nation sports a large triptych over a bank of slot machines, complemented by wall-to-wall carpeting, its design drawn from a detail from one of Janvier’s most colourful works. Even outdoor billboards celebrate his ability. I first caught sight of one of his spectacular murals in the 1970s, a signature piece that unites the four glass pyramids which constitute the Muttart Conservatory in Edmonton’s river valley.

Much has been written about Morning Star, his 1993 masterpiece that covers the inside of a huge cupola perched seven storeys high in Canada’s Museum of Civilization; the curvilinear building, superbly sited on the land, is the inspired creation of another prominent Alberta-born native artist, the architect Douglas Cardinal. What is less well known is how Janvier’s 4,500-square-foot mural fulfills a commitment he made with Norval Morrisseau to remake the nation’s cultural icons into a symbol of indigenous power.

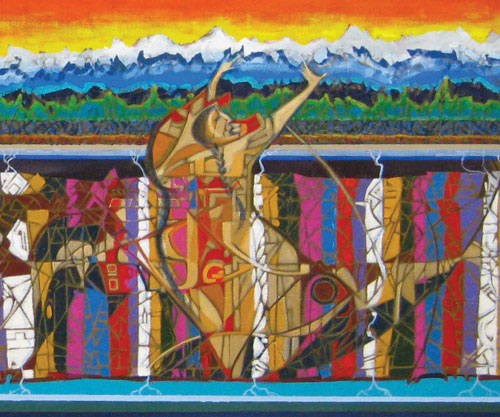

A detail of Sky Talk. (Don Hill)

Morrisseau’s stunning solo retrospective in the National Gallery in 2006 “ended a long history of apartheid at the country’s leading art institution,” the Ottawa Citizen rightfully recorded, noting that in the gallery’s entire 126-year history not one native artist had been accorded a similar honour.

It was the explicit purpose of Morrisseau, Janvier, Daphne Odjig and the rest of the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation of 1973 to muster past the patronizing tone of the art officials, which continuously dogged the Indian Group of Seven, a name coined by the press in Winnipeg.

“We found ourselves caught in a no-man’s land in the art world.” Janvier winces with the memory. “We were poked fun at—politely.”

It was decided at the inception of the group in Manitoba, which later expanded to include Bill Reid on the west coast, that their prime directive was to reframe the views of the art mandarins. “Norval and Bill went east-west, and me and Joe Sanchez took the north-south line.” Janvier’s Morning Star dome in the Museum of Civilization bears a distinctive cross that demarcates the lay of the four sacred directions, which signifies the beginning of how “we took back this land.”

Took back the land…?

“Under the Creator’s eye, we [have] remanifested,” he says, speaking of native fine art as the means of consecrating cultural icons and places deemed important to Canada. “And there’s no church or government that can do a damn thing about it.”

Thinking back on the historic National Gallery opening, he describes Morrisseau propped up in his wheelchair “mobbed by the collectors” and a fawning crowd, and how Copper Thunderbird (as he is known to his Anishinabe kin) seemed genuinely touched to see his old colleagues Joe Sanchez and Janvier. Copper Thunderbird could only offer tears to acknowledge the realization of their long-shared dream; Parkinson’s disease had robbed the shaman artist of speech and the ability to paint.

“I saw the tumbling,” says Janvier quietly of the event. “It was the Berlin Wall coming down on the National Gallery. We just kicked ass.”

After lunch, we step outside to snap a few photographs. The air is crisp and clean. Cold Lake’s blanket of ice is illuminated here and there by ripples of horizontal light that line the ambient cloud cover. It could be pregnant with snow—the sky tells of it—but I would know for certain if I lived here full time as Janvier has since the early 1970s.

Despite a cautionary warning, I somehow manage to step backward while taking a photo of Janvier close to the shore. Cold Lake is true to its name, and as my boot fills with slush, I call upon something appropriately profane. It remains a sacred lake, nevertheless.

“The lake doesn’t belong to us,” Janvier says, “but to tribes from all over.” He tells of local people finding a big black chunk of obsidian from Yellowstone, prized for making extremely sharp tools to cut up fish. They’ve even found arrowheads from as far as South Dakota.

“There’s energy in this landscape,” continues Janvier, looking out over the ice and beyond. “Especially if you go in the middle of the lake. There’s an awesome feeling when you’re right in the middle. It’s so powerful.”

We head back to the gallery. It’s getting dark. There’s more snow in the forecast and Edmonton is at least four hours away in this weather. Jacqueline tells me to stay the night and “visit with Alec in the studio.” It is a friendly invitation, and to disobey would not be smart.

I follow the tail lights of his SUV to Cold Lake First Nation. We go slow at first, picking up speed after the pavement ends. Pulling up to his studio, an elegant log construction set beside his first home, now occupied by one of his children, Janvier declares: “I built these two places with my own hands and my own money.”

If every piece of art has a story to tell, what greets me inside Janvier’s studio makes me feel alert to the power of this place. I am immediately impressed by a large, circular shield infused with flowering pinks and greens, with shifts of yellow, blue and brown.

“I don’t normally show this to everyone,” he says, directing my attention toward a protective wrap of industrial-strength plastic that stretches from one end of the studio to the other. He scrambles up a ladder, and pulls up the curtain.

I gasp.

“This is 1491,” he says of his newest mural, which he began painting two years ago. Although it’s finished, he’s not ready to part with it. He wants to let the piece dry some more. Sit with it. “These are the laws of the land. These are layers and layers of the rules set into the ground.”

And you can clearly see what he’s talking about.

“The water table is there and will seep its way up. Then you have the iconic Rocky Mountain range, which is the second phase of the world that we live in. Prior to that was phase one—probably the Laurentian times. The natives are talking about the third. There’s going to be another something or another happening. My dad said if you don’t see it, and your children don’t see it, your grandchildren would see it for sure because it was that close. In the end, he said, people are just going to go crazy. They’re going to go crazy over money—over everything.”

“What do you call the mural?”

He is uncertain. “Some say it represents Mother Earth,” a reference to the woman with outstretched hands embracing the sky. (When I call him later he refers to it as Sky Talk, which he preferred from the start. And later still, when I get Jacqueline on the phone, she says, “You mean the 16-footer.”)

Every line in this new piece shows a steady hand. In the late 1990s, Bell’s palsy severely disrupte d Janvier’s ability to paint in his signature style. His right side was affected. During his winter residency at The Banff Centre in 2007, on the side of Tunnel Mountain (traditionally known as Sleeping Buffalo), he awoke one day to the delight of a morning sun lighting up the whole of the mountain.

“It displayed all the rich, warm colours of the spectrum. I happened to be waking up, sitting at my breakfast, looking at this mountain. And bang, there’s all the colours. It was quite explicit, quite clear.” Soon after, he inexplicably defied the expectations of modern medicine and regained his ability to paint in his traditional way.

Sleeping Buffalo is a place of power for the Blackfoot. “Well, it certainly gave me back my ability to do those flowing lines again,” he says. “That is transference of unseen power. You can’t see those powers until it happens to you—when you need it.”

Sleeping Buffalo is also a dreaming mountain. The people of the Blackfoot Confederacy use it to receive “the natural laws of the land—of the earth, the sky and of the spirit. I’m not scared to talk about these things,” he says. “I’m scared you are going to write some willy-dilly stuff.”

On the inside door of his studio, Janvier has written “To all my friends who enter through this door. Ho’an ekolanthe. There is peace here with your arrival.” To the right of the invocation is a photograph of his first teacher, Karl Altenberg, smiling bravely in his hospital bed only weeks away from death. To the left of that image is the number 5 marked on the door, and slightly above and off to the left is a newspaper clipping trimmed with green at the top and bottom, the obituary of Norval Morrisseau.

“Do you miss him?”

“Ahh—I got him on my doorway. He’s right there.”

I snap off several more photographs as Janvier gestures near the entrance to his studio. Looking over my pictures, much later, I spot a peculiar ball of light hovering to the right of Norval Morrisseau’s and Karl Altenberg’s spots on the wall. And inside it I see what looks to my eye as the likeness of a human face. Light can fool with your mind. But why only in this one picture?

I’m enough of a pro to know that it could have been a lens flare, a dust mite caught in the flash, but I’d like to think Norval Morrisseau was in the room with us that day. It felt right—the sense of an elder watching in on us. And it’s not a bad way to live.

As I type this text into my computer, it is the wee hours between night and dawn. It seems right to reflect on the supernatural art I have encountered.

Alex Janvier’s studio is never empty.

Don Hill is a “thought leader” in The Banff Centre’s Leadership Development Program. He lives in Edmonton.

____________________________________________