Guy Smith, the president of the province’s biggest union, the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees, is grey haired but spry. He chooses his words politely but with candour. Over the course of two long interviews, one at a Starbucks tucked away in west Edmonton between 170th Street and 172nd Street, and the other at AUPE’s impressive modern headquarters 12 blocks away, he had no vindictive words for any of the seven premiers that have governed the province since 2009, the year he was elected to the AUPE’s top job. Those premiers are, in order, Ed Stelmach, Alison Redford, Dave Hancock (interim), Jim Prentice, Rachel Notley, Jason Kenney and now Danielle Smith.

Danielle Smith’s party has a certain record in its dealings with workers. During the United Conservative Party’s first term in government, Alberta’s minimum wage for teenagers was cut from $15 to $13. The minimum wage for adults remained at $15, even in the inflationary years that followed the COVID-19 pandemic. Compensation benefits for injured workers were cut by half a billion dollars over five years. The UCP changed the rules on overtime to give employers extra leverage over workers and decrease the need to pay out time and a half. The then-finance minister, Travis Toews, asked members of the United Nurses of Alberta to accept 3 per cent salary rollbacks in July 2021. Similar wage rollbacks were proposed for homecare aides, licensed practical nurses and other members of the AUPE.

“2024 is payback time,” says Guy Smith with a smile. Approximately 82,000 of the AUPE’s 95,000 members will need their job contracts renegotiated in 2024—that’s 65 per cent of the total membership—and Smith is bullish on the union’s prospects. “They [the workers] were on the front lines, struggling with short-staffing issues, mental health issues, inflationary issues. I wouldn’t want to hazard a guess as to what our demands will actually be, but they’ll probably be significant.”

Whether the new premier will be any friendlier to organized labour than the previous one is an open question, but Guy Smith vs. Premier Smith will be one of the major narratives of the UCP’s second term.

The AUPE’s members are involved in a wide range of services that are vital to Alberta life. They’re responsible for government administration and policy design and implementation; some are firefighters; some are museum staff, correctional workers or social workers. The interpretive guide at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is an AUPE member.

The pandemic may have subsided, but the struggles of the post–pandemic era are no less challenging for AUPE’s members. These challenges are in three main categories: the increasing cost of living, the privatization of work places, and the condition of perpetually “working short,” with insufficient staff to manage workloads.

Consider the day-to-day reality faced by Samantha Samborski, employed as an individual support worker at a residential homecare facility in Edmonton. She cares for children with severe disabilities who depend on her and her co-workers for almost all of their basic needs. As she explains it, children come to the facility “because of car accidents, or some have just had other accidents happen to them in the early stages of life. And we’ve also had children that have tried to commit suicide. So we see a wide variety of the emotional side of humanity.”

The job has become a lot harder in recent years. “The benefits and pay have not kept up with the realities of today’s world and the inflation crisis,” says Samborski. “More and more workers take second jobs or rely on overtime to make ends meet. And since the pandemic, it’s only highlighted the lack of respect that so many of us feel. We are expected to do more with less.”

Many of Alberta’s public workers feel disrespected: “We’re being expected to do more with less.”

In addition to her work duties Samborski is the chair of AUPE Local 009, which has roughly 600 members. When she started with the local eight years ago, it had over a thousand members. The decline is mostly due to privatization. Facilities close down and reopen as non-profits or private agencies, or they close down permanently. This impacts unionized staff, who often have to go work in the non-profit or private sector, often for less money. Samborski says the facility she works at in Edmonton is at risk of one day closing because it has been ordered to not take in any new patients except under exceptional circumstances. In the summer of 2020, staff were told by email that the government had “alternative service delivery models” for this home and similar residential facilities in the province. As of August 2023, the home was still open and in public ownership.

Samborski is one of the 82,000 AUPE members whose contract is up for renegotiation in 2024. The legal context for collective bargaining has changed in recent years, in part because of the essential services legislation the NDP government brought in to keep the province compliant with a Supreme Court decision. This legislation requires locals such as Samborski’s to have an essential services agreement in place to determine what services will be offered in the event of a strike. No strike action can be taken without such an agreement.

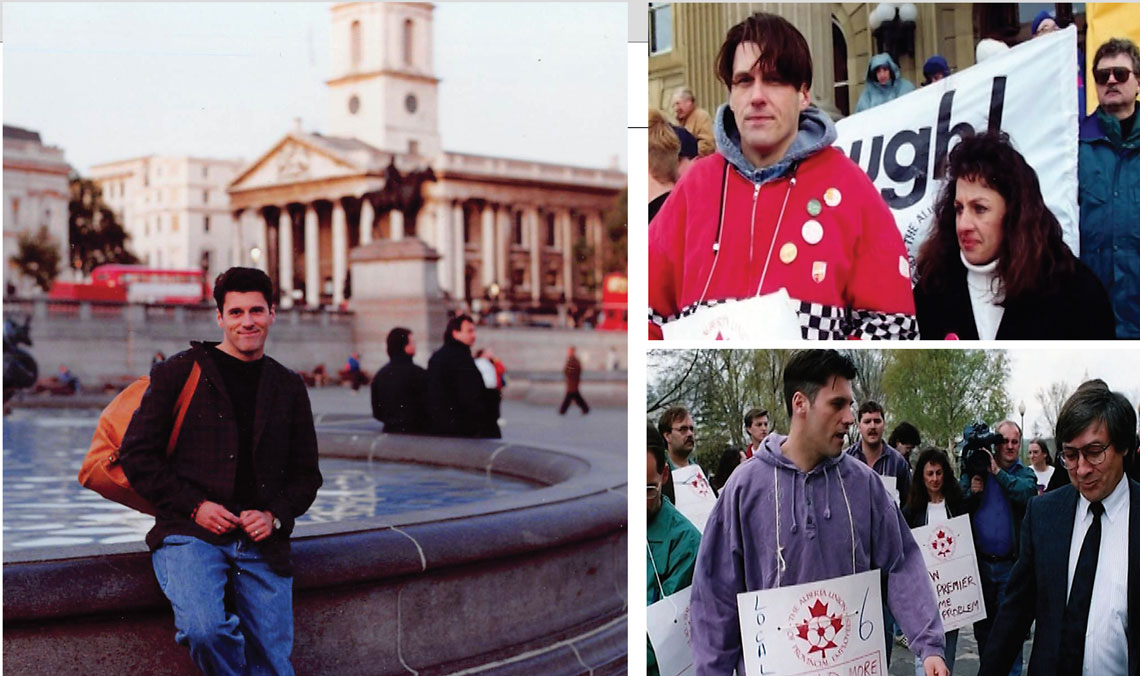

LEFT: Smith in London’s Trafalgar Square, circa 1987, after a rally opposing apartheid. TOP: Smith at a protest against Klein-era cuts, circa 1994, with mentor Linda Karpowich, former AUPE local 006 chair and Alberta Federation of Labour president. BOTTOM: Protesting cuts at Yellowhead Youth Centre, circa 1992; at right is then-social services minister Mike Cardinal.

Aside from the legal considerations, the AUPE is up against an old ideological nemesis: the UCP has given no sign of abandoning its preference for private over public delivery of services. The mandate letter of July 18, 2023, to incoming Health Minister Adriana LaGrange, for example, called for “supporting primary care as the foundation of our healthcare system by assessing alternative models of care and leveraging all healthcare professionals.” While vague, “alternative models” can easily be interpreted as quietly encouraging more privatization.

It’s a trend Guy Smith has seen before, in particular during the premiership of Ralph Klein. “We saw the privatization of entire departments. Transportation, road-clearing and all the infrastructure for government registries,” he says. In the early to mid-1990s, the AUPE’s membership declined from 50,000 to 34,000. The union teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. Former president Carol Anne Dean, elected in 1993, recounted her memory of those years for the AUPE’s 40th anniversary magazine. “It was like bombs were going off everywhere, every day, all the time,” she said.

Smith has participated for long enough in the AUPE, right back to his time with Local 006, that he has an intuitive feeling for the ebb and flow of the Alberta labour movement’s fortunes and how each moment requires its own strategy. When he was a care worker at the Yellowhead Youth Centre in Edmonton, he participated in a 1990 strike that the AUPE had neither sanctioned nor sought to prevent. Media coverage of the strike was extensive, and at least one video from CFRN News is still available online for those wanting to view it. Six managers tried to do the job of 100 striking workers. It did not go well. Anywhere from 16 to 40 youth ran away, and the police had to make multiple arrests. “All hell’s broken loose,” a resident told CFRN News during the strike. Smith and his fellow union members tried to encourage orderliness among the youth, but the relationship between troubled teens and their temporary caregivers, the managers, was so fractious as to be unworkable.

It was a defining moment in Smith’s career. “I built that worksite from an inactive worksite into one that led a strike, and it was thanks to these trusting, supportive relationships as workers,” he remembers. “We were sticking up and standing next to each other when we needed to.… It taught me a lot about other people’s resilience.”

Smith is the son of a barrister and a feminist. His mother, Mair Smith, helped create the Alberta Status of Women Action Committee, of which Helena Freeland, mother of the current deputy minister of Canada, was also a member. From his mother, Smith learned to fight for his beliefs. From his father, he learned different lessons. “I always respected my dad’s judiciousness. Yet the way he treated people was very kind, gentle and fair.”

LEFT: Smith has performed labour songs at many rallies; here, he’s at a 1999 protest to oppose Premier Klein’s plans to privatize healthcare. RIGHT: Addressing AUPE’s annual convention in 2022. Smith: “Society needs to be built on co-operation and collaboration–yet the friction within the various parts of society has to continue. That’s how society move forward.”

The way Smith approaches his job has also been shaped by geography and culture. His wife, Sherry, is from a family of settlers, her parents and grandparents having come to Alberta from Ukraine and Denmark. Smith met Sherry in Grande Prairie and their roots in the town run deep. “I do have a very deep fondness for the kind of community you find in a smaller town,” says Smith.

As anyone who has listened to Smith speaking for more than a few seconds will know, his own family roots are quite different. He was born in St. Chad’s Hospital in the central England city of Birmingham. From there his family moved to Sidcup in Kent before making the big decision to emigrate to Canada. Smith first landed with his parents and sister in Edmonton in 1973. “Then we took the Greyhound bus from Edmonton to Grande Prairie. Six hours! And I thought, ‘Where are we going?’ Because when you go on a six-hour coach ride in the UK, you go through hundreds of villages and towns and cities. So what took me was the vastness, the space.”

He remembers Grande Prairie as a very welcoming community. His parents became well integrated into the community, his father working as a provincial court judge, while both of them also maintained active hobbies—Smith’s mother loving crafts and pottery, his father involved in amateur theatre. In England Smith had been among the last to be picked for the soccer team and had to stay out of the way in the back, chiefly to avoid mistakes. In Canada he was given more exposure to the game and became a better player, which he describes as very positive for his confidence. In 1977 his parents divorced, and Smith moved with his mother and sister to Edmonton. He would have been 15—for many people, the years of teenage rebellion, but he provides no indication of responding with angst or anger to the divorce or to being uprooted again.

His education and career followed a smooth path. After high school, he attended the University of Alberta, earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology and got a job at the Yellowhead Youth Centre in 1983. “I didn’t think much about anything except earning a paycheque and having fun and playing music… and really enjoying my job as a youth worker.” Sherry was at that time a schoolteacher.

They both quit their jobs to go live in England for a while. It’s clear there was a wanderlust, especially in Sherry, that had to be satiated, even if it meant living with very little money. It is this chapter of Smith’s life that appears to have galvanized his worker sympathies. In London he became involved in the Militant Tendency, one of the most radical factions of the 1980s Labour Party. He went doorknocking for a Militant candidate in Tower Hamlets, an old working-class neighbourhood of London’s East End, where socialist ideas were not at all new. There was a strong tradition of union militancy in the area.

Some 82,000 AUPE members will need to renegotiate their job contracts in 2024.

“I was intrigued by their outlook of building a socialist society run by workers, redistribution of wealth and common ownership of the means of production, and all that,” he says.

The Militant Tendency suffered a very public defeat as Labour purged its ranks of the faction’s most outspoken and active members. A critical turning point came in 1985—and it serves as an interesting test case for how Smith views his leadership responsibilities in balance with his idealism and radicalism. Militant was at that time in control of Liverpool’s city council and in a prolonged fight with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, which had imposed austerity measures. Under Militant, Liverpool ran an illegal deficit budget to continue spending on social programs. But as money ran out, city councillors hired taxis to go around handing out redundancy notices to city staff, convinced that overseas loans could eventually be secured to hire them back.

The then-Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, mocked this “grotesque chaos” in a speech delivered to hundreds of attendees of the party conference at Bournemouth, and the purge of Militant proceeded in ruthless style.

“I think the Liverpool experience actually shows that when there are worker collectives run very much from a grassroots perspective, established institutions are threatened,” Smith says. “However, I do recognize and understand the need for consistent governance, for consistent decisions as much as possible, and for risk mitigation, transparency and accountability… AUPE members need stability in the organization that supports them. Sometimes I’ve had to dial back on my principles for the greater good, and sometimes I’ve had to push those principles for the greater good as well.”

Guy Smith believes that when unions win concessions for workers, all Albertans benefit.

Smith likes the analogy of a chess game for how labour strategy can play out. In the upcoming contract negotiations for 82,000 of the AUPE’s members, Premier Smith will be the chief opponent. “Society needs to be built on co-operation and collaboration, yet, to a degree, the friction within the various parts of society has to continue—that’s how society moves forward,” he says.

He doesn’t believe that Alberta’s NDP, typically seen as an ally of organized labour, has always played the chess game particularly well. Considering Rachel Notley’s four years as premier, Smith says he saw some clear errors of judgment, using as an example the passing of Bill 6, the Enhanced Protection for Farm and Ranch Workers Act. “I think there was some naïveté there,” says Smith. He interprets the fierce resistance to the legislation as a sign that the NDP had misread the mood of rural Alberta.

“What happened over time is that they [the NDP] started getting very insular,” he says. “I didn’t have my first real face-to-face meeting with Premier Notley, even though I’d been asking for one, until three years into her mandate.” He thinks the NDP’s subsequent time as the Official Opposition (2019–) has strengthened the party, and that it’s now time for the NDP to give Albertans something to fight for, not merely against. That’s what the AUPE plans on doing,

While the re-election of a staunchly conservative government last spring might seem to indicate a return to traditional Alberta politics, Smith makes no assumptions about how the next few years will play out. “I think we know the premier has certain beliefs and a direction, but it depends on how the government operates. A good number of new MLAs have come in with new ideas and new backgrounds.”

The cost-of-living crisis has raised the stakes considerably. Mary Jane Fisher has been a licensed practical nurse for over 12 years, usually employed by Alberta Health Services. She is the chair of AUPE Local 045, lives in Okotoks and has a job at a homecare facility in High River. She and her husband renegotiated their mortgage in early 2023, and their monthly payments jumped by $900. “I’m one of the lucky ones,” she says. “My kids are grown up. They’ve left the house. If my kids were still little, in school, $900 a month would have absolutely broken us to the point where we would lose our home. So much for savings, retirement income—anything like that’s completely gone out the window. We’re just barely scraping by.”

Fisher is not alone in her struggles. She says morale among her fellow healthcare workers is low. The repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic are still felt acutely. “You feel like you’re a healthcare hero, and then you go to feeling like you’re a zero when you’re not getting the recognition and the respect that you deserve.”

Like many other leaders in the AUPE, Fisher is deeply concerned about privatization. She describes a new practice called “client-directed homecare.” Under this model, if a client qualifies for homecare but the local facility cannot meet the needs (typically because of staff shortages), the government provides funds through Alberta Blue Cross for the client to hire their own private caregivers. According to Fisher, under such arrangements, the wages paid to the caregivers—those actually providing the frontline services—can sometimes be as low as the minimum wage.

Private homecare is already widespread in Edmonton and Calgary. Now, Fisher says, the risk of privatization is coming to rural Alberta. “In rural Alberta,” she explains, “we’re still lucky that we have in-house healthcare aides. That provides way better streamlined services, because nurses and healthcare aides are all in one office. So our healthcare aides know our nurses, they know exactly what they need to be doing with their clients, and it’s way better.”

Guy Smith believes unions can continue to make progress and win concessions for workers in Alberta, and by extension create benefits for all Albertans. He’s seen evidence of it during his entire career and in all parts of the province, including rural Alberta. He’s seen enthusiastic support for workers on picket lines. “Big trucks—people who may work in the resource sector—they’re honking and waving and dropping off coffee because they actually understand

that sort of David-and-Goliath kind of struggle,” he says.

If the past tells us anything, Smith says, it’s to never count out the AUPE. From near-bankruptcy and rapidly declining membership in 1995 to full coffers and 95,000 members as of 2023, President Smith says he’s ready to take on Premier Smith. “At the end of the day, we have ourselves to rely on, and that’s it,” he says. He’s not smiling.

Laurence Miall is the author of Blind Spot (NeWest Press) and writes on politics and culture for various publications.

____________________________________________