Our society helps individuals and families in need through income support, part of a larger system of social assistance. The program was in the past sometimes referred to as “welfare.” “Welfare” took on a pejorative meaning that didn’t do justice to the program’s purpose or approach: that the whole of society should provide assistance to those in greatest need.

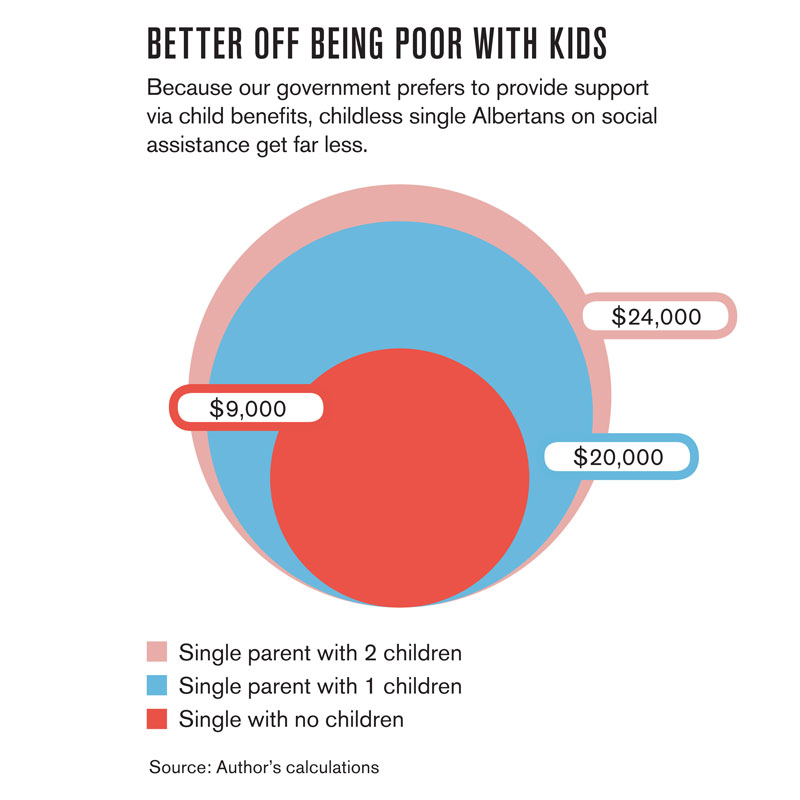

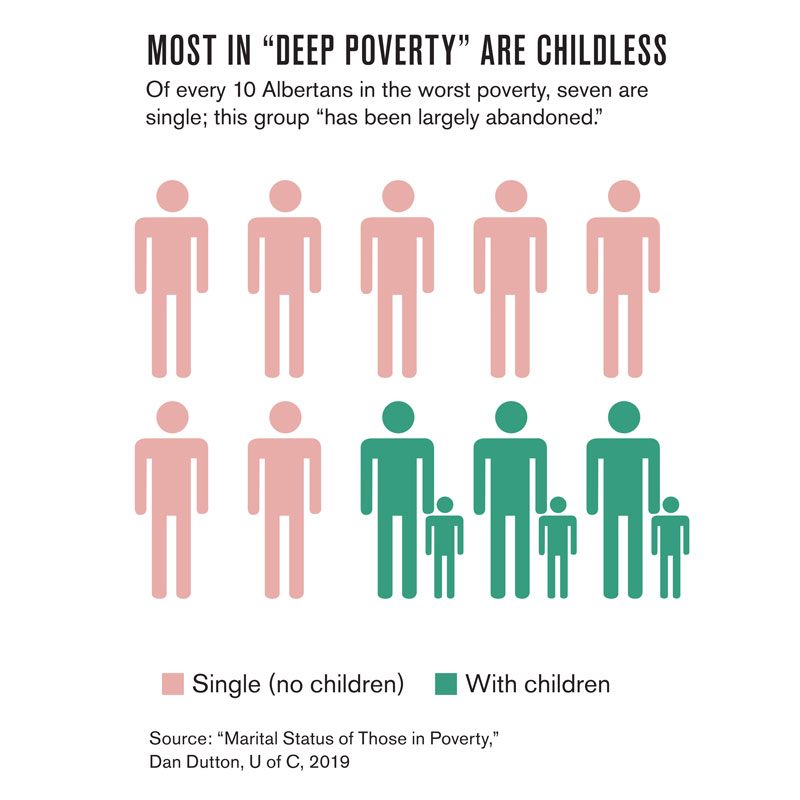

How best to support people in need is a vexing problem of public policy. Federal and provincial increases to child benefits have lifted many families above the poverty line and reduced pressure on social assistance. The majority of people dealing with deep poverty, however, and nearly three-quarters of those who receive income support, are single. Recent policy changes provide no benefit at all to these people.

Income support is only a small part of what is sometimes referred to as the “social safety net,” designed to catch people falling due to economic challenges or ill health or because they are victims of abuse or violence. The net consists of government programs, faith-based and other private charities (e.g., food banks, domestic violence shelters, immigration services, homeless shelters and children’s services), and family and friends. Wholly publicly funded components include medicare, employment insurance, the Canada and Quebec pension plans, old age security and workers compensation. Some aspects of the social safety net are in the form of regulations such as minimum wage laws and, in some jurisdictions, rent control.

The social safety net exists because as a society we believe we should help our fellow citizens. Philosophers have approached the question of what that help should look like by asking people to describe the society they’d prefer to be born into assuming they didn’t know their personal circumstances—whether they’d be born into a wealthy or a poor family, born in good health or ill, or what circumstances might later befall them. People tend to answer they’d prefer to be born into a community that supports the poor and the sick.

One of the most important parts of the social safety net provided by government is income support. The federal government and each province and territory provide such help, though in different ways.

Locally the provincial government has two programs for this purpose: Alberta Works (AW) and Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH). These programs are similar in size but serve different clients. AW offers income support to individuals and families who don’t have the resources to meet basic needs; AISH provides income and health benefits to Albertans with a permanent medical condition that prevents them from maintaining employment. In January 2019 AW maintained 59,940 cases, while AISH had 62,247.

To be eligible for either program, a recipient is restricted in the amount of wealth they can own. With AW, for example, a lone parent with one child is typically limited to about $5,000 in liquid assets beyond the value of certain basics such as a home, an inexpensive vehicle and up to $5,000 in RRSP savings. These are exempt to ensure that recipients who are eligible for ongoing benefits are not forced into total poverty, which would make it harder for them to eventually reduce their dependency on social assistance. Clients of AISH have a higher asset limit ($100,000) in recognition of their restricted ability to earn income. The value of a home, a vehicle and certain other assets are also exempt.

AW clients can earn a limited income without penalty. For example, a lone parent may earn up to $230 per month without losing benefits. Beyond that, their benefits are reduced by 75 cents for every dollar earned. Initially there’s an incentive to find employment while receiving income support, but a minimum-wage earner might see very little benefit in working more than 15 hours per month. The ideal system balances directing resources to those in greatest need while encouraging them to find employment. Determining the design of that ideal system is challenging.

An oddity of income support, not only in Alberta but in other provinces, is that benefits have generally not been indexed for inflation. Instead, they have been periodically increased, usually after their value has been seriously eroded by inflation. It is especially strange because Canadian governments have been careful to protect seniors from inflation by indexing CPP and Old Age Security benefits, and have protected income earners by indexing the tax system since the early 1970s. Why the most vulnerable Canadians shouldn’t receive this same benefit of indexation is a serious failure of public policy. In Alberta, income support clients (both AW and AISH) finally saw their benefits indexed for inflation this past January.

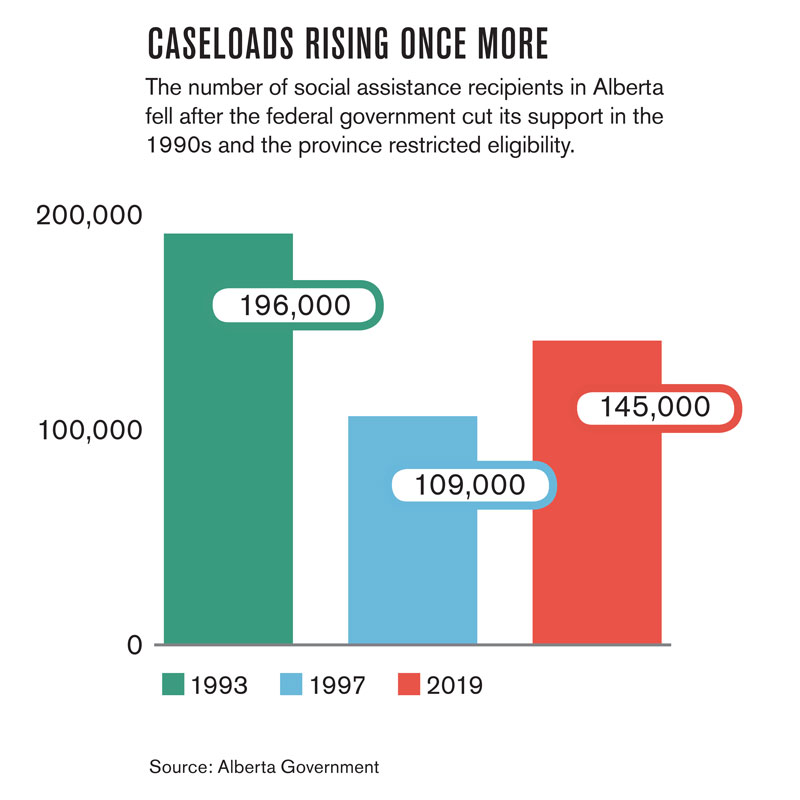

Support for the neediest Albertans has evolved greatly over the past 25 years. Beginning in the 1990s, the federal government stopped paying 50 per cent of the cost of social programs designed and implemented by provincial governments. This meant the provinces could no longer spend “50-cent dollars” on social assistance, causing them to rethink the design of their programs. Their budgets were also under pressure from rapidly rising healthcare costs. The provinces introduced measures that made their programs harder to access. As a result, the number of people receiving social assistance fell, sometimes quite dramatically, in all provinces.

In Alberta, for example, the number of people dependent on social assistance fell from 196,000 in 1993 to 109,000 by 1997 following provincial budget cuts. Today AW and AISH together support approximately 145,000 adults and children.

In the past two decades the federal government has found itself in a position to increase its role in funding social assistance. Its contribution, however, is very targeted and restrictive. Each of these features has important implications for people in need of income support.

The federal government’s contribution to social assistance is almost wholly by way of children’s benefits. Providing support this way has proven attractive to Conservative and Liberal governments alike over the past 20 years. Whereas two decades ago 15 per cent of total social assistance benefits (provincial and federal combined) provided to an Alberta couple with two children was in the form of child benefits, today it is over 43 per cent. Alberta recently hopped on the bandwagon of providing income assistance via child benefits with the Notley government introducing an Alberta Child Benefit in 2016. (The ACB is about one-seventh the size of the federal child benefit.)

The federal government delivers its support by way of the tax system. Twenty years ago 80 per cent of the total income support provided to an Alberta couple with two children came in the form of a monthly cheque received after proving need to a provincial caseworker. Today that has fallen to 50 per cent. Half of the income support provided to this family now comes in the form of benefits that are obtained only by completing tax forms. These include federal and provincial child benefits, the GST rebate, carbon tax rebates (until recently), and additional, smaller benefits. Obtaining these requires the ability to accurately complete increasingly complex tax forms. Growing evidence shows that a significant number of needy people are failing to do so.

What’s more, relying on the tax system to deliver benefits subjects claims to challenge by the Canada Revenue Agency. This is proving increasingly difficult for families seeking support for children with disabilities. Applications for certain benefits are less often determined by the considerations of a caseworker following an interview with applicants and a review of medical files and more often by the impersonal judgments of the Canada Revenue Agency.

Finally, many of these benefits, such as the GST credit, the Alberta Child Benefit and the carbon tax rebate, are paid quarterly, meaning that families must bridge those payments over the intervening three months. For families living hand-to-mouth, this can be challenging.

The ever-growing emphasis on providing income support via child benefits is most problematic, however, because the person in need is more often than not someone without young children. Researcher Dan Dutton, in a study released by the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy in 2019, shows that nearly 7 out of every 10 Albertans experiencing deep poverty are single. These people don’t get child benefits, of course, and so receive considerably less income support. A single Albertan receiving social assistance must try to get by on just under $9,000 per year from the province and less than $300 per year in the form of quarterly GST rebates from the federal government. If that person had a child, their benefits would jump to over $20,000 per year. (AISH, for comparison, provides just under $24,000 per year to a lone parent with two children.)

In other words, the drive to provide social assistance via child benefits, while politically attractive, has meant largely abandoning single people and couples without children.

The Notley government, in addition to indexing income support to inflation, increased rates for both AW and AISH. Albertans without children (expected to work; in private housing), for example, saw their monthly support through AW increase from $627 to $745. An AISH recipient in the same situation saw their monthly cheque go from $997 to $1,293. Benefits had not been increased in Alberta since 2009.

These amounts, however, remain sadly inadequate. In real dollars the Alberta Works rate is less than an unemployed Albertan (single; considered employable) would have received in the early 1990s, while housing costs have risen much faster than inflation. And the problem of inadequate income support for people without children is likely to worsen. Alberta’s economy is undergoing a great deal of change. The oil and gas sector is shrinking and is unlikely to recover to past employment levels. This sort of industrial readjustment can be disastrous for middle-aged people whose schooling and skills make retraining for an equivalent career unlikely. To subject them to extremely low levels of support because they are single or don’t have children is a failure of the social safety net.

Because governments, including Alberta’s, have abandoned single people when it comes to income support, many of them are forced to rely on emergency homeless shelters. The vast majority of shelter users in Alberta are single males. The combination of a very low level of income support and high rents is a key driver of single people into homelessness.

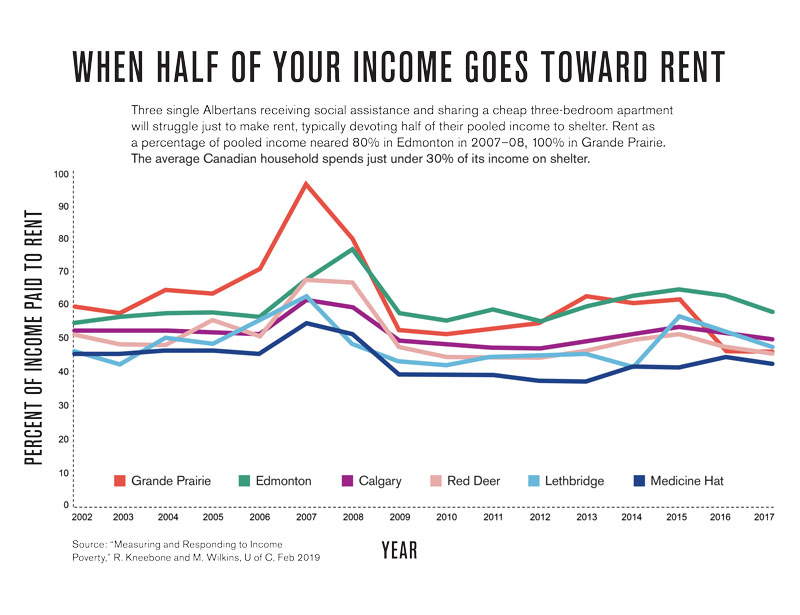

Income support in Alberta is also not sensitive to where one lives. An individual or a family receives the same level of support whether they live in Calgary or in rural Alberta. This is important because the cost of living in Calgary, especially for housing (the largest element of most household budgets), is much higher than in most Alberta communities.

In her research for the School of Public Policy, Margarita Wilkins refers to this as the “small town advantage” of social assistance. She calculates that a lone parent with one child receiving social assistance and living in a one-bedroom apartment in Medicine Hat is able to devote an extra $250 per month toward food, utilities and other necessities relative to what she could spend were she in Calgary. This difference could encourage social assistance recipients to remain in smaller communities, away from employment opportunities, or force those in large cities to make hard choices between paying rent, utilities or food. Social assistance benefits could be made sensitive to local costs of living; the cost of such an effort is surprisingly modest.

Making adequate income support dependent on a recipient having children is bad policy. So long as the federal government prefers merely to expand child benefits, change will fall to the provinces. Addressing deep poverty and homelessness requires that Alberta increase its support to the nearly three-quarters of Alberta Works clients who don’t have children. Likewise, we must make income support sensitive to local costs of living, so that recipients aren’t dissuaded from living in cities, where there are more jobs.

Both efforts would better honour our society’s commitment to help those fellow citizens in greatest need. In the meantime it will be left to the rest of the social safety net—including charities and other non-government organizations—to fill the holes.

Ronald Kneebone is scientific director of social policy and health and a professor of economics at the U of C.