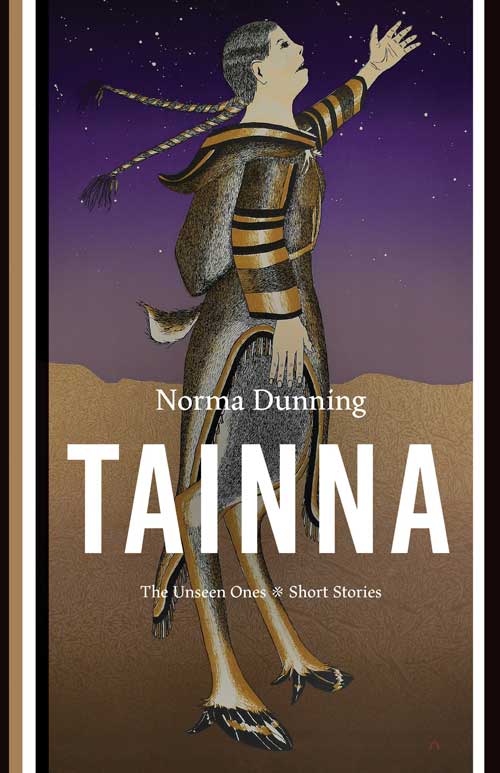

Norma Dunning’s Tainna: The Unseen Ones picks up many of the themes of her prizewinning debut, Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, but these six new stories have even more of an edge. The lives of the Inuk characters are hard, and many of these stories are filled with harsh language that emphasizes the characters’ difficulties.

In what I think is the saddest story, “Kunak,” the title character lives with his grandfather Chevy, a wildlife guide. One day Chevy disappears while out on the land with hunters. Kunak is 14 and alone. Dunning delineates how his life falls apart. The women of the North can leave with men from the South, but “Inuk men found their Southern Comfort in other ways.” No one has an easy transition, as the traditional ways have vanished along with a sense of identity and purpose, and there’s little to replace them. Kunak ends up panhandling on the streets in Edmonton, suffering from alcohol abuse and loneliness. Dunning does a stellar job of showing Kunak’s life from his perspective, revealing him as a complex human being with many powerful emotions and desires. Unfortunately, his life has been shattered by things beyond his control.

“Panem et Circenses” is one of the most disturbing stories I’ve read in a long time. Some aging rich women sit around drinking, hoping to attract the attention of an even richer man. This story is Juvenalian satire at its most vicious. The women are compared to “cobras in a charmer’s basket, weaving their heads at the stranger among them.” One of the women is from Iqaluit, and a man trolling for a companion asks her the inevitable question: “Did you ever eat raw meat?” Her answer gives a sense of the tone pervading these stories: “If I can chew and swallow that stuff, baby, I can chew and swallow anything.” When the man leaves, the other women turn on their companion from the North: “We’ve kept your brown skin and eyes around so we don’t appear racist. It’s politically responsible and now… look at you, thinking that you’re somebody. Know your place!”

“Tainna (The Unseen Ones)” delves into the issue of missing and murdered women and how so little is done to protect them or even to find out who they were. It’s a challenge to find light in these stories, though in “These Old Bones” Dunning returns to her character Annie Muktuk, who is still coping with the trauma of her past but has found some solace through art. She’s moved to Vancouver Island to be close to her son and managed to create a quiet life—after decades of violence and anguish.

In capturing the humanity and the pain of her characters, Dunning shows why real change is going to take compassion and time. But these stories offer insight and that’s a good start.

Candace Fertile teaches English at Victoria’s Camosun College.

Click here to sign up for our free online newsletter.