Pickup trucks are hardly a rare sight in Alberta, but they approach the level of standard accessory on the streets and in the work camps of Fort McMurray. So it’s doubtful that the convoy of seven white trucks heading out to Shell’s Albian Sands mine drew much attention, even with their orange warning flags waving and amber rooftop lights slowly turning, even when they began bumping across the muddy expanse of the mine itself. But then they parked.

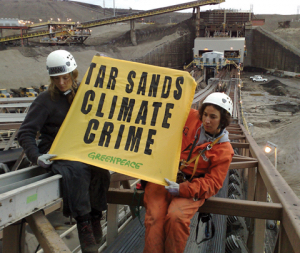

From the train of vehicles came some 25 people, clothed in orange jumpsuits and humping backpacks stuffed with chains and banners. They set up a perimeter, scaled a four-storey dump truck loaded with bituminous sands, and unfurled, bungee-corded and waved their signs. They wrapped chains around their vehicles and their bodies, snapped the locks and waited. And then came the attention.

Greenpeace’s September 15, 2009, action at Albian—and its subsequent, equally high-profile actions at Suncor’s Fort McMurray operation on September 30 and the Scotford upgrader near Fort Saskatchewan on October 3—was hardly unprecedented for social and environmental movements in general and for Greenpeace specifically. But these types of acts of civil disobedience are virtually unheard of in Alberta, and certainly mark the first time any group has tried such tactics in the debate on the oil sands, the mammoth project that has come to dominate, if not outright define, Alberta’s political, economic and environmental climate over the past decade.

That much could be surmised from the Alberta government’s initial response: in the wake of the actions, Premier Ed Stelmach and then-Solicitor General Fred Lindsay made noise about seeking tough sentences. Lawyer Brian Beresh expressed concern that Stelmach was trying to use his position as premier to exert influence over the judicial system and undermine activists’ right to a fair trial. (Proceedings are moving slowly for the 37 activists charged: no case has yet made it to court.)

Mike Hudema’s methods seem fueled by suspicion of more conventional forms of civic engagement.

Formed in 2007, the local iteration of the notorious inter-national environmental group physically occupies only one site permanently: a nondescript warehouse in a light-industrial strip along Edmonton’s Calgary Trail. Their psychological footprint is much bigger: almost immediately after they set down roots in Alberta, they began grabbing headlines with daring media stunts.

In November 2007, a team of activists rappelled from Edmonton’s High Level bridge and unfurled two banners that have since become posters for their activities: both black, one features a crude white outline of the province, red paint splattered like blood in the location of various oil sands developments, while the other simply proclaims “STOP THE TAR SANDS” in giant white letters.

The next April, Greenpeace dropped in, literally, on the annual Premier’s Dinner in Edmonton, rappelling from the ceiling as onlookers gasped and unfurling another banner, this one reading “$telmach: the best Premier oil money can buy.”

A few days later, some 1,600 ducks unwittingly landed on one of the tailings ponds at Syncrude’s Aurora North site; most drowned in the oily waste. Greenpeace began showing up on oil company property. In July 2008, Greenpeace slipped past security at the same Syncrude pond and placed banners overtop a tailings outflow pipe featuring a skull and crossbones and a message urging Alberta to stop developing the tar sands.

Syncrude was eventually charged under the Alberta Environmental Protection & Enhancement Act and under the federal Migratory Birds Convention Act. At the beginning of their trial in March 2010, after Stelmach told a reporter that he hadn’t yet seen photos of the ducks, Greenpeace showed up at the Legislature to present the premier with giant, gift-wrapped pictures of the oil-soaked birds.

In between all of these actions, Greenpeace staged more-conventional protests on the Legislature steps, outside corporate head offices and even at government-sponsored pancake breakfasts. In short, in the three years since they opened an office in Alberta, Greenpeace has become one of the most consistent and high-profile voices against oil sands development.

But while few will dispute that they’ve been effective at drawing the spotlight to the oil sands in general and to their own actions in particular, just what that means for their goal of actually stopping the oil sands is less clear.

“If you’re at A and you’re trying to get to B, you need to have someone screaming for C.”—Marlo Raynolds

“I’m sure there’s more than one effect, and I’m sure they’re conflicting effects,” says Dr. Laurie Adkin, a political science professor at the University of Alberta and expert on environmental movements and democratic citizenship. “Greenpeace’s actions have definitely brought more international and national attention to this issue,” she says. “But more media attention is always kind of ambiguous, how that plays out politically. On the negative side, some people will feel antagonized, will feel more hostile to Greenpeace and environmentalists in general, because they feel this act is embarrassing the province somehow.”

Put another way, headlines do not always translate into policy changes, and in going to such extreme lengths to bring attention to the issue, Greenpeace may be letting its medium overwhelm its message. That said, it’s probably wrong to assume that the Alberta public truly understands what Greenpeace is doing. There may in fact be more method to Greenpeace’s “madness” than immediately meets the eye.

In a time of almost unprecedented political apathy in Alberta, when a person who casts a vote is in the minority, people who chain themselves to the industrial machinery that fills the government coffers might as well be aliens. Mike Hudema, however, was actually born in Medicine Hat and, save a brief stint working for an NGO in San Francisco, has spent his entire life studying and working in this province. For the last three years, his job has been to head up Greenpeace’s Alberta chapter as their climate and energy campaigner, and so is as responsible as anyone for the tactics Greenpeace employs to spread their message about the environmental effects of oil sands development.

Knowing Hudema’s past, the headline-grabbing stunts come as little surprise. Though he initially attended the University of Alberta for a business degree, he completed a bachelor of education in drama and eventually a law degree. He quickly made a name for himself: at a 2002 university board of governors meeting, activists showed up to protest tuition hikes waving signs and dressed in outrageous costumes—Hudema wore a chicken suit. On the strength of that notoriety, he ran for students’ union president that year—though by his own admission he had no intention of winning, viewing the campaign instead as a platform to criticize student council. His criticisms were evidently shared by voters: he was unexpectedly elected.

Even in that position of power, Hudema was not a quiet or conventional president: he stirred up controversy in his orientation speech, calling on first-year students to get active at an event that was typically a boosterish celebration, and invited the media to witness him paying his tuition by rolling wheelbarrows full of coins to the cashier’s window.

Hudema has not moved far from the university, literally or figuratively. His small house—six blocks from the U of A campus on a street characteristic of Edmonton’s tree-lined and quiet older neighbourhoods—sticks out for its decoration. In the corner of one picture window is a poster of Ed Stelmach, his eyes fixed in an ominous Children of the Corn-esque gaze overtop the words “The EUB is watching you.” In another window sits a “Free Tibet” sign. A familiar sticker on the mailbox asking for no junk mail is dwarfed by a pair of Greenpeace stickers calling for an end to the tar sands, lest the postal worker wonder where the house stands on the issue.

The interior is no less strident: the famous picture of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists at the 1968 Summer Olympics is flanked by a red-splattered Stop the Tar Sands poster and the two banners from the High Level bridge protest. A Diego Rivera print hangs on the other wall. Not evident in his living room is Hudema’s fondness for Jack Kerouac (“The only people for me are the mad ones…”) and Arundhati Roy (“Not only is another world possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing”), both of whom he quotes in his email signature.

Despite outward appearances—the day we met, he was wearing a T-shirt urging support for the Lubicon Cree—Hudema is calm and measured in conversation. One on one, at least, he is something like an anti-demagogue; he fights to contain emotion and sentiment and seems to use sound-bite quotes and an officious, debater’s voice to hide what’s going on under the surface. This is an ability that no doubt serves him well when speaking with one of the many outraged citizens who call him to complain in the wake of another action.

Keyed into the right topic, though—Hudema’s experiences meeting with cancer-stricken residents in Fort Chipewyan, say, or how he felt standing in the Albian Sands’ black expanse with a few dozen other people who “care enough about what’s happening to stand up,” as he puts it—and his voice has a low crackle, his breathing becomes heavier, his eyes lock in an unwavering intensity. It’s at moments like this that the reason for his commitment is apparent: this is a man who can’t just see an injustice, he feels it.

“I work for Greenpeace, which is known as an environmental organization, but I try as much as possible to also approach activism from a social justice perspective: what are the human impacts of developments, what’s being done to communities?” Hudema says. “I don’t really see too much of a line, to be honest. To make a distinction between protecting the environment and protecting human societies, to me is a false dichotomy.”

Hudema stands out among local activists. A survey of NGO workers and volunteers would no doubt turn up people with just as much conviction (if not as many posters), but Hudema’s unique methods seem fuelled by a suspicion of more conventional forms of civic engagement. Hudema doesn’t spell it out as such, exactly, but he does make frequent mention of a democratic system that “doesn’t ever really encourage our participation” and the internal pressures that prevent people in government and industry from rocking the boat.

“There are a lot of good people that work in the system. It’s not that there aren’t good lawyers out there or good bureaucrats or people in industry that really want much more substantial change. It’s just that they don’t have much room to move,” he says. “There isn’t that greater social pressure that gives them much more space to demand bolder things. They can only demand these very small steps, rather than big leaps and bounds. I see my role as trying to make that space possible. I think I’m more useful trying to create that outside pressure, because I don’t see that much room for movement working internally.”

That’s a position that U of A professor Adkin can understand coming from an environmental group in this province.

“Most environmental organizations in Alberta have had a very long and dismal experience of trying to participate in consultation processes in which the terms of reference are set by the government, the panels of stakeholders are appointed by the government and the outcomes of consensus are not necessarily going to be implemented,” she says. “They’ve had many more experiences of a pretense of democratic process than real forms of meaningful input.”

Not that this fact endears Greenpeace to many people in Alberta. One need only consult the comment sections of online news stories to sample the hostility they engender: though the group does have its defenders, the comments tend toward the negative, ranging from people imploring the government to “run down” or “jail” the “eco-terrorists” and “jobless hippies” to people sympathetic to Greenpeace’s environmental goals but who accuse the organization of grandstanding or caring more about getting their name out than really trying to change oil sands policy.

Still, Greenpeace does have some support among people who work on environmental issues in Alberta. While the Pembina Institute shares similar ideas about the need for environmental stewardship, you’d be hard pressed to find a group more dissimilar in their methods to Greenpeace than the Calgary-based environmental and energy issues think tank (notably, Pembina stops well short of calling for a shutdown of the oil sands). Headlines are harder to find for Pembina’s work, though, which is largely devoted to participating in government consultations and publishing reports on topics such as oil sands pipelines and Canada’s largest greenhouse gas emitters.

Pembina’s executive director, Marlo Raynolds, describes the think tank as a “bridging organization” between governments, NGOs and corporations, aimed at establishing a consensus solution on environmental issues. And he only sees that work aided by some of Greenpeace’s extreme tactics. “I’m a strong believer in the theory of ABC,” he says. “If you’re at A and you’re trying to get to B, you need to have someone screaming for C.”

Raynolds understands this first-hand: as a veteran of many multi-stakeholder committees set up by the Alberta government, he’s been frustrated by a lack of action on environmental regulation—especially after many of these committees were able to produce consensus recommendations endorsed by industry, environmental groups and affected communities. For him, more awareness of oil sands issues will only increase pressure on the government to stop ignoring input, and will only create the political will to move forward.

“I think it’s so important to recognize that there’s a spectrum in any movement. Greenpeace does an incredible amount of valuable work in terms of shining the spotlight on big issues,” Raynolds says. “Once the spotlight is on something or someone or a company, often those entities are forced to react, or at least think, and this provides space for organizations like ours to put some ideas on the table for solutions.”

Raynolds points out that Greenpeace does similar work to Pembina, commissioning reports and conducting research, but says Greenpeace’s lower-profile activities tend to get overshadowed by their stunts. One such report is “Green Jobs: It’s Time To Build Alberta’s Future,” co-commissioned by Greenpeace, the Sierra Club and the Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL), which focuses on the economic benefits of sustainable energy development. “Green Jobs” is a comprehensive and forward-thinking document that seeks to prove one of Greenpeace’s fundamental arguments about oil sands development: that economic prosperity and environmental stewardship needn’t be mutually exclusive.

70% of Albertans support slowing down oil sands development: Pembina.

However, it was also the result of a collaboration that’s not likely to be repeated anytime soon. The report was published a few months before Greenpeace’s actions in Fort McMurray and Fort Saskatchewan—actions that, according to AFL president Gil McGowan, soured many of his organization’s members on working with Greenpeace in the future.

“Thousands of construction workers, many of whom are members of unions affiliated with our unions, weren’t able to go to work that day. Many of those people were left harbouring angry feelings toward Greenpeace. That’s going to make it more difficult for us to work with Greenpeace in the future,” McGowan says. “On one hand, they’re deliberately taking positions that some could characterize as extreme in order to broaden the debate; on the other hand, by taking those positions they run the risk of alienating individuals and groups who might otherwise be their allies.”

And while McGowan says that the AFL certainly wouldn’t rule out working with other environmental groups in the future, he notes the risk that Greenpeace’s actions are diminishing the voice of the whole. Like it or not, not everyone in the province is especially attuned to the subtleties of the environmental movement, and the fact that Greenpeace’s actions are on the nightly news while other groups toil behind the scenes can create an impression among the public that the entirety of the environmental movement is as radical as Greenpeace.

Raynolds has found this to be true with Pembina. He hopes that as environmental issues are pushed to the forefront of public consciousness, more people will be able to differentiate between groups. “It’s a serious problem, but [the confusion] is mostly from people who don’t take the time to understand the differences between organizations and approaches: they see one group and they make up their mind about the whole environmental movement,” he says. “I think that’s evolving, though. It only takes [interacting with different organizations] once to see that the groups are very different.”

For Greenpeace’s part, these are drawbacks they understand. Bruce Cox, executive director of Greenpeace Canada, says that the implications of each action are carefully considered. He considers awareness of the problems—especially on a national and international level—to be the higher goal: “For every person that might take umbrage at a direct action or act of civil disobedience… there are probably 50 people out there who learned about the problem for the first time.”

Hudema, meanwhile, points to the urgency of the issue of climate change as sufficient justification for any blowback that may come Greenpeace’s way. “A lot of our recent activities [were motivated by] the fact that 300,000 people on average die every year because of climate change. That’s the UN’s own figures,” he says, his voice wavering. “It really is a life-and-death situation for a lot of people around the world, and a lot of people downstream in this province. If you’ve seen people go through cancer, I think it justifies a peaceful protest that maybe shuts down an oil sands operation for six hours. I think that’s more than justified.”

However, whether more such actions are justified remains to be seen. All sides agree that the environmental cost of oil sands development is attracting more and more attention, both at home and worldwide. Partially thanks to Greenpeace’s global network of activists, protests about the oil sands have started in countries far removed from Alberta, including demonstrations in Washington, DC, and an occupation of a Total refinery in France. Consumers of oil sands oil have started to question its overall cost. Some 850 American mayors signed a resolution to avoid using high-carbon fuels in municipal vehicles. Retail giants such as Whole Foods and Bed, Bath & Beyond announced in February that they would look for alternatives to oil sands fuel for their fleets. A recent survey commissioned by the Pembina Institute shows that more than 70 per cent of Albertans support slowing down oil sands development.

The space Hudema talks of creating seems to be coming. That, says Adkin, will leave Greenpeace with some important questions about their own role. When citizens, environmental groups and think tanks are able to get industry and government to sit down and reach a consensus about some of Alberta’s most important environmental issues, when all sides are finally willing to achieve a compromise, it remains to be seen what if any role Greenpeace can play.

“I think on one hand they really have to think hard about their tactics in relation to their goals, and what’s possible to achieve and how they can achieve it,” Adkin says. “On the other hand, they can’t simply set aside their principles and their own understanding of what’s at stake. They have to reconcile these ideas; to be tactical without being co-opted, without being compromised so that in the end they don’t achieve very much either. It’s a difficult game for them.”

David Berry is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Edmonton. He is also an entertainment correspondent for Global TV.