The American electorate is torn between a polarized two-party system on the one hand and the dangerous allure of systemic disruption on the other. The tech industry has already roiled most of post-war capitalism. What happens when the tech-bros turn to politics?

Andrew Yang and Stephen Marche’s disruptor-in-chief is the apotheosis of American meritocracy. Cooper Sherman is a centrist populist with big ideas. Unlike Trump, who exudes cynicism, this man truly believes he is a force for good. And just like some other billionaires, he’s a walking, talking illustration of the Dunning-Kruger effect: a man with limited experience overestimating his own abilities.

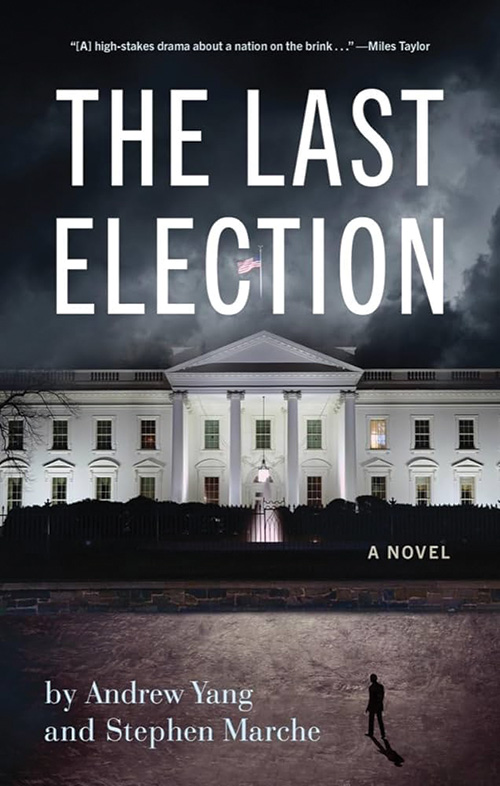

A defining characteristic of the successful political thriller is that its authors are almost as interesting as the conspiracies they invent. Yang was a memorable candidate in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries and brings an insider’s perspective. Edmonton-raised Stephen Marche made a name with a book of speculative non-fiction about American social breakdown, The Next Civil War.

Where The Next Civil War was chilling, The Last Election is winking and wonkish. Characters are sketchy: both ethically compromised and poorly drawn. And that is by design. As the end approaches, narcissism and naked ambition limit self-actualization. Everyone feels the prickle of dread, but nobody knows the score. “The political condition of the United States is so toxic… that the suspicion of a great shock coming has morphed into a common expectation.”

This is the sort of novel plotted by political science graduate students after a night of absinthe, but its melodrama is the right tone for politics today. In The Last Election, the end of American democracy comes through the arcane byways of the US constitution and the machinations of unnamed villains among the Joint Chiefs of Staff. But the real antagonist is the system itself, a ponderous thing designed for stability in the 19th century and too easily subverted by ambitious patricians today.

On the face of it, the plot is absurd. But is it any more preposterous than everything that’s happened in the past decade? Not really. What’s more, the tawdriness of unsubtle conspiracy doesn’t detract from the reading experience, because the surreal is where we live now.

I don’t want to damn with invidious comparison, but this novel reminds me of The Handmaid’s Tale. Everything Margaret Atwood wrote about in 1985 has happened before and since. It’s much the same for this novel. In fact, most of the ground covered has already been documented by concerned academics in books such as How Civil Wars Start, by Barbara F. Walter, and White Rural Rage, by Tom Schaller and Paul Waldman.

As the reader charges towards election day, our populist candidate gives voice to the dread at the heart of polarized politics: “We are on the cusp of our civilization rising to a new level of mass prosperity and renewed dignity of the individual, or collapsing into the horrors of a few secretive rulers holding all the money and all the power and all the say.” This is indeed our fear: that an impending crisis of techno-feudalism will be hastened by the delegitimation of democracy.

In this, the worst of all possible worlds, there is no institutional fix for simmering rage. And the intensity of emotion is now part of the problem. Voters sense looming disaster and choose a big man to shadow-box with unseen foes. That they are to blame for the destruction of their own democracy is meaningless as the noose pulls tighter. I won’t tell you how it all ends, because you already know. This is the last election before whatever comes next.

Marc D. Froese is a professor of political science and the director of International Studies at Burman University.

_______________________________________