I was 18 when my family first bought toilet paper. Don’t get the wrong idea. We knew the merits of cleaning oneself after a trip to the bathroom. It’s just that for the first 18 years of my life we never had to purchase toilet paper. Or butter. Or a number of other household items. I grew up on an army base. Dad served 28 years in the Canadian Armed Forces and every month or so he would come home with a box of toilet paper in the trunk of his car. Or a case of butter. And it didn’t stop there. Our bed sheets, blankets and even our olive green curtains were all monogrammed with the initials DND (Department of National Defence, for you civvies out there). When we went camping, we slept on army air mattresses while snuggled in army sleeping bags. And instead of building a rec room in the basement like many parents did in the ‘70s, dad created a space for us by draping his parachute from the ceiling. The parachute was orange and white and polyester, and since it was the ‘70s we had the coolest rec room in the neighbourhood.

Again, don’t get me wrong. Dad’s pilfering was commonplace in the PMQs (Personal Married Quarters, again for you civvies). In fact, dad’s borrowing of goods (I say borrowing because he returned much of the bedding, his uniform and that parachute when he retired) was extremely minor compared to what others did. One guy I knew had a special room in his basement, filled floor to ceiling with canned goods, like a miniature Costco warehouse. His dad was a cook. Compared to other families in the military, we were pretty lucky. In the first nine years of my life, we moved three times: Edmonton to Germany, back to Edmonton, and then to Calgary, where we stayed at the old Currie Barracks for nine more years until dad retired from the forces at the ripe old age of 46. Staying in one stop for such a long time was rare. Many of my friends moved every two or three years. Larry, Randy, Greg, Mike, Graham, Skeeter, Walter, Allan, Zurch—the names of best friends for year or two, and then one of us would be gone, never to be seen or heard from again.

While some fathers were gone for six months on peace-keeping missions to Cyprus, the Golan Heights and other exotic locales, dad was gone an average eight weeks out of every year. Sometimes, during a bugout, he left without warning. There would be a call in the middle of the night and he was dressed and gone in less than 15 minutes. Sometimes we never heard him leave. We’d come down for breakfast and dad wasn’t in his usual spot at the kitchen table, drinking his coffee and trying his combat boots. “Bugout,” was all mom had to say and we knew.

We were in Germany when Russia invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, and even though I was really young at the time I remember air raid sirens echoing in the night, a heavy knock on the door and dad gone without any contact for several days. There was another time, after dad came home from the FLQ crisis in Quebec, and we were looking at photos in a magazine. There was one shot of formidable looking soldiers, armed with semi-automatic weapons, on the roof of a church during Pierre Laporte’s funeral. The caption said the soldiers had shoot-to-kill orders for anyone they deemed a threat. “Hey that’s me,” dad said with a smile, pointing at one of the heavily armed soldiers. I realized then my father’s job had life and death consequences.

It was a company town, the army base. And even bases like Currie Barracks, surrounded by Calgary suburbs and only a 15 minute bus ride to downtown, had that small town feel. Everybody knew pretty much everything about everybody. If you got a new dog that barked too much, people knew. If you called the MPs because your neighbour’s dog barked too much, people knew. If somebody’s daughter got pregnant; people knew. And they usually knew who the father of the baby was. If your dad didn’t drive you to hockey because he was always drinking at the Mess, people knew. If your family was getting posted somewhere across the country, people knew. It was an insular place, rife with rumours and gossip, with a solid suspicion of outsiders.

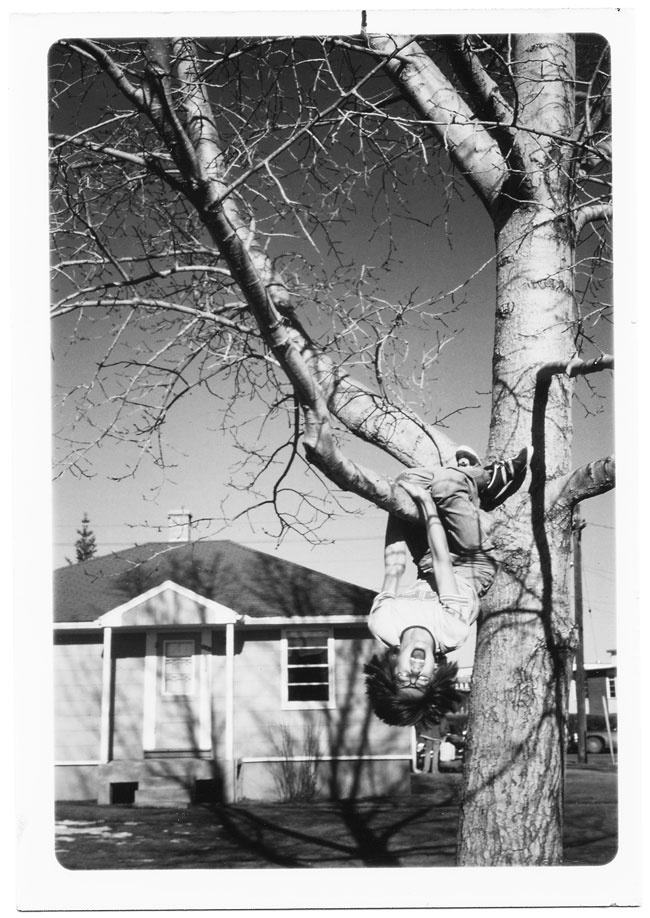

Still, it created a tight-knit community, especially among us army brats. Bullies were rare because the father of the person being bullied could be the co (Commanding Officer) of the father of the bully. And the constant moving, or the constant threat of moving, ensured that cliques were few. You made friends quickly, even shy people like me, because you had to, or because the more gregarious kids forced you to be their new friends.

Only when we moved up into the city high school and mixed with civvie kids—a few of them believe we were trained in various military techniques and martial arts like our dads, and we did nothing to refute those beliefs—did we graduate into various clique. But there was a difference: a civvie jock would never, ever talk to a civvie geek on a friendly basis. Their lines of social demarcation had been drawn and supported for years. But an army brat jock would talk to an army brat geek because there was a bond, a connection that couldn’t be severed by the intensity of adolescent peer pressure.

Even now, more than 20 years after my dad left the forces, the bond remains. We’ve all grown up, moved to various parts of the country and worked in a variety of fields and occupations. Some followed their father’s footsteps and joined up, serving in Somalia, Bosnia, Afghanistan and other hot spots. Some still keep in contact with old friends. But others, like me, have lost touch with most of their old army base friends and have no dealings with anything military. But whenever I meet someone who grew up on an army base, there’s always that special smile, that look of recognition and the quick exchange of information: the bases we lived on and our father’s rank duties. And if we have time—and we usually make the time—we share out stories, those tales that tie us together, even though we may be perfect strangers. Because one thing always remains—once an army brat, always an army brat.

Wayne Arthurson is the author of Final Season, Thistledown Press, 2002, He lives and writes among the civvies in Edmonton.