When the Secret Elevator Experimental Performance Festival was held in Calgary in 1987, a few audience members at a time stepped into an elevator in the Soma building downtown and rode up to an office to see the shows. Thirty years later, the High Performance Rodeo International Festival of Performing Arts, a direct descendant of the tiny original Secret Elevator festival, brings innovative theatre, dance, music and art to stages across Calgary every January. Nowadays, the festival presents 25 to 30 shows (80 performances) to a sit-down audience of up to 20,000.

Martin Morrow, a former Calgary arts journalist and theatre critic who now works in Toronto, says of that evolution: “The Rodeo started out as a tiny little thing that nobody knew where it was going, and it grew into an international event. That’s kind of amazing.”

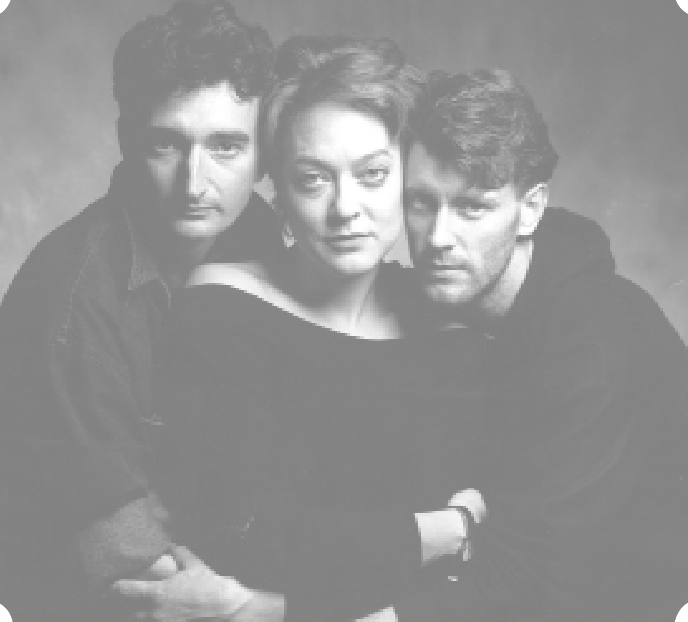

Behind the High Performance Rodeo (HPR) stands the experimental theatre company One Yellow Rabbit (OYR), founded in 1982. One Yellow Rabbit was able to create something as enormous as the Rodeo by inviting other Calgary arts organizations to join in. The first time Theatre Calgary presented a Rodeo presentation on its stage in 2009, its artistic director, Dennis Garnhum, told the Max Bell Theatre audience that he was thrilled to finally be working with the “cool kids.” He meant Blake Brooker and Michael Green, OYR’s founders, and the core ensemble of friends who’d joined them and stayed: dancer and choreographer Denise Clarke, composer and sound designer Richard McDowell and actor Andy Curtis.

None of the Rabbits were professionally trained theatre artists. In the book Wild Theatre: The History of One Yellow Rabbit, Morrow’s account of OYR’s first 20 years, he describes them as a guy into avant garde performance art (Green), a poet (Brooker), a ballerina (Clarke) and a punk-rock musician (McDowell). “They figured out a way of meshing their performance art and poetry and dance in a way that was unique to them,” he says. “It was unusual in that it was all gathered under the umbrella of theatre but none of them were actually theatre people at all.”

Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. “That’s exactly how One Yellow Rabbit became a success,” Morrow says. “They weren’t afraid to fail.”

OYR’s core group of artists stuck together through a variety of financial crises. They also held together when Brooker and Clarke divorced. But in the last 13 months the tight-knit group has had to deal with the most permanent kind of separation. Richard McDowell died suddenly of a heart attack in November 2014. Less than three months later, in February 2015, Michael Green was killed in a car accident in Saskatchewan, along with Blackfoot elder, writer and filmmaker Narcisse Blood and Regina artists Lacy Morin-Desjarlais and Michele Sereda. Green and Blood had been working on Making Treaty 7, a groundbreaking collaboration between First Nations and non-First Nations in southern Alberta.

“The Rodeo started out as a tiny little thing that nobody knew where it was going, and it grew into an international event.”—Martin Morrow

At a public memorial for Green that filled Calgary’s Jack Singer Concert Hall, Brooker shared stories about late nights in hotel rooms around the world. He told about how Green had always been “drawn to the different, the outlandish, the larger than life.”

Brooker and Green met in the late 1970s at Ikarus, an amateur theatre company started by former drama students at Western Canada High School. They were putting on shows in abandoned houses and other makeshift locations. Brooker recalls that Ikarus was successful at getting people out to see its shows but made no money. Brooker and Green decided to start a professional theatre company and pay themselves. Brooker came up with the name. “My oldest stuffed animal was a rabbit. He was a plush rabbit, but he got rather un-plush, and, at some point, I think my mother made a suit for him. It was yellow. That’s the Rosebud backstory.”

OYR showed up on Morrow’s radar when he was an entertainment writer for the Calgary Herald. Morrow attended OYR’s 1984 performance of Leonardo’s Last Supper, by Peter Barnes, in which a family of undertakers have fallen on hard times until the corpse of Leonardo da Vinci arrives. They think they are saved until Leonardo turns out to be alive. Morrow described the play as a “shit-and-vomit bespattered comedy” that no other local company would have staged at the time. “I was expecting typical but ambitious, amateurish theatre. (I) was blown away.” When Morrow became the Herald’s theatre critic in 1988, he watched OYR closely. “I thought, we’ve got to start paying attention. These guys might be going somewhere.”

OYR fulfilled that promise when it started producing its own work. A play called Alien Bait was about alien abductions. With the audience expecting satire, Green made a serious attempt to understand people who are convinced they have been abducted. “It was funny—I mean, it was One Yellow Rabbit—but there was also some really insightful stuff.” Morrow recalls a “moving and harrowing” monologue by Green as a man describing his abduction. “(Green) transformed what would normally be a joke into a guy expressing a terrible trauma that nobody would take seriously.”

When OYR formed, the theatre scene in Calgary consisted of what Denise Clarke calls “artists doing Shakespeare with British accents.” Alberta pioneers such as Sharon Pollock and John Murrell were also writing new work, which laid the groundwork for the Rabbits. “When we came along,” says Clarke, “we wanted to create a new, devised work where you would focus on an ensemble of artists, much like a rock band.” OYR created more than 30 original works, including Doing Leonard Cohen, Dream Machine, Featherland, The History of Wild Theatre and Mata Hari: Tigress at the City Gates. The company toured Canada and went abroad: the US, Mexico, Europe, Australia.

Clarke was associate director and remembers having a lot of fun. “We were out and about, and we understood that we were really fucking good, and the work was interesting and smart and funny.” As punks with a DIY aesthetic, they weren’t afraid to push the boundaries. “We come from the avant garde, so when we were kids, anything went.”

With that attitude came controversy. The Batman on a Dime, a superhero parody, was described in the Edmonton Fringe Festival’s guide as an “X-rated mini-musical” for its nudity and sexual content. Crowds lined up for it at the Fringe but, a year later, the same play proved too much for Expo ’86 and was shut down. Plans for an Edmonton run of the musical Ilsa, Queen of the Nazi Love Camp had to be abandoned when a judge ruled it might prejudice the jury in a retrial of holocaust denier Jim Keegstra. In the play, Nazi officers are searching for Hitler’s lost son (created from preserved sperm). The trail leads to Keegstra’s hometown of Eckville, Alberta, and the Nazis are indignant when they learn the school teacher denies the Holocaust ever happened. After all, they’d been there.

Morrow says OYR’s antics and frequent nudity were “sincere and legitimate” artistic choices but were also good for publicity. “You can be the greatest theatre troupe in the world, and still, nobody will come and see you if you don’t find a way of attracting attention.”

That OYR made its home in Calgary was also significant. Brooker says in the early days it was difficult for local playwrights and actors to find work in Calgary. “(When) we started, we wanted to talk about here, because all the shit that came here was about somewhere else.” The company associated with like-minded artists such as Ronnie Burkett, Daniel MacIvor and Bruce McCulloch. It also mentored emerging talent through Clarke’s Summer Lab Intensive.

Calgary’s reputation as a haven of right-wing politics didn’t hurt either. “Whenever there’s a stronghold of conservatism,” says Clarke, “there’s a very strong underbelly. I’ve always fully believed that we couldn’t have been who we were without being from Calgary and Alberta.” Morrow says that, in return, the city provided an audience that valued OYR’s entrepreneurial spirit.

The High Performance Rodeo was Michael Green’s brainchild. He started it as a make-work project while the company was between venues and invited colleagues to come and experiment. “I called it a big laboratory,” Morrow says. “Certainly the stuff that was being done at the Rodeo at the time was very, very rough. Sometimes you’d get something fabulous, sometimes you’d get something that was just a waste of time. But the exciting thing was, you just didn’t know what you were getting.”

Morrow says Green was influenced by the “hungry energy” of performing artists coming out of New York. He convinced some of them, like Penny Arcade, to come to the Rodeo. “They showed where you could go with performance art and this type of alternative theatre. That threw down a gauntlet to local artists.”

The Rodeo was Green’s pet project for the first decade. That changed when OYR moved into the Big Secret Theatre. The company committed to creating a show for the Rodeo every year. After that, HPR “became something the whole company got excited about and really got behind,” says Clarke. “It just kept on expanding and turning into the kind of thing it is now: bigger acts, more international acts, more national acts. But we’ve still got the cool, weird show happening at the Legion.”

Brooker describes Green as “the face, the impresario, the Stu Hart” of the Rodeo. As its curator, he brought in high-profile artists such as Laurie Anderson, Phillip Glass, Marie Chouinard and Brian Eno. Those performers charged higher fees, so OYR started co-presenting with other companies. Vicky Stroich, executive director of Alberta Theatre Projects, says co-presenting with OYR at the Rodeo is a partnership that benefits both companies. They pool their resources to bring in a show they couldn’t afford separately, and “cross-pollinate” their audiences.

The “brash, loud and colourful” OYR has a great impact. “There was little beyond traditional theatre presented here. They changed the landscape.”—Clem Martini

“To look through the High Performance Rodeo program guide,” says Stroich, “is to see the very heart of collaboration in this city. The High Performance Rodeo is a great demonstration of just what we can do together as an arts scene in Calgary.”

Morrow agrees that Green worked to ensure there was always space in HPR for local talent. “I think Michael was always aware of the Rodeo’s roots. He was always looking for the most weird and edgy and unusual stuff that he could find because that’s where he came from.”

These days, One Yellow Rabbit is planning its future without two of its greatest friends. Posted on the website in July 2015 was the message: “We would like to express deep gratitude for all the beautiful acts of support and care that we received in the aftermath of our horrible winter…. We are moving towards the light that has been shown us.”

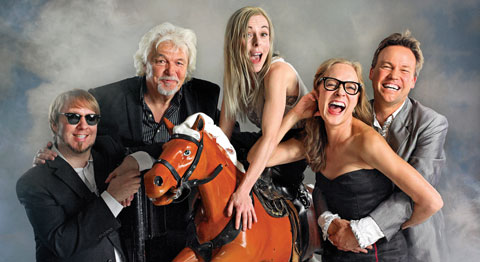

After taking time off, Denise Clarke returned with Radioheaded 3, her third movement-based performance to that band’s music, and presented it at the 2015 Sled Island Festival. Blake Brooker had planned a play for the next Rodeo called Casablanca, Casablanca, to be performed in Arabic, but says it was too sad. Everyone at OYR needed a laugh. Instead, he’s working on Calgary I Love You, But You’re Killing Me, a cabaret-style play about the city’s greed. “I mean, how much money do these pricks need? But it’s going to be a comedy,” he insists.

The next Rodeo will be in the capable hands of Ann Connors, whom Clarke credits with making OYR strong enough to survive the past year. Connors joined OYR in 2013 after six years at the Magnetic North Festival. She was already working with Green to produce the Rodeo, as he had taken a step back to work on Making Treaty 7. He was also returning to acting.

Clarke says that moving back to acting was the strongest focus Green had. “I think he was very comfortable with the Rodeo. He felt really good about Ann. He felt he could still do some of the curating and that it was going to be fairly seamless for him to work as an actor again.”

“He was one of the finest actors,” says Brooker. “A beautiful actor, very good at it. I loved working with him.”

Connors says the High Performance Rodeo will continue to work with local companies to present new and experimental work. The 30th anniversary lineup for January 2016 includes a new play called Huff, about life on First Nations reserves; Toronto theatre artist Evalyn Parry playing songs on a bicycle in SPIN; Calgary’s Ground Zero Theatre presenting its audio-only play Tomorrow’s Child to a blindfolded audience; the local debut of Who Killed Spalding Gray? by Daniel MacIvor, who was at the first rodeo; and more.

University of Calgary professor and playwright Clem Martini describes the Rodeo as a corridor between Calgary and the world. “It provided a forum for non-traditional works here within the city, and a forum for bringing in non-traditional works from across the country and internationally. That exposed the public to a different theatrical dialogue, and at the same time, those who came to present at the Rodeo saw what was happening here and it created an exchange.”

He says the company’s brand of “brash, loud, colourful, vibrant, fun theatre” has had a great impact on Calgary. “When they founded, there was little beyond traditional theatre presented here. They changed the landscape.”

As a playwright, Martini provided the final scene for Ilsa. As a professor, he brings OYR artists to work with U of C students. “You’d find a vast number of young people who went to One Yellow Rabbit and found inspiration on the stage, in the new vision they presented, in the kind of energy that was evident in the work they did.”

One Yellow Rabbit’s Calgary I Love You, But You’re Killing Me. (Trudie Lee)

Vicky Stroich was one of those people. “I remember going to the Uptown with my best friend, and my mom dropping us off, and watching this show with a naked Mark Bellamy and a naked Denise Clarke, dancing.” The show was 1994’s Breeder, a movement-based piece set in a dystopian future. “I remember seeing an energy in it and a sort of subversive sense of humour, but also a heart that was questioning ideas of gender and feminism and all those things that were just waking up for me. That show is the reason I pursued theatre,” Stroich says. “They made living in Calgary cool.”

At Green’s memorial, Bellamy, artistic director of Vertigo Theatre, said his life was changed when Green saw him onstage in musical dinner theatre and cast him in an OYR play. Green told him over and over that he was good enough, until Bellamy believed it. Many people have come forward in recent months to express their gratitude to One Yellow Rabbit, show their support for the artists in the wake of their recent loss and encourage them to continue their work.

Besides the tragedies, there have been some recent gains. Blake Brooker joined Denise Clarke as a member of the Order of Canada. Brooker also came to an important realization. “We wanted to do something here. And you know what—I only realized it with Michael’s death—I guess we did.”

Maureen McNamee is departments editor of Alberta Views and a long-time journalist with FFWD Weekly in Calgary.