A healthcare crisis is underway in every province across Canada and in countries around the world. The “why” is complex: a combination of pandemic overload and burnout among healthcare workers, demographic shifts in population and the healthcare workforce, bottlenecks and dysfunction rippling throughout a system that has failed to address a long-standing gap between the number of nurses, doctors and hospital beds we have and the number we need. This problem isn’t unique to Alberta, nor is the frequently proposed “solution”—to increase privatization. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a perfect opportunity to implement some of the bigger privatization plays.

Famously outlined by Noam Chomsky in a 2011 lecture at the University of Toronto titled “The State-Corporate Complex: A Threat to Freedom and Survival,” the privatization playbook is a guide to breaking public services and replacing them with market-based alternatives that prioritize profit over people: “There is a standard technique of privatization, namely defund what you want to privatize. Like when Thatcher wanted to [privatize] the railroads: first thing to do is defund them, then they don’t work and people get angry and they want a change. You say okay, privatize them—and then they get worse.”

Now, a new transformation of public healthcare has been set in motion by the United Conservative Party government. The roots of this latest battle can be traced back to the run-up to the 2019 provincial election, when Jason Kenney, at a press conference in an Edmonton seniors home, proudly gestured to an oversized posterboard sign. The sign was, Kenney promised, the last word on the “American-style” healthcare bogeyman; it was his promise that “a United Conservative Government will… maintain a universally accessibly [sic], publicly funded healthcare system.” The clues were there, between the awkwardly worded lines.

But the UCP privatization plan was never, from its inception, about “Americanization”—Albertans pulling out their credit cards to pay for medically necessary treatment. Rather, it is predicated on a more insidious transfer of wealth: maintaining publicly funded services that are increasingly delivered by private corporations. These, in turn, deliver profits to their owners and worse care to patients.

This strategy was spelled out in 2019’s McKinnon Report and Ernst & Young review of AHS (manufactured reviews designed to identify “problems” to facilitate the desired ideological “solutions”). It has been implemented through various initiatives and legislation over the last four years.

The strategy is part of a long campaign to reshape public healthcare into a tool of the market.

One of the UCP government’s first moves to create a larger market for private health companies was the passage of Bill 30 (an omnibus bill that would become the Health Statutes Amendments Act, 2020). It made changes to several health professional associations, including the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta (CPSA), which is tasked with oversight, regulation and approvals. The makeup of the CPSA was changed, with a new requirement for 50 per cent “public” participation. But “public” members are appointed by the government. The erosion of non-partisanship at the CPSA is designed to influence its role in approving “chartered” or “non-hospital”—private—surgical facilities.

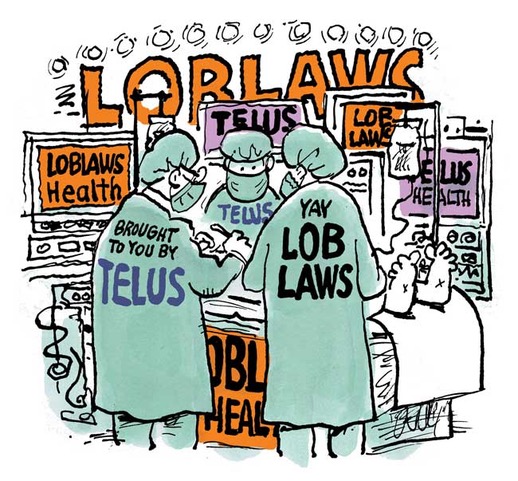

The bill also paves the way for further corporate involvement in healthcare delivery: more types of private corporations can now make agreements to directly bill Alberta Health for publicly funded medical services. This is crucial given the UCP government’s tearing up of the physicians contract in early 2020. It means that instead of having a collective agreement with Alberta Health, doctors can be bound to contracts with, say, Telus or Loblaw—both companies, through subsidiaries, employ healthcare workers to provide a mix of publicly and privately funded services.

At the beginning of the pandemic, for example, Telus Health, through the app formerly known as Babylon, benefited from a decision by then-health minister Tyler Shandro to allow private corporations to bill the government at a higher rate for “virtual” health services than family physicians in general practice can. And unlike the arbitrarily cancelled doctors contract, these corporate agreements have penalties built in that could dissuade future governments from cancelling these services or attempting to return them to public delivery.

The legislation also cuts approval times required for private surgical facilities and dilutes the oversight powers of the Health Quality Council of Alberta. These changes further blur the line between public funding and delivery, entrenching the framework for contracting out publicly funded surgeries established by the misnamed Healthcare Protection Act (Klein’s Bill 11) and expanding its scope. “Chartered surgical facilities” are so broadly defined in Alberta that a health minister can alter the parameters to suit a potential investor after a request for proposals is accepted. The Act also allows publicly insured and uninsured procedures to take place in the same facility, thereby enabling upselling and extra-billing. The UCP’s Health Statutes Amendments Act is not a mere slippery slope towards corporatized healthcare—it has actively written it into the Alberta system.

Along with corporatizing physician services, the UCP wants to cut nurses’ and other workers’ salaries.

Not content only to corporatize physician services, the UCP government also wants to cut salaries of nurses and other healthcare workers. In the February 12, 2022, edition of the Western Standard, then-Premier Jason Kenney boasted that outsourcing surgical procedures through the Alberta Surgical Initiative (ASI) would circumvent “union-run hospitals.” This is consistent with the UCP government’s wider moves to diminish the political and organizing power of unions through legislation. (The most odious examples include the 2019 Public Sector Wage Arbitration Deferral Act, which suspended a binding arbitration process for public sector bargaining, and the Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act, 2020, which enacted sweeping changes to the Alberta Labour Relations Code that limit the right to picket and the right to free association.)

Undermining unions is not a mere end in itself, however; it is a concerted strategy to replace unionized jobs with lower-paid, more precarious or automated positions. This was the impetus behind the UCP’s push to outsource nearly 11,000 jobs in laboratory services, medical laundry, housekeeping and food services—the very people who have been on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring testing and sanitation under the most challenging conditions. Research and frontline experience from BC, Ontario and the UK shows that when these positions are outsourced, workers are typically laid off, only to be rehired at a lower pay, with reduced benefits, precarious hours and more duties.

When corners are cut to save time and money, the risk of error, injury, and—in the case of housekeeping and laundry—the likelihood of infection increase. The UCP government disregarded a 2017 cost–benefit analysis conducted by the NDP government and awarded a province-wide laundry services contract to K-Bro Linen in April 2021. This, despite serious quality and safety concerns having been reported by media after that company took over services in Saskatchewan, such as linens coming back to healthcare facilities visibly stained and damaged and with used needles and surgical instruments folded inside bedding.

The Kenney government also began outsourcing food services in AHS facilities beginning in January 2022. This, just one year after the BC government brought their food services and housekeeping jobs back in-house, reversing a 20-year privatization policy that had disproportionately harmed the economic status of women and racialized workers in those roles. Studies of the Vancouver Health Region show outsourcing led to understaffing, inadequate cleaning practices and, ultimately, outbreaks of infection. The BC government said the policy reversal would improve wages and working conditions, which correlate to continuity and quality of care.

The next predictable aspect of the UCP privatization drive has been to invite system-wide service deterioration. One of the first decisions of the newly elected Kenney government was to cancel the Edmonton Hub Lab, at a cost of at least $35-million. This “superlab” on the U of A campus would have brought existing labs and staff under one roof to process more than 30 million medical tests annually. Coupled with the seemingly arbitrary change in 2019 to remove the word “public” from Alberta Public Laboratories (APL; now Alberta Precision Laboratories), the move demonstrated the UCP’s willingness to play politics with Albertans’ health; they had no qualms about incurring huge public costs for the sole purpose of undermining the public health system.

Over several decades at the centre of a public–private tug of war, Alberta’s laboratory services have endured under-resourcing, destabilization and budgetary uncertainty as well as seven consecutive years of wage freezes. The prospect of a unified, coordinated and centralized public lab system promised a much-needed degree of stability. Instead, AHS announced it would seek proposals for a private takeover of community-based lab services. The contract was eventually awarded to DynaLIFE, though its implementation has been pushed back: APL is still running flat-out after COVID-19 prompted the largest testing operation in Alberta’s history.

The Ernst & Young AHS review initially claimed that outsourcing labs (again) would save Alberta’s healthcare system over $100-million; AHS’s own calculations later revised that figure to potentially as low as $18-million. Whatever the ultimate savings, if any, they will come at great cost to lab workers, patients and communities. As evidenced by Alberta’s past experiences with laboratory privatization and research published in January 2022 by the Parkland Institute, the DynaLIFE deal offers false economies, a smaller and demoralized workforce, a massive infrastructure deficit and a fragmented system with little public accountability. All of these lessons would have to be ignored to consider the further privatization of labs a good idea.

Outside of the lab, corporate profit has also been invited into Alberta’s blood services. In November 2020 a private member’s bill from UCP backbencher Tany Yao enabled the repeal of legislation that had explicitly prevented for-profit blood donation and had enshrined blood and plasma products as public resources, not market commodities. This means private companies can now purchase blood from Albertans, and that “donors” can be financially compensated. While the goal for Alberta—and Canada broadly—should be to secure its blood and plasma supply for the public, the use of for-profit brokers in Alberta enables locally collected blood to be sold to the highest bidder, regardless of country. Yao said he “has faith” that Albertans will continue to voluntarily donate blood, but Canadian Blood Services CEO Graham Sher warned in 2020 that a rapid expansion of the commercial plasma industry “absolutely does have the potential to encroach on the voluntary blood sector.”

The fragmentation of the blood system also presents safety risks: a single, voluntary, closed donation system was implemented with the creation of Canadian Blood Services following the blood contamination scandal of the 1980s, when thousands of Canadians were infected with HIV and hepatitis C from tainted blood and plasma products.

The tragic consequences of profit-driven services have been demonstrated in long-term care in Alberta, where private corporations control one-third of facilities. In a province-wide study conducted by the Parkland Institute just prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, respondents were asked whether their facility had adequate staffing to provide quality care for residents. A significant disparity could be seen across ownership/profit categories: 34 per cent of respondents based in for-profit facilities in Alberta reported they never have adequate staff-to-resident ratios to meet resident needs, compared to just 7 per cent for public facilities. Not-for-profit facilities fell in the middle, at 16 per cent.

In the pandemic context, this correlation between profit status and quality of care has contributed to worse outbreaks and more fatalities in for-profit facilities—glaringly so among the largest corporate chains. Yet rather than take these lessons to heart and reform seniors care services based on evidence, the UCP government rushed to pass legislation that would indemnify private providers against lawsuits by residents and their families. They allocated further funding to expand for-profit facilities at the expense of public care.

Similarly, the UCP government has increased the amount of public funding that government will provide to private home care providers, which further fragments services (offloading care and costs onto families) and removes oversight and accountability.

The most glaring example of how the UCP government’s privatization agenda goes against evidence and reason is the Alberta Surgical Initiative (ASI)—purportedly a response to long waits for elective surgical procedures. The ASI is the ideological descendant of Ralph Klein’s “non-hospital surgical facilities” scheme. Now rebranded as “chartered” facilities, these private, for-profit corporations bid to perform a guaranteed volume of surgeries to be paid for using public dollars.

In March 2020, as COVID-19 was gaining its spiky foothold in Alberta, the UCP government launched the ASI with $500-million to be spent over three years. Only 20 per cent of this money was earmarked to increasing surgical capacity in the public system. While the government pointed to a backlog of surgical procedures generated by COVID-19, the truth is that the ASI was a key part of the UCP agenda prior to the pandemic—the delays caused by hospitals’ reduced capacity merely provided the impetus to double down on private contracts.

Later that year the timeframe for the initiative was moved up. Then, in September 2022, Alberta Health announced even more investment in the ASI, launching a request for proposals to contract a further 2,600 surgeries in Alberta’s South and Central zones.

The goal, as stated in the UCP government’s 2022 throne speech, was to increase the share of privately contracted surgeries from 15 per cent to 30 per cent. But the bigger victory is to cement a shift in how Albertans think about healthcare delivery. Former premier Kenney insisted that the ASI, because it involves public funding, isn’t really privatization. This is a rhetorical smokescreen meant to convince Albertans that delivery doesn’t matter, and that private for-profit enterprise is somehow inherently more efficient than public providers.

Failed experiments in other provinces show privatization doesn’t cut wait times or save money.

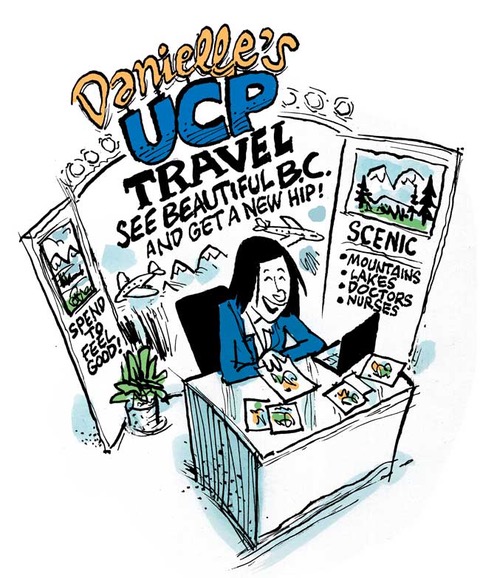

Sadly, multiple studies—and various failed experiments in several provinces—demonstrate that private contracting doesn’t reduce wait times in the long term, doesn’t save money and doesn’t improve patient care. Documents obtained by CTV News in September 2022 indicate that AHS is behind target on its surgical volumes precisely because ASI prioritizes channelling surgeries to private contractors. Meanwhile the UCP government used political pressure to override medical advice and common sense in a bizarre proposal to fly Alberta patients and surgeons to private facilities in BC’s Okanagan region. Documents obtained by the Opposition through FOIP make clear that the UCP government explicitly directed AHS to launch this scheme despite higher costs to the public and bigger risks to patients.

Private surgical initiatives also raise concerns about accountability and transparency: how contracts are awarded, at what cost, with what consequences for citizens. The lobbying of Alberta Health in 2020 by a private corporation that wanted to build an orthopedic surgical hospital in Edmonton appeared to bypass procurement procedures. A recent report on private surgical facilities by BC-based researcher Andrew Longhurst found that unlawful extra-billing, contravening the Canada Health Act, was widespread within similar facilities in that province—yet the UCP government engaged one of those same companies to build and operate a chartered facility here in Alberta.

The contract means a private surgical centre will be built just outside Edmonton on the Enoch First Nation, a project that closely resembles an ill-fated scheme by former PC cabinet minister Lyle Oberg on BC’s Westbank First Nation. That First Nation withdrew from its partnership with Oberg’s company Ad Vitam Health Care when it emerged Oberg couldn’t guarantee the project would be approved by Health Canada.

While initiatives for Indigenous-led healthcare may or may not improve access for Indigenous communities or address systemic racism, the use of First Nations lands by the UCP government is calculated: facilities there are thought by their proponents to be exempt from the tenets of the Canada Health Act. This is a matter the courts may someday have to consider.

Healthcare workers have provided critical care to Albertans under the most trying of circumstances. After three years of pandemic response, with doctors and nurses and lab techs and cleaners and other healthcare staff using ever-dwindling resources to hold back wave after wave of coronavirus, the physical, mental and emotional capacity of healthcare workers is at an all-time low. To address staffing pressures and widespread burnout requires concerted attention to working conditions, and a far-sighted plan for recruitment, training and retention of skilled staff.

Instead the UCP government has turned to short-term, costly fixes that do nothing to address the deep roots of the crisis. To staunch the hemorrhage of nurses from AHS, Alberta Health has relied on private recruiters and temp agencies to cover staffing gaps—at a massive public cost. As of May 2022 over 200 privately contracted nurses and healthcare aides were working in Alberta hospitals and continuing care homes.

While these employees can be paid much more than AHS staff—double, in some cases, according to United Nurses of Alberta—much of that increase only covers agency fees. For nurses in particular, choosing the agency route trades income stability for scheduling flexibility—a steep price to pay for something as basic as predictable time off.

It can, unfortunately, always get worse. Under Jason Kenney, the province turned to expensive, ineffective efforts; new premier Danielle Smith has shifted to promoting conspiracy theories and wild, unsubstantiated claims that AHS “manufactured staffing shortages.”

During the peaks and troughs of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UCP government’s repeated refrain was that they wanted to prevent the healthcare system from being overwhelmed. Their actions, always too little and too late, suggest otherwise. Like a teenager burning dinner so that the parents have to order pizza, the UCP’s response to the health challenges besetting Alberta has been deliberate. Should our public healthcare collapse, it will have been neither accidental nor inevitable: this is a conscious choice by a political party. But the success of the UCP’s efforts hinge on Albertans’ exhaustion and hopelessness.

Albertans have long seen conservative leaders attempt to undermine and reshape public healthcare into a tool of the market. The spectre of private healthcare returns so frequently in Alberta politics that its perpetual resurgence is used to discredit people sounding the warning. “You keep crying wolf,” they say, “but there are no dead sheep here.” This dismissal, however, is misguided: the wolf is hard to spot because it wears sheep’s clothing, and sheep survive in the meadow only because someone keeps raising the alarm, again and again.

Public solutions to the crisis were always possible—and still are. Universal, accessible public healthcare exists because we have fought for it. Let’s keep fighting.

Rebecca Graff-McRae is the research manager at the Parkland Institute and the author of “Misdiagnosis: Privatization and Disruption in Alberta’s Medical Laboratory Services.”

____________________________________________