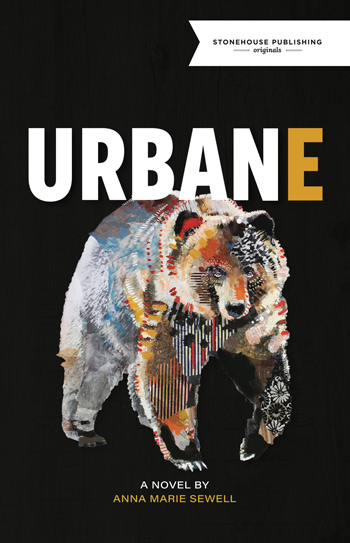

Urbane, Anna Marie Sewell’s sequel to her bestselling debut novel, Humane (2020), continues the exploits of Hazel Lesage, a middle-aged private investigator in Amiskwaciy (a.k.a. Edmonton). Hazel is determined to help people, Indigenous or not, especially when they are poor and neglected. Missy and Frankie, Hazel’s adult daughters, are willful, smart and independent, just like their mother. Sandra, Hazel’s sister, with whom she often butts heads, has raised their nephew Devin after the loss of his parents. The events in Humane have traumatized Devin, and the family, while desperate to help him, haven’t much idea of what to do.

It’s probably not necessary to read Humane first, but I recommend it. Sewell—a performer and the author of two earlier poetry collections—does fill in the gaps, but the complicated plot and relationships become a bit clearer with more exposure. Plus the freshness of Humane is engaging. Learning about Hazel and some of the issues that concern her provides a foundation for the sequel. In particular, Hazel’s confusion and surprise at the shape-shifting dog in Humane likely mirror the reader’s, and those initial reactions can’t be duplicated in Urbane.

The past is the impetus for both novels, although in Urbane the past is Hazel’s personal loss of the family farm in her divorce. Shanaya, Hazel’s best friend, is a lawyer as well as a shape-shifting tiger, and the two set out to try to reclaim the property. On occasion Hazel longs for the wilderness: “The thing is, sometimes I wake up and I just want to see bears. I just want to be where I look out the window and there might be deer, or moose, or an elk. Not junkies.” Cities are a place of disconnection for people, Hazel thinks: “We went from lives in contact with the land to living in cities and abandoning the fields and wondering why our food supply was so messed up.” She isn’t against change, but believes human beings have really bungled things up. The quest to regain the farm leads into a heroic attempt to save a group of young migrant farm workers who are in serious peril.

While Hazel and Shanaya drive around the countryside working the case of the farm and the migrants, aided in most unlikely fashion by Hazel’s ex-husband’s second wife, Devin is employed at a garden centre in the city while trying to figure out what to do with his young life. A third-person narrative filtered through Devin alternates with Hazel’s first-person narrative to develop the subplot of the young man.

One of the many strengths of this novel is the various relationships explored: romantic love, family, friendship and culture. And they are all connected. While the title Urbane suggests an investigation into the urban and the urbane, I think Sewell is continuing what she started with Humane. Of that earlier case, Hazel says: “Anyhow … it’s a long story, full of shapeshifters, murderers and the struggle to find out how to be Humane, if not human”; these concerns of being humane are also at the heart of Urbane.

Hazel is a wonderful character among several wonderful characters. She is thoughtful and mouthy. Only once does she pull a punch, and that’s right at the beginning: “If only I had just punched her in the face. I really wanted to, had balled up my fist as soon as the light dawned. The trouble is I was shocked by the sight of her. And it stopped me.” What propels Hazel forward is her thirst for justice, for herself and others. She thinks she is a mess, a self-professed “asshole.” But she’s the opposite.

Candace Fertile is an instructor of English and creative writing at Camosun College.

_______________________________________

Click here to sign up for our free online newsletter.