by Tom Wayman

Harbour Publishing

2020/$18.95/160 pp.

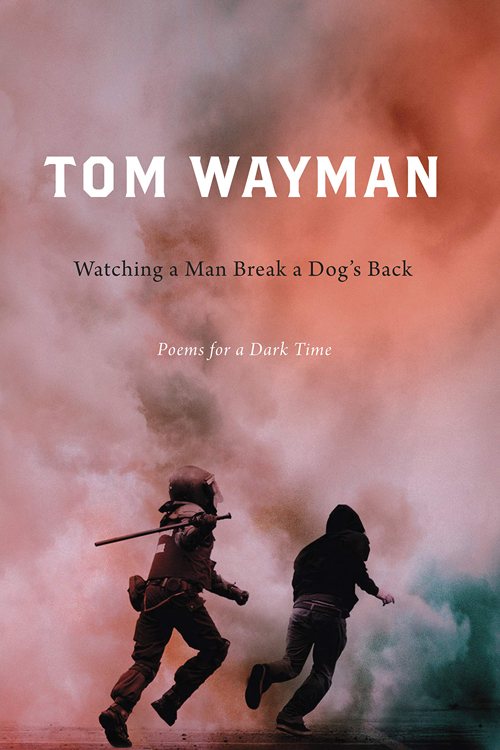

In Tom Wayman’s latest collection, Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back, the long-time poet writes movingly of the natural world and confronts what he sees as “a surging lack of empathy” in today’s society. This concern is prescient and the book’s cover is haunting—a clash between police and protester, the sky hazy and obscured. Words for a dark time, indeed.

Poems like “Complications” and “The Rural as a Locus and Not a Margin” provide insight into Canada’s war-industrial complex and those who deny its existence, and Wayman gathers the crushing waste of war into prophetic utterance: “[n]o one would utter the word/ defeat when our army returned./ Lives had been lost, so victory had to be declared/ and was: we went to war, and after a decade/ of killing people in their own country/ withdrew.” I have read much analysis of Canada’s war in Afghanistan and found little better than what Wayman serves hot in two pithy, profound lines: “[w]hat wasn’t said/ is the memorial.”

At its best, Wayman’s collection carries a deep reverence for the wisdom of growing things and those who gather no capital but live and work with quiet dignity, with “[h]ands swollen and calloused with labour.” At times, however, certain poems lapse into truculence. In one, a poet shouts down an “Aboriginal dancer” for a supposed “rambling attempt at white-shaming.” I have no use for the term “white-shaming,” but I have experienced white fragility—my own and that of others. What did the dancer actually say? Wayman writes that the “[c]herry-picking of historical tragedies and attempts to shame this or that segment of the country’s inhabitants are among the arsenal of approaches aimed at separating Canadians from each other.” Surely truth-telling and the naming of specific historical tragedies are essential to poetry and communal well-being, whether that is Billy-Ray Belcourt writing about a suicide pandemic or Carolyn Forché writing about war crimes—or indeed in this collection when Wayman addresses latent militarism and predatory economics in such fine poems as “O Calgary” and “Wild Swans.”

Theories of social change reside here alongside a lifetime of labour, care, astute observation and the changing of seasons. There is exhaustion too. In “Fifty Years of Stacking Chairs,” Wayman writes, “I imagined a young person would appear/ decades later, take the chair out of my hand:/ [‘]Here let me. You’ve done enough.[’] ” The speaker notes that “people assemble as ever, but with fewer twenty-year-olds/ each year, though the reasons/ to set out chairs are the same: permanent war,/ social injuries committed/ or threatened, a chance to listen.” Wayman has wisdom to offer, certainly—this collection contains as much. But sometimes perhaps he misses that very chance to listen.

Benjamin Hertwig is the author of Slow War (MQUP, 2017).