Polar bears are back at the Calgary Zoo. Their enclosure is different from any offered here in the past. The Wilder Institute/Calgary Zoo announced that the new $11.5-million Taylor Family Foundation Polar Bear Sanctuary constitutes a “world class polar bear habitat,” offering “exceptional” care, with programs providing bears an outlet for “natural behaviours,” “cognitive challenges” and stimulating “play.”

The enclosure exemplifies the zoo’s new approach to polar bears. Interim chief operating officer Jamie Dorgan in July 2023 said that in the past the Calgary Zoo wasn’t “so concerned with animal well-being,” and was “more worried about showing animals to people. Now for us it’s critical, if we’re showing those animals to people, that [the bears] have got everything they need and they’re able to be well-adjusted.” The enclosure aspires to that promise. As part of a larger sampling of Wild Canada habitats, the bears have more than two acres to roam. They have grassy meadows interspersed with trees, rock outcrops, pools of various depths and a wading stream. Hilly topography gives them long views of their surroundings.

Most notably, this “refuge” will keep only naturally orphaned bears. The zoo hopes that by protecting them, they will educate the public while helping save an iconic species threatened by rapid climate change.

But the bears will also draw crowds and business. The Alberta government in 2021 provided $15.5-million for the new “Wild Canada” complex in the expectation that it will raise the zoo’s annual revenues by $13.4-million and increase its annual contribution to the local economy by more than $140-million. Then-Minister of Culture Leela Sharon Aheer said “revitalizing the Canadian Wilds habitat is an important investment that will continue to elevate the zoo as a world-renowned conservation facility.” Those hopes have already been borne out with the zoo’s record-breaking attendance in 2023, when Wild Canada’s opening, and undoubtedly the polar bears themselves, helped draw 1.54 million visitors.

The Calgary Zoo has had polar bears since 1938. Only in the 2000s were bears absent. In their long history in the prairie city, polar bears have lived in very different circumstances. There really isn’t anything new, however, in the zoo’s claims to be meeting the animals’ needs and ensuring their well-being. In the past, zoo officials, zoo experts and Calgary’s media have all reassured visitors that Calgary’s polar bears were happy. And zoo visitors themselves have wanted to believe it too. Perhaps more importantly, each generation of zoo authorities has been confident that the enclosures they built for polar bears were more humane than previous ones.

Not many visitors went to a zoo in the 20th century to taunt or torment animals as they commonly did in earlier times. Anti-cruelty movements in the 19th century confirmed that animals, like humans, suffer pain and emotional distress. Later in the century, experimental animal psychology began revealing high degrees of animal intelligence. Early 20th century bestselling storytellers such as Ernest Thompson Seton, Charles G.D. Roberts and Jack London anthropomorphized animals, attributing to them human-like thinking and feelings. The convergence of animal humanitarianism, psychological studies and popular stories prompted zoo visitors to look differently at captive animals. They wanted to gain insight into the animals’ thinking and emotional state by interpreting their behaviours, and sought reassurance from zoo authorities that the animals weren’t suffering.

Few animals can appear as intelligent, curious, complex in behaviour and happy in captivity as polar bears. William T. Hornaday in the 1920s, drawing from his experience at the New York Zoological Park—one of the largest zoos in the world—said bears were the most popular of zoo animals, after chimpanzees and apes, because of their facial expressions, vocalizations and complex body comportments. Highly intelligent, a bear would constantly change its repertoire of behaviours. Given the opportunity, it interacted with visitors, often to solicit food treats. A bear also ingeniously exploited its enclosures and manipulated novel objects introduced to them. It typically, ceaselessly, sought a means of escape. Famously, Barbara and Sam, two polar bears at the London Zoo, did exactly that in the early 20th century.

Each generation is confident their enclosures are more humane than previous ones.

Calgarians gained first-hand experience with polar bears early in the city’s history. They saw them in 1910 when the German showman Herr Albers showcased his six trained polar bears at the Victoria Park Grandstand. The crowds loved it when Albers had a large water basin rolled onto the stage and prompted the bears, one after another, to jump in to cool off.

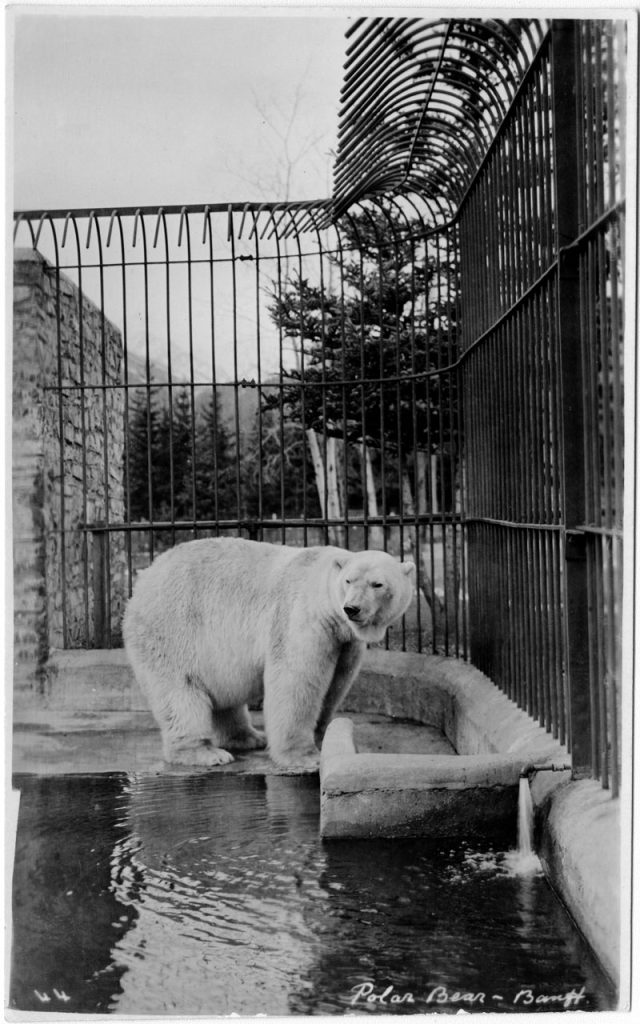

But it was at the zoo in Banff that city folk really got to know polar bears. Canada’s Parks Department traded some mountain goats to the London Zoo to bring two bears to Banff in 1914. From the start, Banff visitors wanted to see these bears, clearly out of place, happy in their new mountain home. When one of them was holed up in his “capacious” den, a reporter stated that “at first sight [he] would appear a most forlorn creature, facing the north, with his head wagging from side to side…. But wait awhile and see him dive into the swimming pool, turning somersaults and playing with an old whiskey keg, and then decide whether after all captivity to him is so irksome.”

When the Banff bears died, after the First World War, they were replaced by cubs, one from the western Arctic, not living long, and another in 1922 from Chestermere Inlet on Hudson Bay. Calgarians got to know the latter, Buddy. Buddy grew up at the zoo learning clownish behaviours conditioned by visitors tossing him peanuts and other treats. Buddy’s complex behaviours generally reassured visitors that he was happy. Young Buddy likely played to experience happiness. But at other times his hyperactivity surely owed to his auditory and visual overstimulation, as well as the anxiety he experienced with throngs of visitors pressed nearby. With keen olfactory senses, Buddy could likely smell each visitor around his enclosure—their perfume, body odours, even the scent of hotdogs on their breath. Since many visitors tossed him treats, Buddy behaved to please people, yet was perpetually uncertain about inconsistent rewards. That most of his behaviours were interpreted as expressing happiness is hardly surprising. Animal humanities scholar Erica Fudge believes that humans want to see captive animals as happy because that makes us happy too.

As years went by, Buddy slowed down. He exhibited behaviours typical of polar bears aging in captivity. The utter monotony of the enclosures drives them to repetitively pace, chew the bars, or swim back and forth in their pools. Bears are most susceptible to boredom, defined by Dutch captive-bear expert G.M. van Keulen-Kromhout as a “disharmony between the natural, internal experience of time and the objective period of time” passed in an enclosure. A bored bear invariably exhibits one or two forms of “neurotic tics.” In 1930 a reporter wrote that Buddy “keeps walking back and forth from the stone house to the iron bars of his cage. The manner in which he swings his hind legs and turns up his flat, hairy paws reminds one of a comedy in the movies.” However comical it all seemed, Buddy still stopped to “entertain his admirers” and beg treats by “sitting on his haunches in front of the bars.”

Calgarians should have questioned why their zoo suddenly deemed the old cages inhumane.

In 1938, shortly after the park closed its zoo, the 16-year-old Buddy was moved to Calgary. By this point, Banff park planners felt that public sentiment was changing, at least among visitors to a “wilderness” park. Visitors wanted to drive slowly in cars to see animals in nature. They didn’t want to see “the confinement of animals in small spaces,” as Banff’s own town advisory council concluded. But the Parks Department had found it nearly impossible to find a zoo to take Buddy. Few could afford to accommodate the 1,000-pound animal. Buddy’s diet was enormous. And he needed a pool. Calgary’s Zoological Society, however, rushed to add a polar bear to its collection. The cage in Banff was disassembled and rebuilt in Calgary. A pool was hastily constructed. Calgary’s Arctic Oil Company paid for Buddy’s feeding in his new “palace.”

In Calgary, Buddy initially remained listless and morose in his cage. The Herald reported that the “glum” bear stayed in his den, much to the disappointment of visitors, but reassured readers that the animal at least rallied at feeding time. When Buddy glimpsed zookeeper Tom Baines coming with a bucket of fish, “he almost tore the cage down to get to them.” Even animal cruelty advocates found evidence that Buddy was happy. “Aunt Marian,” writing a weekly newspaper column for the city’s Junior Humane Society, asked her young readers: “Have you wondered, as I often have, why the polar bear swings his head from side to side as he walks?” She explained she’d learned from authorities that the bear’s behaviour derived “from training his eyes to look for fish in the icy waters of his native land.”

Other zoo officials reassured Calgarians that their captive polar bear was content, even in a cramped, barred cement enclosure and enduring Calgary’s hot summer temperatures. The Herald reported that in Oakland, the Animal Shelter League had raised concerns about Wrangel, a listless and apparently unhappy polar bear at the zoo in 1930. The zoo appointed five veterinarians to look him over; they checked his blood pressure, took his temperature, listened to his lungs. These experts concluded that Wrangel was “not sick or mistreated, but treated too well.” Discovering the bear suffering from eczema, they simply removed all meat from his diet. More reassuring were London Zoo authorities, who, in Calgary’s wire service news reports, stated, “Polar bears in captivity enjoy the heat of summer almost more than the other animals.” The Colorado Springs zoo director similarly claimed “the polar bear does not like cold weather. The warmer it is, the better the polar bear likes it if they have plenty of water.”

In 1949 the Calgary Zoo expanded its enclosure, as the one built in 1938 now seemed too small. With support from a local bridge-building firm, the zoo constructed a 40×40-foot barred cage (basically double the minimum regulated size of a two-car garage in Calgary now). The bear moving into it had a “palatial cage and swimming pool all of his own,” and the Herald reported him “happily splashing in his new pool.”

in 1938 when the Calgary Zoo acquired its first polar bear–16 year-old, 1000 pound Buddy–from the Banff Zoo, visitors consistently found evidence to reassure themselves that the cramped cage humanely imprisoned this animal.

But how were the bears faring, really? Buddy lived only a year in Calgary before dying of pneumonia. Sonya, his intended mate from the Chicago Zoo, lived less than a year, after she “simply lolled about, listless and panting” in the bear cage. After her death, another bear arrived as a cub: Carmichael. Though female, Carmichael was named after radio comedian Jack Benny’s fictional pet polar bear. Carmichael died in Calgary after seven years from a lung infection. Within a year she was replaced by a male, Carmichael II, a cub that lived until the 1970s (so long that one Calgarian remembered him pacing constantly to the point that “he wore grooves back and forth and at the turning points” of his cage). Carmichael II survived other bears introduced to his cage, including Mary Livingston, a cub that lived only three years.

If current measures had been used at the time to rate the Calgary Zoo’s care for polar bears, it would have failed on most counts. The animals were beset with stereotypies (repetitive behaviours), they only inconsistently reproduced, many deteriorated in physical condition, and they often didn’t exhibit “ecologically valid behaviour” (i.e., they didn’t act like polar bears naturally do). Zoo authorities, Calgary media and the public itself, however, interpreted these bears’ physical condition and behaviours positively. Even into adulthood, Carmichael II was deemed the “Calgary Zoo’s polar bear clown.” He was apparently happy to share space with Mary when she, at four months old, was introduced to his cramped space. When photographed splashing around a hole in their frozen pool in December 1958, the Herald saw “Icy Fun for Polar Bears” at the zoo.

Similarly reassuring the public, the zoo published visitor guides showing an early photo of Carmichael II, still a cub, standing on his hind legs “in a playful mood.” Years later, another photo showed the adult bear standing up to receive food at the end of a long pole over his cage bars. The cutline still read that he was “in a playful mood.” One guide stated that polar bears “are more easily acclimatized to our varying seasons than are the tropical animals,” while “they thrive in Calgary’s moderate climate.”

The Calgary Zoo has always counted on the support of local newspapers to promote visits, most of the coverage confirming the happiness of its polar bears. The Herald ran a photo of an apparently smiling Carmichael II in July 1956, describing him as a “hot weather animal.” When the bear apparently didn’t enjoy the warm April of 1970, he still found “consolation in the still chilly concrete floor and iron bars of his cage.” Numerous newspaper photos show the bear chewing his bars. One that ran in the Herald in February 1951 shows Carmichael II gnawing on his bars, apparently saying, “Ah-h-h-h … six weeks more,” in respect to Groundhog Day. Another shows Carmichael in 1963 doing the same thing: “Zookeepers say polar bears, who are as tough as nails in their native environment, like to keep their teeth in condition by chewing on hard objects.” When another bar-chewing bear was photographed in 1965, the Herald mused whether the animal was “trying to gnaw his way out, or he has a toothache…. Or perhaps he just likes the taste of iron bars?”

Almost any evidence was used to show the bears enjoying their cramped cage or their monotonous diet. Carmichael II was pictured enjoying his “turkey dinner” at Christmas 1963 when a zookeeper was feeding him a handful of “juicy pieces of meat.” Candy, another bear, splashing water from her pool toward a photographer in 1968, seemed to say, “Come on in, the water’s fine.” Yet another bear was later photographed “shooting the curl” as the zoo’s resident “surfing polar bear.” The bear “hangs ten on the biggest wave he can muster up within the confines of his pool,” a newspaper said. During a heat wave in 1971, another photographed bear gripped the bars of his enclosure while floating in his pool, his enclosure deemed Calgary’s “Polar Bear Hilton.” In June 1972 a photo of two bears wrestling each other in their pool said it all: “Play-Time,” the cutline read. “Though they’re far south of their arctic home, these inmates of the Calgary Zoo seem to be enjoying life in the city’s warmer climate.”

Zoos changed course in the 1970s, aiming to offer animals habitat instead of cages. The enclosures now offered more space for animals and naturalistic features. In the blueprint planning, these spaces met the needs of visitors as much as animals. Their layouts obscured fencing by hiding it in shrubs and behind screens of trees; visitors on winding paths could pass these enclosures and feel as though they were among the animals rather than separated from them by bars.

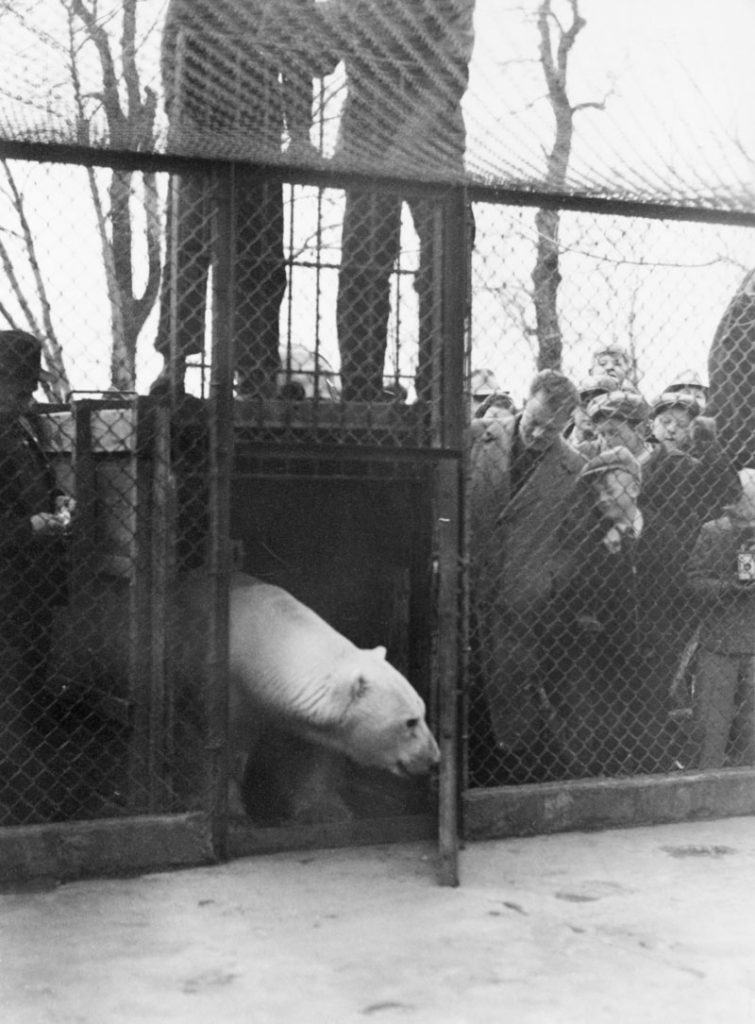

But Calgarians really should have questioned just why the Calgary Zoo in the 1970s suddenly deemed the old and “unsightly” bear cages to be inhumane and was now raising money to build new ones. To help pay for a new polar bear enclosure, the zoo launched its “ban the bars” campaign in 1972 to “remove the last vestiges of a now-frowned-upon part of its history.” A news photo shows the zoo’s director using a welding torch to cut the bars of the old polar bear cage.

Many Calgarians will remember the “polar bear complex” that opened in 1973. Calgary would now serve as a refuge for a species threatened in the destructive circumpolar bear pelt and trophy hunt. Offering more space, the enclosure would also accommodate more bears—its aim being to make Calgary’s collection one of the largest in North America. The enclosure offered unprecedented ways for visitors to view the animals through windows, overhead galleries, even from underneath the bears’ pool. The windows allowed visitors to stand “nose-to-nose” with the bears—an experience touted as “the first of its kind in the world.” With their new “room with a view,” animals inside would “live a bit of the ‘good life’ in more spacious surroundings without bars,” as the Herald reported. Especially when bears were underwater, visitors would get “a clear view of their submarine tricks as they plunge from dry dens and exercise areas above.” All this would be “heartening… to zoogoers used to seeing the same animals do little but pace back and forth out of sheer boredom in small, square iron cages.”

Visitors were indeed enthralled. “Those bars and cramped quarters were, I thought, degrading,” a Calgarian wrote to the Herald, “but with that beautifully designed complex completed, the animals can enjoy more natural and spacious living. Hurray for the people of Calgary.”

But visitors had to stretch their imaginations to see the bears happy in the enclosure, really a big bowl of cement with all its surfaces painted to simulate Arctic ice. A Herald editor said that one bear, likely bored and lying prostrate across a cement barrier—the enclosure was all cement—was having a “poolside snooze.” Here was “one Calgarian [that] didn’t have to go to Hawaii to lie outside by the pool.” Another bear was later photographed “at play” in the basin pool, affirming that “Some folks travel as far as Hawaii or Florida for a wintertime dip. But this polar bear gets his kicks from an icy frolic in his pool at the Calgary Zoo. Retrieving his [toy] hoop from the brink is not only fun—it also gives him his exercise and

daily bath!”

Despite their larger space, the increased number of bears created overcrowding, and the bears acted aggressively. Initially there were Candy and her female offspring, Snowball, and a bear arriving from Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park Zoo in 1971 named (again) “Carmichael.” Soon joining the three bears were two recently acquired from Hudson Bay’s Southampton Island, Sue and Ralph. Two orphaned bears from Cape Dorset then followed. In 1974, in front of horrified children, Carmichael drowned one of the newcomers, Ri, in a shallow pool. The scene was forgotten a little later when a Herald photo showed two of the bears at their pool, “A refreshing dip on a hot day is always one of the great sensual delights for man and beast,” read the caption, but a swim was “double the pleasure” in the polar bear complex, since one of the bears was “licking away at traces of dinner left on his paw. Zoo officials say the bears find their meals finger-licking good.”

But all fun was gone only a year later when, at two years of age, Ralph killed Sue by tearing out her throat. As a dominant male in the enclosure, Ralph became so aggressive towards the females that he was kept separate from them most of the time. In 1979 the zoo had a dentist grind down Ralph’s canine teeth, to give the females a better chance when he attacked them and to teach him “not to be a bully.”

In the long term, the polar bear complex’s “expert” design dearly cost the bears’ psychological well-being. Stereotypic pacing became the norm. The worst affected was Snowball, who repetitively paced or swam in the pool 60 per cent of her waking hours. Snowball made international headlines when the Calgary Zoo tried putting her on Prozac before her death in 1997. The zoo’s last bear, Misty, aged 24, died in 1999.

Given its poor planning, and apart from a couple of loaned cubs in 2005, the Calgary Zoo’s polar bear complex remained empty throughout that decade. The zoo announced in 2005 a new enclosure in the works, “something new and modern that is going to position the organization to go into the next millennium with a huge added attraction to the city.” As part of its “Arctic Shores” section (to also include beluga whales), and to provide a refuge for polar bears in the context of climate change, the new enclosure promised a large and deep aquatic “facility” in which bears could catch live fish. Projected to be 10 times the size of the polar bear complex, this enclosure would offer an ice cave, refrigerated rocks for the bears to walk on, and a hill high enough that they could see Memorial Drive. A bridge would allow visitors above to watch the bears below.

But many Calgarians remembered the polar bear complex. Zoowatch, doing an independent survey in 2006, found that 71 per cent of Calgarians thought the best way to learn about polar bears was in the wild, and 58 per cent didn’t want to see them return to the city. The zoo dismissed the survey as biased, but lawn signs popped up across Calgary protesting polar bears coming to the zoo’s Arctic Shores. Petitions reached City Hall. A Zoowatch-funded billboard on Memorial Drive decried the zoo’s plan to have polar bears and belugas swimming in the city. By 2013, citing rising costs, the zoo shelved immediate plans for the reintroduction, but promised the bears’ return in its “Twenty-Year Planning.”

Today the Calgary Zoo is reassuring Calgarians that its new polar bear enclosure is planned carefully around current animal science. The problem, however, is that bear science only partially translates into “zoo biology,” the latter factoring in human and non-human animals and their interactions, balancing the necessary modifications of artificial environments to please visitors and animals alike. Fundamentally, enclosure design cannot anticipate an animal’s psychology, since an animal’s mental worldview and emotions can never be known conclusively. More to the point, can humans even relate to an animal’s emotions, whatever they are? Does a bear feel happiness like humans do?

There was little foresight in 1938 when the zoo acquired its first polar bear. The zoo and its visitors consistently found evidence to reassure themselves that the cramped cage, expanded in 1949, humanely imprisoned these animals. In 1973 the zoo unveiled the polar bear complex as an effective alternative. The complex still casts a dark shadow on the history of polar bears in Calgary. The 2004 design, never realized, offered a refuge space that other experts promised would keep bears and their human visitors happy. (What bear wouldn’t feel content looking at traffic jams on Memorial Drive?) Whatever passions, hubris, civic pride and science have gone into hosting polar bears in this prairie city—and whatever the best of intentions of the zoo and its visitors—polar bears still find themselves in a foreign habitat and alienated from their own natural history.

Ultimately the Calgary Zoo is accountable for the health, both physical and mental, of these Arctic creatures. Beyond what they now learn from zoo authorities about the welfare of these animals, Calgarians, as zoo visitors, should be as circumspect about their own perceptions of the bears in their newer, larger, “world class” enclosure.

George Colpitts is an environmental historian at the University of Calgary interested in human encounters with the wild world.

____________________________________________