Alberta’s renewable power industry was purring pleasantly along on the evening of August 1, 2023, and no wonder: our province was home to 90 per cent of Canada’s new wind and solar projects. But it proved to be a reluctant host. For on August 2 the industry awoke with a start to find itself flailing in the political wind of the UCP government’s if-it-ain’t-broke-break-it parallel reality. Premier Danielle Smith et al. had suddenly announced a seven-month “pause” on all new renewable energy projects. In the interim, the Alberta Utilities Commission was to propose some new guidelines on development. The pause drew sharp rebukes from industry players and clean-energy advocates. According to the Pembina Institute, 53 projects were “abandoned” after the UCP moratorium was announced, putting at risk $33-billion in investments and 24,000 job-years. It turns out that trying to rebottle the green genie can be very expensive.

Fast forward to February 28, 2024: the pause was ended—sort of—as premier Danielle Smith and minister of affordability and utilities Nathan Neudorf outlined some of the regulator’s key findings in a report with the windy title “AUC inquiry into the ongoing economic, orderly and efficient development of electricity generation in Alberta, Module A”, dated January 31, 2024. (Insomniacs can find that on Google; it beats sleeping pills.) A number of conditions would have to be met: for example, protection against losses to the agricultural land base and threats to farming operations would be the number one priority. Rural municipalities were also insisting on being properly consulted on new projects and having a seat at the table when decisions were made by the regulator. And they also wanted assurance that developers would post bonds and agreements to assure reclamation of wind and solar sites when project life was ended. The latter condition is essential in Alberta, where the preferred form of reclamation (think orphan oil and gas wells) is to declare bankruptcy.

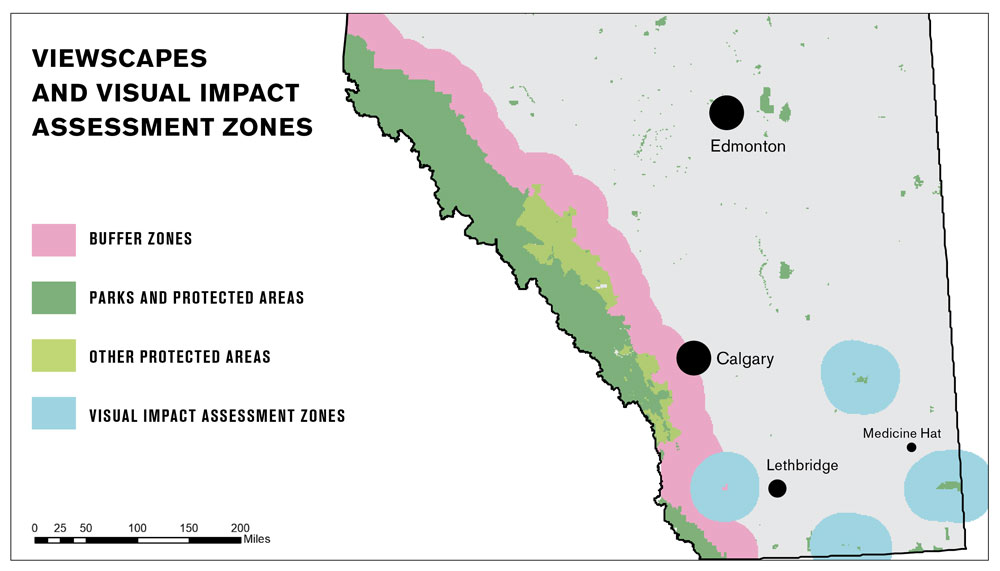

As a former talk-show host, premier Smith knows how to give good phone to soothe any rumbling in the belly of the beast, by which I mean her base, which is mainly rural. “Protecting Alberta’s land,” she said sternly, “is also why we will establish buffer zones of 35 kilometres around protected areas and pristine viewscapes as designated by the province.” In a statement that seemed to single out TransAlta’s Riplinger proposal in Cardston County, which would have sited 47 turbines, each 195 metres tall, close to Waterton National Park, she said: “You cannot build wind turbines the size of the Calgary Tower in front of a UNESCO World Heritage site or on Nose Hill or in your neighbour’s backyard. We have a duty to protect the natural beauty and communities of our province.” Now that is some skookum wawa that should thrill the UCP base.

Was Smith not impressed by TransAlta’s claim that Riplinger could produce enough energy in an average wind year to power 138,000 homes or boil 3,960 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water? TransAlta’s CEO John Kousinioris responded to the new buffer zone in May of 2024 by cancelling the Riplinger project and (cheekily) putting several other green projects on “pause,” citing the buffer zone and a general lack of clarity coming from the Alberta government in his decision.

I can imagine some readers saying “This is all just batshit crazy,” while others, more sanguine, might opine “It’s about bloody time!” The renewable energy industry, however, has been left in confusion, trying to figure out what qualifies as a pristine viewscape. The map released by our government implies that they mainly consider the viewscapes along the mountain front as pristine. Minister Neudorf mentioned a desire to protect “tourist landscapes” as part of the rationale for his government’s decision, but when pressed by media he admitted “there is no universal definition of a pristine viewscape; however, many use that term to refer to areas that are unobstructed natural landscapes.” The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.

The AUC’s opinion echoes the minister, though it prefers the term “valued” viewscape instead of “pristine.” And yet the commission left the door open for excluding other industries in the buffer zone, maintaining that protection of viewscapes should be “industry agnostic and apply equally to all forms of development.” They didn’t swallow Danielle Smith’s Kool-Aid targeting renewables. The AUC also naughtily pointed out that from 2019 to 2021 the largest driver of land loss in Alberta was the “expansion of pipelines and industrial sites,” not solar or wind development.

Perhaps wind turbines would spoil the view of the coal mine.

Full disclosure: I’m a ratepayer in the MD of Pincher Creek No. 9, a founding member of the Livingstone Landowners Group and no fan of the current political regime. I’m worried about climate change, so I support renewable energy. But I’m also one of many people here who think that nine wind farms in this MD are more than enough for one jurisdiction to deal with. You might expect, given this, that I would welcome a more cautious approach on wind power hereabouts. Not so fast. I’ve found that a steady state of paranoia is the prudent way to deal with the ready-shoot-aim policy shifts of Alberta’s right-wing politicians.

The term “pristine viewscape” trips uneasily from a Tory’s lips. There’s nothing too pristine about their beloved oil sands mines, toxic tailings ponds or clear-cut logging operations. Such things elicit a kind of earth-ravished angst that many Albertans don’t care to contemplate—or even look at. So what has happened to Danielle Smith’s sense of the aesthetic? Perhaps some pixie dust from the chemtrails sprayed on her base by the US Department of Defense has expanded her awareness of nature’s grandeur? Does she really care about any scenic splendour that has not already felt the caress of a bulldozer blade or the embrace of a feller-buncher?

So many questions, so few answers.

After all, she heads a government that seems hell-bent on resurrecting a zombie coal mine, the Grassy Mountain project just north of Blairmore, that had multiple stakes driven through its heart by the Alberta Energy Regulator, the federal environment minister and the Alberta Court of Appeal. Yet it staggered back to unholy life on November 16, 2023, when energy minister Brian Jean suggested the same AER should take a new gander at Aussie billionaire Gina Rinehart’s favourite dead coal project. By the way, the Grassy Mountain open pit proposal, which includes a “350-tonne load-out bin” and a new railway loading spur next to the Blairmore hospital, is well within Smith’s 35-kilometre buffer zone. Perhaps wind turbines would spoil the view of the mine or fan up too much coal dust in the Crowsnest Pass. Those whirling blades might distract hospital patients from enjoying the lullaby of train whistles and shuttling coal cars being loaded, clang-bang, 24-7.

Further, minister Jean could be feeling nervous about the multi-billion-dollar lawsuit his government is facing from four mining companies after former minister Sonya Savage reinstated the Lougheed coal policy and closed the mountains to new open pit mines in 2022. And worse, Jean’s old political enemy, former premier Jason Kenney, is a senior adviser at Bennett Jones, the firm handling the lawsuit. And lo—that’s the same Jason Kenney who presided over the attempt to overturn the Lougheed coal policy in the first place. “No worries, mate. Just throw Brian Jean on the barbie.”

Good old UCP, still steering Alberta by a broken moral compass. This government suffers from a terminal case of irony deficiency—and from constantly being “hoist by its own petard.”

The new “no-go” zones for renewables include “viewscapes” and “visual impact assessment zones” plus agricultural land. But not all new energy development is banned; the UCP seems to believe coal mines and pipelines are somehow prettier to look at than windmills or solar panels.

Long ago, in a different time and a different world, I wrote: “Each mountain/ its own country/ in the way a country must be/ a state of mind.” I could easily have said there are as many mountain moods as there are mountains. They are that changeable, both welcoming and threatening when you live among nature’s uncompromising cathedrals, these water-towers of the West. When not admiring the constant play of light and cloud-shadow rippling across their ridges, I love to view them from a distance. The Piikani people called them “the backbone of the Earth”; they were known as the “Shining Mountains” to 18th-century fur traders. I can see why their classic profile appears on Alberta’s flag and provincial shield. Something worth protecting, one would assume, and some of us definitely try.

But the shining mountains are no longer the only towering images above southern Alberta’s plains and foothills. White wind turbine towers, some as high as 90 metres from ground to hub, with a rotor diameter of 100+ metres are steadily upstaging the view.

The Municipal District of Pincher Creek was home to Canada’s first commercial wind farm, at Cowley Ridge, in 1993. Its 52 windmills, outlined against the mountain backdrop, predicted how the industry would relate to the “pristine viewscape.” These first latticed towers, some 25 metres high, were replaced in 2017 by a row of 15 turbines measuring 46 metres. According to the US Department of Energy, hub heights of land-based windmills have increased by 83 per cent since 1999. “In 2023,” the department notes, “the average rotor diameter of newly installed wind turbines was over 133.8 meters… longer than a football field, or about as tall as the Great Pyramid of Giza.” The reasons are simple enough: wind shear increases with a gain in height while surface friction (by trees, buildings, grass etc.) is diminished. And the longer the rotor blades, the more energy they capture for the turbine.

In two decades, the mountainous scene west of Fort Macleod and Pincher Creek, from Chief Mountain north to Crowsnest Mountain, and from the Porcupine Hills west to the Livingstone Range, that thrilled many a first-time visitor to this place, has been rapidly transformed by wind turbines as this part of Alberta became the centre of wind farm development. Most locals supported the industry. In Alberta’s free-wheeling energy market, there’s a lot of money to be made by vandalizing the view, both for the developer and for the landowner. I could not obtain information on current leases, but in 2017 Evan Wilson of the former Canadian Wind Energy Association told the Calgary Herald that “every 150 MW of new wind power represents $17-million in lease payments… over a 20-year period and $31-million in property taxes to municipalities.”

Historically, the Alberta Utilities Commission paid little more than lip service to those citizens or local politicians who objected to the pace of development or to turbine placement. The most glaring example of unregulated growth begins a few kilometres west of Brocket, where huge steel transmission towers and a maze of high-tension power lines frame a tangled view of multiple windmills, their huge blades slicing at the sky. Windmills and transmission lines, due to sheer numbers, have become a man-made geographic feature, a creeping industrialization of the signature Alberta landscape that appears on Alberta’s provincial flag. The effect for a long-time resident is a solastalgic assault on the nervous system, a cognitive dissonance where cherished memory meets current realities.

Of course, most of these space-age marvels are well within Danielle Smith’s buffer zone and are grandfathered-in from her newfound pristine obsession.

When it comes to new wind-power development hereabouts, however, the honeymoon phase is probably over. According to the The Western Producer, a survey conducted in 2006 found 90 per cent of MD residents favoured wind-power development. But as development increased, a new survey in 2017 showed only 54 per cent were still in favour of more turbines. The industry is looking farther afield for new sites these days. The local development officer, Laura McKinnon, told me there has not been a new wind-power application here for three years. Right now the biggest windfarm in Alberta so far is the Buffalo Plains facility, and it’s well out on the prairies of Vulcan County. Personally, I think the industry would be more popular here if it had just showed more sensitivity in siting its turbines, sacrificing some height in return for more social acceptance and goodwill.

A “pristine” pumpjack near Longview, in the foothills of the Rockies, on the Cowboy Trail (Highway 22) south of Calgary.

Criticizing wind power during this disastrous era of climate change is like criticizing mom’s pumpkin pie. Calgary politicians have touted the fact that the CTrains run on wind power. But the electrons from wind-powered or gas-powered turbines flow through the same wire. Since urban residences and industry use most of the electricity, why not put the windmills closer to main consumers, thus cleverly reducing material expense and line loss of power over long transmission distances. Why not insist on solar panels on city rooftops, which is becoming the norm in Europe? Could it be that city folks might find such installations (especially wind turbines) not to their liking if they were forced to look at them day and night, while watching their electrical bills increase despite all the new infrastructure that comes with new power generation?

While two feuding entities, the Green Genie and Youseepee No-vax, are cudgelling their wits for a social media assault on yours truly, let us slip into a handy thicket of etymology. The word “pristine” derives from the Latin pristinus, meaning “former,” according to the Canadian Oxford Dictionary. Over time the meaning evolved from “ancient, primitive” to “1: in its original condition; 2: fresh and clean, as if new; and 3: unspoiled (pristine wilderness).”

We’re all familiar with current usages, as in “used F-150 in pristine condition,” “pristine bottled water,” “pristine starter-castle for the millionaire handyman”—whatever. None of these meanings apply to either the viewscape of the Rocky Mountains or the condition of its myriad peaks and river valleys. You may hike up to see the untouched marvels of Window Mountain Lake north of Coleman, for example, but don’t drink the water unless you are hankering for a dram of polycyclic aromatic compounds found in the coal dust blown into it from Teck Resources coal mines just across the Great Divide.

You could also argue, based on several factors, that there is no pristine wilderness to be had in these latitudes, let alone a pristine viewscape.

The view west of the windmills, as I write this, may not be pristine, but as the dwarf birch turns crimson and the aspen leaves go to yellow, the foothills and mountainsides are a watercolour artist’s dream, and that includes the battalions of round hay bales, the yellow fields of canola, the still-green grasslands topping high foothills and the distant ranch-houses and barns backed by the blue-grey walls of the mountain backdrop with endless cerulean skies above. There is a word for a view like this that stirs our heartsprings with love for our native place: sublime. Sublimity is what meets the eye when you leave the wind turbines behind.

As a young park warden in Jasper, I once endured a lecture by a Canadian Forest Service officer who liked clear-cut logging and summed it up: “I love to see the hand of man upon the land.” You can see the hand of man at work in the Alberta Forest Reserve just about anywhere you care to look. It’s there in the roads, in thousands of kilometres of seismic lines, in deeply eroded ATV trails, in clogged-up trout streams, logging clear-cuts and abandoned coal mines and slack piles. There are also pipeline rights-of-way, gas flare stacks and transmission lines criss-crossing and scarring the mountains. Even the tree cover today has greatly increased from what it was before European contact, the result of billions of dollars spent on wildfire control to preserve wood fibre for loggers, or in the case of national parks, to protect the scenery. That accounts for the massive fuel loads that feed today’s forest fires.

But in truth, the hand of man cannot be avoided. Even before European contact, the hand of man was at work doing cultural burning to improve the range for deer, elk and bison, to encourage food and medicinal plant growth and to keep some of the trees in check. Historical photos taken by the early surveyors in places like Waterton National Park show a less forested landscape far different from today—at least before the Kenow wildfire of 2017, that is.

Writing in the anthropology magazine Sapiens, Claudia Geib cites the work of geographer William Denevan, who speaks of the “pristine myth”—the belief that all of nature was once a sparsely populated wilderness where humans had little or no influence. She quotes Kawika Winter, an Indigenous biocultural ecologist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa who says: “I loathe that word pristine. There have been no pristine systems on this planet for thousands of years.” Such scholars are part of a growing consensus against the old tenets of “fortress conservation”—the Eurocentric notion that “pristine wilderness” can only be protected by excluding human beings, particularly Indigenous people, from within its boundaries.

What we describe as a pristine viewscape is a kind of political mirage.

In Canada, First Nations people were pushed outside the boundaries of our national parks when the parks were founded. Recently Parks Canada has been striving to undo some of the harm by reaching out to Indigenous people and involving them in programs such as the reintroduction of bison into Banff National Park. That effort was marked in October 2024 by sponsoring a ceremonial bison hunt by members of the park’s Indigenous Advisory Council in which eight bison were to be “harvested” and used by First Nations members.

The Parks effort is a tentative move towards a conservation approach that includes humans as part of the landscape and biodiversity that ecologists are striving to protect. Danielle Smith, whose former claims to Cherokee ancestry qualify as “pretendian,” should stop pretending that coal mines and pipelines are somehow prettier to look at than windmills and solar panels. I doubt the public will be convinced by this petrostate gaslighting of pristine viewscapes, distorting the term “pristine” as a means of simply slowing the inevitable rise of renewables in favour of the fossil fuel lobby. It’s a fallacy that Alberta can have both unspoiled natural beauty and unchained industrial development at the same time in the same landscape—everybody going everywhere doing everything all the time.

The oil well access roads, gas wells and clear-cuts that scar Alberta’s east slope are not visible at a distance of 35 kilometres. In fact, what we describe as a pristine viewscape is a kind of political mirage. The concept that mountains are pristine landscapes is a myth. Yet the ranges of mountains on Alberta’s western horizon are sublimely beautiful. They still inspire awe, and I hope that someday, for all Albertans, they will inspire respect for the forests, the peaks and the rivers that lie behind that famous skyline.

Sid Marty is the inaugural winner of the Al and Eurithe Purdy Poetry Prize for Oldman’s River: New and Collected Poems (NeWest Press, 2023).

____________________________________________

Support independent local media. Please click to subscribe.

Read more from the archive “Where to Put a Solar Farm” November 2023.