When Captain John Palliser’s mid-19th-century expedition mapped out western Canada for European settlement, southeastern Alberta was a stark landscape. Drought had gripped the area. The parched shortgrass prairie, dotted with cactus and sagebrush and the occasional cottonwood grove along the rivers, appeared ill-suited for agriculture.

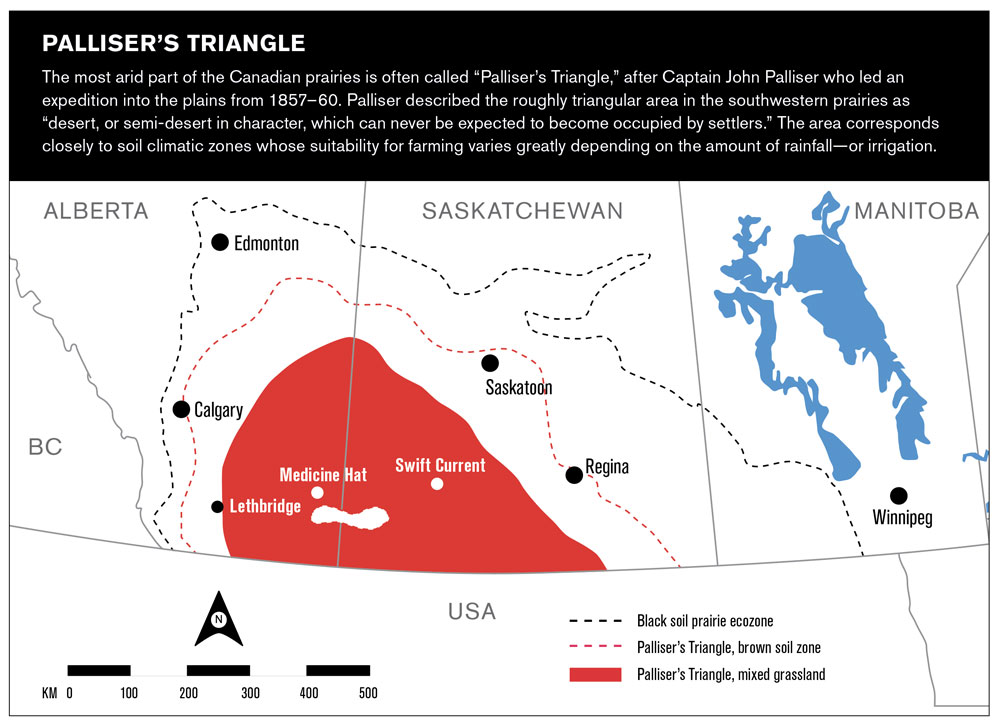

Today the region, encompassing much of the South Saskatchewan River basin, is known as Palliser’s Triangle. It runs roughly from its westernmost point near Cardston, north to the confluence of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan rivers near Oyen, before dipping south to Swift Current, Saskatchewan. And it has a lot of agriculture. This is because the drought that Palliser experienced abated and the region bloomed, as did settlers’ hopes of cultivating crops in the area. Palliser’s report, the first major survey of southeastern Alberta, was dismissed as pessimistic.

That change of perspective was just the first in a cycle in Alberta over the past 125 years, pushed along by dry years and wet years. People in Palliser’s Triangle have regularly had to manage drought or flooding, trying to smooth out the peaks and valleys of water supply. And for over a century now, the solution to flood and drought alike in the region has always been the same—build more irrigation infrastructure.

The Canadian Pacific Railway, having acquired much of the land in Palliser’s Triangle as part of a deal to build a transnational rail line, saw the potential to bring water to lands thought too barren to cultivate for food. It developed the province’s first large irrigation system, hoping to maximize its capacity to ship agricultural products east and transport European settlers and goods west. The CPR system began in 1903 with the construction of a weir at Calgary to divert water from the Bow River to the Chestermere Reservoir. The Bassano Dam, built in 1910, and an extensive network of canals allowed thousands more acres to be irrigated. Southern Alberta soon had one of the most extensive irrigation networks on the continent.

The CPR wasn’t wrong. The combination of a hot, dry climate and available water transformed the region. But today many Albertans are questioning whether further expansion of irrigation infrastructure is a good idea.

The first significant pushback to building more irrigation infrastructure in Alberta came from opponents of the Oldman Dam. Spurred by the 1984 drought in southern Alberta, Premier Peter Lougheed had commissioned a dam at the confluence of the Oldman and the Crowsnest rivers, just north of Pincher Creek. It would create the largest irrigation reservoir in the province. The Piikani Nation, where headgates were to feed a canal network west and north of Lethbridge, fought the project in the courts and on the land. The advocacy group Friends of the Oldman River was launched as well, alarmed that an environmental assessment hadn’t been done for the reservoir and dam.

After a court decision in December 1987 allowed construction of the dam to continue, an emergency debate was held in the legislature. “One of the most justifiable complaints about this project has been that the public—and when we’re talking about $350-million of taxpayers’ money, that means every taxpayer in the province—has not been given ample opportunity to voice their concerns,” said Edmonton-Glengarry MLA John Younie (NDP) in the legislature. “Those objections [are] both economic and environmental.”

Fred Bradley, MLA for Pincher Creek (PC), argued that the future of southern Alberta was at stake. “If we don’t have sufficient storage in the whole South Saskatchewan system, including the Oldman, there’ll be limits to development in the Bow River basin and the Red Deer River basin,” he told the legislature. By this Bradley meant that economic opportunities in those regions could be reduced if Saskatchewan didn’t receive its allotted water under a 1969 interprovincial agreement that dictates how much water must flow across the provincial boundary near Medicine Hat.

In May 1992, after the Oldman Dam was completed, a court-ordered environmental examination recommended that the dam be decommissioned, concluding “the environmental, social and economic costs of the project” exceeded its economic benefits. The Alberta government ignored the report.

Nearly four decades later, the arguments for and against more dams in the South Saskatchewan basin are much the same. People discuss the role of infrastructure in preventing flooding, mitigating drought and creating water security (for both Alberta and our neighbours), and question whether the benefits outweigh the financial and environmental costs.

The reservoir created by the Oldman Dam, for example, hasn’t always ensured water security. In December 2023 the province had 51 active water shortage advisories as drought gripped southern Alberta. In mid-August 2023 the MD of Pincher Creek saw its intake pipe exposed as water levels in the Oldman Reservoir dropped precipitously. The town had to truck drinking water in. That was also the situation for the rural municipality in 2016. Nor has the Oldman Dam always provided security to irrigators whose canals are fed by its reservoir. The initial water allotment for local farmers to begin the 2024 growing season was half the annual average.

But there have been undeniable economic benefits. Since the Oldman Dam opened, the number of irrigated acres in Lethbridge Northern Irrigation District has risen by more than 60 per cent. Irrigation has prompted a boom all along the Highway 3 corridor from Lethbridge to Medicine Hat, now an agri-food hub that processes potatoes and sugar beets grown using irrigation. The corridor includes greenhouses that fill Alberta’s grocery stores with tomatoes and cucumbers, while lentils, beans and peas flow through to international markets. The beef industry is also dependent on irrigation to supply feed crops and power “feedlot alley,” just outside Fort Macleod. Feedlots generate $1.6-billion in farm receipts in Lethbridge County alone.

According to a 2021 report by the Alberta Irrigation Districts Association (AIDA), irrigated acreage collectively represents less than 4.5 per cent of all cultivated land in Alberta’s 13 irrigation districts but produces more than a quarter of the province’s agri-food GDP.

Everyone can agree that the winter of 2023–2024 wasn’t the first time southeastern Alberta has experienced drought. Where people disagree is in what we should do about it.

Earlier this year AIDA released a report on the future of water management in southern Alberta. “The Adaptation Roadmap for the South Saskatchewan River Basin” recommends a multi-option build-out over 20 years involving more infrastructure, including a new dam on the Bow River just south of Brooks, another upstream near Cochrane, a third on the Red Deer River east of that city and a fourth on the upper Belly River, along the western edge of the Kainai Nation, southwest of Lethbridge.

The report also proposes a new off-stream reservoir—one supplied by a canal or pipe—along the Red Deer River south of Oyen to provide irrigation to the Special Areas, three sparsely populated municipalities atop Palliser’s Triangle. The Special Areas were constituted by the province in response to the mass abandonment of the area during the 1930s Dustbowl, and they have remained under provincial governance ever since. Irrigation could transform the region.

The AIDA report is currently being evaluated by the province. Budget 2023 allocated $5-million to study the feasibility of the Eyremore Dam near Brooks, with a report due in spring 2025.

Richard Phillips, general manager of the Bow River Irrigation District, is likewise bullish on building more infrastructure. He says AIDA’s report balances the needs of southern Alberta’s irrigators against those of municipalities while creating more resilience against not only water-supply variations consistent with historical trends but also those predicted by climate change modelling.

Phillips is also the chair of Irrigating Alberta, a consortium of 10 irrigation districts set up to manage the nearly $1-billion that has been allocated to the Alberta Irrigation Modernization (AIM) program. AIM, announced in 2021, is the province’s largest-ever one-time investment in irrigation. The districts themselves are contributing $163-million. More than $407-million will come from the Canada Infrastructure Bank, with the province contributing the remaining $245-million. The 56 projects covered under AIM—including four new off-stream reservoirs—have the potential to increase Alberta’s irrigated area by 84,000 hectares.

Phillips says demand is high for expanding irrigation, but he argues new infrastructure won’t lead to more water being used. In the past, “expansion of irrigation districts has been based on [creating] efficiencies …both on-farm improvements and district improvements,” says Phillips. “We’ve more than doubled the irrigated area since the 1970s but we truly don’t use any more water than we did then.”

In 1976 southern Alberta’s 320,000 hectares of irrigated land was using 2.1 billion m2 of water annually. As of 2022 some 600,000 hectares in Alberta were being irrigated using 2 billion m2 of water. A 2015 report prepared for irrigators, “Economic Value of Irrigation in Alberta,” says water efficiency in Alberta almost doubled from 1965 to 2010, largely through the use of more-precise irrigation systems.

In 1976 southern Alberta’s 320,000 hectares of irrigated land was using 2.1 billion m2 of water annually. As of 2022 some 600,000 hectares in Alberta were being irrigated using 2 billion m2 of water. A 2015 report prepared for irrigators, “Economic Value of Irrigation in Alberta,” says water efficiency in Alberta almost doubled from 1965 to 2010, largely through the use of more-precise irrigation systems.

Now, much of the AIM funding will be allocated to converting open canals to pipelines. This is projected to reduce the estimated 10 per cent of a southern Alberta canal’s water that is currently lost to evaporation.

But water needs vary year to year. A flash drought in 2017 and a prolonged one across western Canada in 2021 saw irrigation districts divert more water than was typical. In wet years such as 2010 through 2015, districts diverted far less. So new infrastructure in Alberta would be about “taking a long-term view… to improve water management for both wet extremes and dry extremes and everything in between,” says Phillips.

Just as with Alberta’s last major drought, which lasted from 2001 into the spring of 2002, the end of 2023 going into 2024 saw an El Niño weather pattern dry up southern Alberta before transitioning into a more neutral pattern. After shrinking alarmingly over the winter, reservoirs in Phillips’s district and the neighbouring Eastern Irrigation District, which draw water from the Bow, were near or above normal levels heading into the growing season.

The “solution” to flood and drought alike has always been the same—build more irrigation infrastructure.

Asked why more infrastructure is needed if Alberta has managed to weather two major droughts in the past quarter century, as well as several extremely dry years, Phillips pointed to the situation faced earlier this year by irrigators who rely on the Oldman system. Going into 2024 the Oldman Dam reservoir was at its second-lowest level ever—drier only in the spring of 2002. The St. Mary Reservoir, whose namesake river feeds into the Oldman downstream of the dam, began this year nearly empty. That situation led to an initial halving of the normal water allotment for St. Mary River Irrigation District farmers, down to eight inches.

“It was a very different picture there,” says Phillips. “This Roadmap (report) isn’t just about the Bow but the whole South Saskatchewan. Many recommendations will improve the Oldman and its tributaries as well.”

And the Roadmap isn’t just about irrigation, says Phillips; it will also develop resilience for flood and drought management. Indeed the report (and nearly every similar one commissioned by the province in the past two decades) says a changing climate is the main reason to build more water infrastructure. “If climate-change models are accurate—and time will tell—we’d expect to see more extreme cycles of flood and drought,” said Phillips. “We’ve seen some pretty crazy things in recent years… Last year we had a good snowpack in the mountains, but it all came down a full month before you would expect to see it. If that continues, it just becomes so much more important to be able to capture the water when it’s available.”

Southeastern Alberta saw record flooding events in 2010 caused by overflowing creeks running off the Cypress Hills. That was only a prelude to the swamping of communities along the Bow and the Elbow rivers in 2013, including downtown Calgary. Says Phillips: “This Roadmap is about adapting to highly variable water supply so we can still have the water we need, regardless of what the weather is looking like.”

Do the benefits outweigh the costs? The Oldman reservoir hasn’t always ensured water security.

But just as they were in the 1980s during construction of the Oldman Dam, the benefits and drawbacks of more dams and reservoirs are open to debate. Biologist Lorne Fitch has been vocal in his opposition to more such infrastructure in Alberta. Fitch worked with Alberta Fish and Wildlife for 35 years before teaching at the University of Calgary and co-founding the riparian stewardship organization Cows and Fish.

“We have seriously overallocated water diversion flows in all of the southern regions,” he says. “As a consequence, many river sections aren’t functioning ecologically anymore. Fish populations have declined, riparian cottonwood communities have suffered, and so the overall impact of irrigation on our rivers has been profoundly negative.”

The Alberta government, despite its enthusiasm for irrigation, doesn’t dispute Fitch’s assessment of the state of wildlife. It announced at the start of a recent and ongoing fisheries engagement process that “native trout populations across the east slopes of Alberta have experienced severe declines in population size and distribution.” A 2018 U of C research paper shows that the population of rainbow trout in the Bow River, for example, shrank by as much as 50 per cent from 2003 to 2013 (Fitch wasn’t one of the study’s authors). This finding was corroborated by Alberta Environment field samples in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

The moratorium the government enacted in 2006 on issuing new water licences in the South Saskatchewan River basin eased some pressure on the environment, says Fitch. But he argues the move didn’t come in time. The amount of water that has already been allocated, he says, can, in a bad year, exceed the supply. “The reality is, the volume that has been licensed may, in some years, exceed the flow in our rivers. The past hasn’t been a good template for the future.”

In 1988 Alberta’s irrigation districts used their full water allocation on the South Saskatchewan River basin. Between that year and the 2006 moratorium, a half-billion more cubic metres of water was allocated from the basin. Collectively Alberta’s irrigation districts today comprise by far the largest water-licence holder in the province.

Moreover, new dams and reservoirs could put pressure on the shortgrass prairie, as the financial allure of cultivating native grasslands might prove too tempting to ignore. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has called the Great Plains “the world’s most endangered ecosystem,” with more than 50 per cent of it converted to crops and much of the rest intensively grazed.

While Fitch isn’t against all developments that impact water—whether irrigation, industrial expansion or resource extraction—he says there doesn’t appear to be much will in Alberta for exploring how much is too much. “We’ve failed to recognize limits and thresholds. The more we cross those lines in the sand, the less resilient we are to changes—and climate change is going to be a big factor, a wrench in the works.” If our environment is already overextended because of our inability to respect ecological limits, he says, “we’re in serious trouble.”

Fitch is critical of the AIDA’s Roadmap report, calling it a product of the “irrigation lobby.” He describes the 19th-century economic theory known as the “Jevons paradox,” whereby technology increases the efficiency of a resource and lowers costs, which in turn further drives demand and ultimately increases overall use of the resource. And, indeed, greater efficiencies haven’t appreciably reduced the overall amount of water used by Alberta irrigators.

In the driest parts of winter 2023–2024, Fitch said the common refrain from farmers, politicians and “the man on the street” was that they hoped more snow and rain would save southern Alberta from drought. “The problem is, hope isn’t a strategy,” he says. “It’s an acquiescence to doing nothing or doing the wrong things. And that’s why we need a better, overarching, objective review of how we manage water.”

A key part of such a review, he explained, would be to help more Albertans understand how logging on the Eastern Slopes of the Rockies is limiting forests’ ability to act as a sponge. Healthy forests slow the release of runoff in times of both drought and flooding. “But the larger the footprint of logging, the greater the runoff…. We’ve subjected the sponge to too much pressure, and the headwaters can’t hold as much anymore. It runs off so much faster, as we’re giving it many more conduits, with roads and cutlines and off-highway vehicle trails.”

Fitch said what he’d like to see is more objective oversight of water management in the province, considering all resource development and its impacts on the environment along with land-use planning. “We have to be a lot smarter about this stuff.”

Fitch isn’t alone in his criticism. Retired agronomist Ross Mackenzie, who worked for Alberta Agriculture for nearly four decades, primarily as a research scientist, believes better on-farm water management and soil-moisture monitoring could make a bigger difference than digging more dams and reservoirs.

“Typically, a cereal crop such as wheat, barley or canola… most years you only need to put on 10 to 13 inches—roughly, depending on precipitation—of irrigation water,” he says. Despite this, he says, irrigation districts commonly provide up to 18 inches per field. Mackenzie remembers working with a farmer in 2023 in the Eastern Irrigation District who was facing the possibility of seeing his 12-inch allocation reduced during a particularly dry spring and early summer. But strict on-farm management proved more could be done with less, he says, with that farm garnering average or above average yields just through improved water use. “He was very careful how much water he put on each field and then reallocated to other fields, particularly silage corn, which was important for the (cattle) feeding operation.”

Mackenzie is critical of Alberta Agriculture for cutting its funding for staff to help irrigation farmers improve such water management techniques. “We have one irrigation extension person that works out of Brooks, but obviously he can’t speak to all farmers across 1.7 million acres of irrigated land. One person can’t do it all.”

Mackenzie also says irrigation districts haven’t picked up the slack left by the province. “Irrigation districts aren’t promoting using good management; they’re just screaming ‘We need more dams, more reservoirs for more water.’ In most years, we’ve had ample water.” A typical year, he notes, sees most districts use 60 per cent of the water available to them, with only some of them nearing 80 per cent of their water licence. “Most irrigation districts in the past 50 years have never used their full allocation. [Then] they have a couple of dry years, low snowpack in the mountains, and they’re saying they need more reservoirs. Most of the time, we don’t,” he says. “We just need to manage our water very carefully and we can do quite nicely.”

In fact, between 1987 and 2020, the average annual water use by irrigation districts comprised 53 per cent of their licences.

The Oldman Reservoir: Spurred by the 1984 drought, Peter Lougheed commissioned a dam at the confluence of the Oldman and the Crowsnest rivers. It remains Alberta’s largest irrigation reservoir.

Looking westward, in December 2023, over a part of the Oldman Reservoir that normally would be under water. Going into 2024 the reservoir was at its second-lowest level ever—drier only in the spring of 2002.

Mackenzie questions the need for the Eyremore Dam, which would be downstream of diversions for the Eastern, Bow River and Western irrigation districts. “All it would do is hold water to make sure (Alberta) is meeting its allocation to Saskatchewan to give them their fair share of water… We have to ask ourselves: for the one time in 20 years or once in 10 years that we’re a little bit short of water, do we really need to be building new dams?”

Mackenzie adds that money is another precious resource in short supply—and that the Eyremore Dam is expected to cost more than $1-billion.

Similarly, Dwayne Rogness, director of the South East Alberta Watershed Alliance (SEAWA), one of province’s 11 watershed planning and advisory councils, says he’d like to see more drought-resistant crop rotations. “Why aren’t we promoting a more drought-tolerant rotation?” he says. “Irrigators want to have row crops in their rotation, but when there’s only so much water, you need to think about adapting and being resilient (at the farm level).”

Rogness was an agricultural fieldman for Lethbridge and Warner counties for over 17 years prior to joining SEAWA, and grew up farming near Lake Diefenbaker in Saskatchewan (which lake was itself created in 1967 by damming the South Saskatchewan and the Qu’Appelle rivers). He says farmers and ranchers across Palliser’s Triangle are already capable of adapting to drought. “We take what the Bow and Oldman rivers give us. We make the best of all those (upstream) situations,” he says. “In all honesty, in the SEAWA watershed, someplace every year is under drought conditions.”

We need more drought-resistant crops. “When there’s only so much water you need to adapt.”

He likewise praises irrigation districts for developing efficiencies in their systems. But he, like Fitch and Mackenzie, doesn’t necessarily share their vision for the future. “Does that mean we add more irrigation?” he says. “I’m not sure.” SEAWA, he adds, is focused not on technological solutions to water shortages, but on natural initiatives, including replanting native species such as cottonwoods, sagebrush and wheatgrass in riparian ecosystems, promoting water conservation, and raising awareness of the role of biodiversity in overall watershed health.

For Richard Phillips, back at the Bow River Irrigation District, the answer is clear. Building more river infrastructure—more dams and reservoirs—will help prevent flooding while making southern Alberta better able to deal with drought. It will help irrigators too, of course, almost as a bonus. And most importantly, he says, building more infrastructure will constitute a recognition that providing a safe water supply to Albertans is a priority. “Districts have demonstrated time and time again that when water is short, people come first,” he says. He cites multiple declarations by districts to that effect. “Irrigation expansion isn’t a threat to water supply for towns, cities, people anywhere.”

Originally from Calgary, Alex McCuaig has been a journalist in southeastern Alberta for more than 15 years, working at the Brooks Bulletin, Medicine Hat News and Western Producer.

____________________________________________

Read more from the archive “More Irrigation, Fewer Farms” June 2021.