Surely we have enough to worry about without the renewed warnings about runaway inflation. But even amid all our various crises, inflation continues to make its way into the headlines: “Canada’s inflation rate hits a three-decade high”; “Is Canada’s inflation rate out of control?”; “Trudeau must act to ease worsening inflation.” We don’t need economists to tell us prices are going up, and we don’t need politicians to tell us we don’t like it. How worried should we be? What are the implications for all of us, especially for people already barely surviving week to week? What’s really causing prices to rise, and what’s to be done?

We are hearing, again, the almost ritualistic argument whenever prices spike that inflation is the inevitable result of generous government spending and that it can be stopped only by governments turning off the taps. Is this true? Is too much government what’s causing the spike in prices, and is cutting it down to size the only solution? Simply, no. Another round of austerity won’t deliver what most Canadians want, won’t address the real causes of inflation, won’t make the essentials more affordable. What it will do is make things worse.

Those seeking smaller government, lower taxes, more private, less public have often played on the generalized fear of inflation to win support for their agenda. After the global financial crisis of 2008, for example, governments quickly cut back on spending precisely because of exaggerated inflation fears. Most experts now agree that was a mistake. Spending was needed to pull us out of the 2008–2009 recession, but austerity trumped recovery, and we continue to pay the price.

The pandemic laid bare the often fatal human costs of decades of austerity, especially for the poorest and most vulnerable. We learned the hard way that our lack of preparedness, our stretched healthcare system, the holes in our safety net and weak labour protections also create huge economic costs. As if these challenges weren’t enough, the recent devastating fires, floods and landslides in BC and on the East Coast underscore how our failure to rise to the challenges of climate change also comes with enormous human and economic costs.

These crises—as crises do—shook us out of our assumptions, led many of us to question the course we’re on and helped us see new possibilities. Summarizing research in France on how the pandemic has affected the public mood, Emanuele Ferragina and Andrew Zola asked: Are we at “the end of austerity as common sense?” Here in Canada, in the US and in Europe, countless headlines heralded a new era: government making a comeback, debt phobia on the wane. Governments of all stripes stepped up in ways we hadn’t seen for decades to attack the virus and help people and businesses survive the economic shocks of COVID-19. For a brief moment, nobody was complaining about deficits and growing debt. The need for active government was undeniable. In fact, in the wake of this resurgent solidarity, governments everywhere were promising to “build back better,” fix what’s broken and seriously tackle climate change and inequality. Progressives could be forgiven for thinking that Overton’s window was shifting.

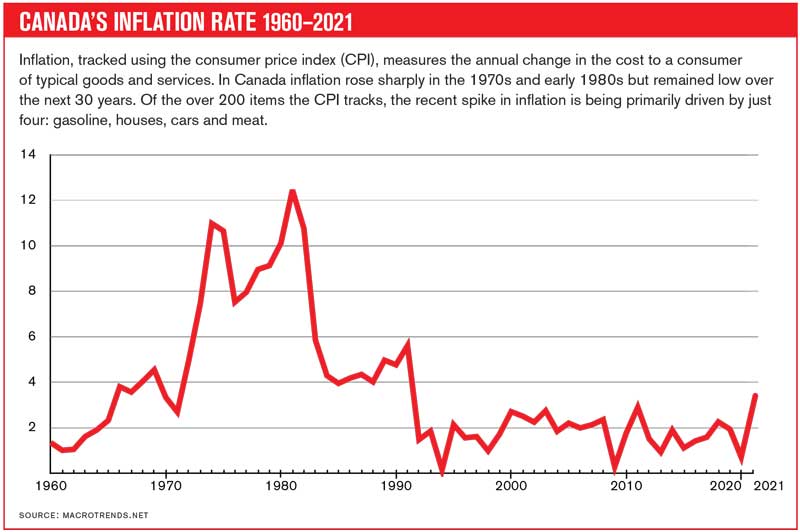

Not so fast. The fiscal hawks may have held their tongues during the worst of the pandemic, but all this has changed. What happened? Prices. In the latter part of 2021, inflation in Canada, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—changes in the cost of about 200 goods and services—spiked more than it had in decades. It has continued to rise, hitting 5.7 per cent in February 2022. While the problem of prices pales against the loss of life, destruction and suffering caused by Putin’s war on Ukraine, the invasion and the sanctions on Russia in response are driving prices even higher, particularly for fuel and food, and adding to the uncertainty about, well, everything. Experts warn that prices haven’t peaked yet and aren’t likely to settle down until mid-2023.

Predictably the austerity rhetoric is also spiking. Once again, inflation is being portrayed much like some dangerous virus with a life of its own that threatens all that we value. And because price increases affect the quality of our lives, inflation phobia is easy politics. Little wonder it has always been poison for a progressive agenda. And now, when we can least afford it, we can fully expect inflation fears will yet again play a central role in our politics, with public spending portrayed as the culprit and some version of austerity as the solution.

The threat of inflation is a key tool in the right-wing arsenal to win support for cuts to public services.

Just how worried should we be? Inflation is, after all, an aberration, just one more miserable feature of a relentless pandemic and a terrible war, and so the worst of it is likely temporary. It was entirely predictable that prices would rise, especially when measured against deflated prices in the pandemic lockdown, when we couldn’t shop or travel. And it was entirely predictable that demand would surge and supply lag as we loosened constraints. COVID-era staff shortages—sick days, self-isolation, reluctance to work in unsafe jobsites—have contributed to bare shelves and unpredictable supply, made worse by unvaccinated truckers being turned away at the border, another reminder that personal choices have public consequences.

And let’s be clear about which prices are rising. As Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives economist David Macdonald showed in a late 2021 analysis, the price spike before the war was largely being driven by just four of the over 200 items in the CPI basket: gas, houses, cars and meat. A fifth—wooden furniture, whose cost is based on lumber prices—came down as quickly as it went up. And none of these increases can in any way be attributed to government spending.

Prices should also be seen in historical context. For years deflation has been a far greater risk than inflation, which has, since 2000, been consistently below the target of 2 per cent. If prices of many of the items in the CPI basket had risen by 2 per cent every year, they would be even higher than they are now. We’ve been living in a low-price world, artificially low, in no small part because workers’ wages haven’t kept pace with productivity growth, and prices haven’t included the environmental costs of our goods.

Agri-food experts at Dalhousie University have shown how higher prices for staples such as meat, dairy and groceries are a result of supply chain kinks caused by both the pandemic and unfavourable weather patterns. As Max Fawcett wrote in the National Observer, “While the supply chain disruptions caused by COVID-19 will get better, the potential impact of climate change will only get worse… because the costs we’ve long externalized, from carbon emissions to plastic pollution, are now going to have to be borne by companies and consumers.”

So, what does this mean for how governments should approach current inflation risks? First, they can’t afford to ignore or minimize the problem. Many households are suffering or are rightfully nervous about what price increases mean for their quality of life. Governments have every reason to act, especially to ensure that the poor and vulnerable are not pushed even deeper into poverty. But, equally, we must not succumb to inflation phobia nor assume the solutions of the past will work now. We need to attack the actual causes of spiking prices and give priority to protecting people who are already struggling. And we really ought to not make things worse.

The first and most important thing governments must do is spend whatever it takes to get us out the other end of this damned relentless pandemic—including fixing the gaping holes in our healthcare system, starting with long-term care, and ensuring vaccine equity at home and for countries that don’t yet have COVID-19 vaccines.

Governments also need now more than ever to ensure that essential services are universally available and affordable. Investment in universal childcare and seniors care will not only address affordability but strengthen the economy and bring more people into the labour market. More-affordable childcare and seniors care would also reduce inflation directly, as the costs of both are included in the CPI.

And while some income supports are indexed to inflation, too many are not, including most provincial tax credits for children and seniors—and, in Alberta as of late 2019, Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH). These must rise as the cost of living rises. The right-wing complaint that “too generous” benefits are the cause of labour shortages not only exaggerates social programs’ “generosity,” it ignores a range of other, more plausible explanations: an aging population and a spike in retirements, a lack of affordable childcare, and most important, low wages and bad working conditions. Is it any wonder that where we find the lowest wages, in accommodation and food services, we also find the biggest “labour shortage”? And if, as research by the Conference Board of Canada suggests, many Canadians have recently taken the opportunity to upgrade or upskill, this is surely a good thing.

Clearly, one of the most important things we can do both to help families struggling with price increases and to address staff shortages in some sectors is to strengthen collective bargaining and labour protections, especially important after decades of relatively stagnant wages.

Certainly some inflation pressures can’t be quickly addressed. Supply chain issues, for example, require a rethink. The endless drive to “just-in-time” manufacturing means products are often assembled from parts sourced all around the world in places where wages are cheap and regulations weak. Whenever slices of a penny can be saved, manufacturing is outsourced. But the longer a supply chain, the easier it is to disrupt, which leads to shortages of goods and higher prices.

A no less important issue is corporate concentration in Canada and the way big firms set prices and pass on higher costs to consumers. Profits of big firms have soared during the pandemic even as CEOs now lead the chorus complaining of “the dangers of inflation.” Our meat industry, for example, is highly concentrated, with only two companies—Cargill and JBS—processing over 80 per cent of Canada’s beef, and profits in the industry have lately hit record highs. Little wonder prices are going up for consumers with little or no gain for ranchers.

We don’t know where prices are heading. We do know that the causes are far more complex than the simple, knee-jerk claims that too much money is sloshing around or too-generous benefits are keeping people home. We don’t fix supply chain bottlenecks or corporate concentration by cutting government spending or, for that matter, by hiking interest rates or otherwise tightening money supply.

In truth, the “there’s too much money” approach to inflation raises more questions than it answers. What determines the supply of money? How is money distributed? Who has it and who does not? What features of our system of production explain changes in supply? Which prices are going up and which down, and what does that tell us about sector-specific problems? What leeway—that is, power—do companies have in setting prices and wages?

To understand inflation and reduce its impact, we have to get at not just money supply but the structural problems in our economy: the impact on prices from corporate concentration and fragile global supply chains; the hidden costs of environmental degradation and climate change; how excessive and untaxed profits contribute to inflation; how treating housing as a commodity for investment and speculation has turned shelter costs into a national crisis; and how decades of eroding bargaining power for workers and reducing benefits have made it much harder for many people to manage price increases. Today, all our systems are undergoing massive change. We’re experiencing the limits of our consumerist society. We’re seeing the inevitable stresses of shifting to a low-carbon economy and the serious consequences of making the shift far too slowly. We’re seeing the huge costs of extreme inequality, of disinvestment in public services, and of treating care and shelter as commodities rather than rights. Inflation must be seen in the context of these structural problems.

What’s needed now is more active government, more public investment, more-engaged civil society.

For too long we’ve been told we can’t afford the society we want, that there’s no alternative to some version of austerity, that mitigating fiscal risks—particularly of runaway inflation—takes precedence even over addressing risks to our collective health and well-being. But we must be clear about what’s most important to us. We can’t entrust the future to the vagaries of the market.

Our approach to inflation should be driven by what best serves public well-being. This means weighing fiscal risks against the risks posed by war, by climate change, by inequality. We might ask too whether a little more inflation is necessarily such a bad thing? The costs of inflation aren’t borne equally. There are winners and losers, though much depends on what costs are rising and how government programs are designed. Generally, people who hold a lot of cash lose. Debtors gain, creditors lose. As always, the poor feel the consequences most sharply. But if we focus on the people already struggling and ensure that all have access to the essentials, is inflation a few points higher than the “preferred rate” of 2 per cent too high a cost for the transformation we need to meet our multiple challenges?

American journalist Ed Kilgore has traced how inflation phobia has killed progressive agendas since the 1970s. When prices spike, people are more receptive to pro-austerity, anti-tax politics. We can’t let that happen now. Canada needs a progressive approach to inflation that takes the issue seriously without slipping into the failed fiscal policies that got us here. If there is too much money sloshing around—and landing in the hands of a very few—a straightforward way to extract it is taxes, specifically higher taxes on the wealthy and on corporate profits, which would also strengthen our collective toolkit to get done what needs doing and contribute to reducing inequality.

We can’t afford to cave in yet again to calls for austerity as the best and only solution to inflation. A return to austerity will most surely yield more human suffering and a weaker economy, will leave us ill prepared for the next pandemic, and will bring the catastrophic consequences of climate change that much closer. What’s needed now is not government withdrawal but more active government, more public investment, more-engaged civil society and a rebalancing of power. People need help to manage the inevitable disruptions—including price increases. We cannot allow inflation phobia to deflect us.

Alex Himelfarb was Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to Cabinet for three prime ministers.